Anton Chekhov characterized his long story (novella, whatever) as "something rather odd and much too original." It does feel distinctly modern now. He wrote it after a journey to Ukraine for his health, rejuvenated by a reacquaintance with the geography of the steppe. I have similar feelings, I think, for the North American Great Plains, the grasslands of eastern Montana and Wyoming and the western Dakotas, which are steppe-like. The story focuses on a young boy, an orphan about 9, who is traveling with his uncle to be placed in a boarding school. It's high summer, hot and sweltering. The uncle has other business in the region and the boy is sent ahead with a group of peasants hauling a wagon train. A priest is also traveling with him. The action is built out of the boy's perceptions of this immense journey and the radical changes in his life. All these characters—a handful of the peasants become familiar to us—are like vivid phantoms flickering in and out of the vision of the boy. Many times he doesn't understand them but we often can even when he is confused. Toward the end he and the wagon train party encounter a giant thunderstorm. Chekhov has a great way of staying inside the boy yet always keeping us aware of the situation outside him too. It alternates between the concrete—the storm is wonderfully done—and the dreamy, as the boy's perceptions are often mixed-up and childlike. We grasp the poignancy of his situation as he will not for years. He's so alone in the world—his uncle accepts the responsibility for him, but he's not cut out to be a family man or father figure (even though he obviously has become the boy's father figure). The story often reminded me in pleasant ways of road trips I've taken across the Great Plains, not just the geography, though that is striking, but the sense of travel as an emotional or even spiritual transition from Point A to Point B. This journey obviously represents a lifetime before-and-after event for the boy no matter what happens next. Somehow Chekhov captures the almost unimaginable hugeness of it.

Delphi Complete Works of Anton Chekhov

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Friday, March 27, 2020

In a Lonely Place (1950)

USA, 94 minutes

Director: Nicholas Ray

Writers: Andrew Solt, Edmund H. North, Dorothy B. Hughes

Photography: Burnett Guffey

Music: George Antheil

Editor: Viola Lawrence

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Gloria Grahame, Carl Benton Reid, Frank Lovejoy, Jeff Donnell, Art Smith, Martha Stewart, James Arness, Billy Gray, Robert Warwick

As much as anything, In a Lonely Place stands as an interesting example—and there aren't that many of them—of a movie adaptation that is as good as the literary property it's based on. What's more, both book and movie stand as innovations in their unique ways, but they are different ways. Director Nicholas Ray and screenwriter Andrew Solt "changed the book" so self-consciously they even made the issue part of the story, which is set in Hollywood and involves a screenwriter, Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart). Compare the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, in which Steele is a mystery novelist. Part of the movie's story is that Steele has been given an adaptation to do and he's told specifically not to change the book.

But changing the book, obviously, is exactly what Ray and Solt did, and not just making Steele a screenwriter instead of a novelist, which is merely cute. In Hughes's short novel, published in 1947, Steele is not only the killer (that's no spoiler, btw, it's front and center as a story element) but in fact he is a serial killer—and Hughes's book looks forward to Jim Thompson's The Killer Inside Me, published in 1952, which takes the conceit even further by making the killer and serial killer also the first-person narrator. But Hughes dreamed hers up first, and as a woman she also brings a compelling view of male rage. In the movie Steele has serious anger management issues that are eating him alive and destroying his life, but he's no killer, let alone psychopath. There is something wrong with Steele in both book and movie, but Ray and Solt took him in a direction that is more realistic, if depressing.

Director: Nicholas Ray

Writers: Andrew Solt, Edmund H. North, Dorothy B. Hughes

Photography: Burnett Guffey

Music: George Antheil

Editor: Viola Lawrence

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Gloria Grahame, Carl Benton Reid, Frank Lovejoy, Jeff Donnell, Art Smith, Martha Stewart, James Arness, Billy Gray, Robert Warwick

As much as anything, In a Lonely Place stands as an interesting example—and there aren't that many of them—of a movie adaptation that is as good as the literary property it's based on. What's more, both book and movie stand as innovations in their unique ways, but they are different ways. Director Nicholas Ray and screenwriter Andrew Solt "changed the book" so self-consciously they even made the issue part of the story, which is set in Hollywood and involves a screenwriter, Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart). Compare the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, in which Steele is a mystery novelist. Part of the movie's story is that Steele has been given an adaptation to do and he's told specifically not to change the book.

But changing the book, obviously, is exactly what Ray and Solt did, and not just making Steele a screenwriter instead of a novelist, which is merely cute. In Hughes's short novel, published in 1947, Steele is not only the killer (that's no spoiler, btw, it's front and center as a story element) but in fact he is a serial killer—and Hughes's book looks forward to Jim Thompson's The Killer Inside Me, published in 1952, which takes the conceit even further by making the killer and serial killer also the first-person narrator. But Hughes dreamed hers up first, and as a woman she also brings a compelling view of male rage. In the movie Steele has serious anger management issues that are eating him alive and destroying his life, but he's no killer, let alone psychopath. There is something wrong with Steele in both book and movie, but Ray and Solt took him in a direction that is more realistic, if depressing.

Monday, March 23, 2020

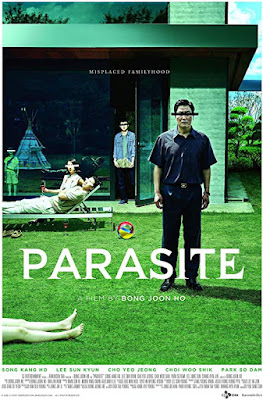

Parasite (2019)

South Korean director and screenwriter Bong Joon Ho has had a pretty good year, not only winning the big prize at Cannes last spring for this movie but also handfuls of film festival, Golden Globe, and Oscars accolades, including prizes for Best Director and Best Picture. I've been aware of Joon Ho since approximately 2006's The Host, which sets the tone for much of his work, half of an excellent monster movie jammed up with half of a repellent dysfunctional family story, a lot of it taking place in dark wet enclosed spaces. I thought The Host was overrated but the monster scenes (just barely) made it worth the stop. In fact, I don't think it was until 2013's Snowpiercer, his best before Parasite, that I started to take more of an active interest in him. Joon Ho's Mother, for example, from 2009, was overshadowed the next year by another movie by another South Korean director, Chang-dong Lee's Poetry, both having many similar maternal themes. Poetry is better than Mother. Even Joon Ho's last, Okja, I thought came with too many flaws of social critique a little too obvious and casting a little too glamorous (Jake Gyllenhaal and Tilda Swinton both deserve extended timeouts to think about their sins in it). This might be the place to make a dumb joke about Joon Ho's name, because in many ways his ideas seem to be products of hotbox sessions. Parasite, paradoxically, hits a sweet spot where his major themes—that is, disaster movies infected by family dramas—come together in a way almost impossibly gratifying. I take Parasite first as a broad critique of capitalism (complete with climate change disaster) but its biologically oriented title suggests even more profound places where Joon Ho is able to carry his narrative. The Kim family are urban working class and suffering all the pains of it—unemployed, impoverished, barely surviving on their obviously impressive wits. The patriarch (Kang-ho Song, a long-time Joon Ho player) is a driver and past owner of failed businesses. Mother (Hye-jin Jang) is a slattern. Son (Woo-sik Choi) is a dropout. Daughter and older sister (So-dam Park) turns out to be the brains of the bunch. After the son lands a job with a wealthy family, the rest of the poor family starts to move in on them, in various roles. The daughter sells herself as an art therapist for the rich family's ostensibly troubled boy (who has what might be an unnatural fascination with American Indians but more likely he's just a rowdy boy). The father gets the job of driving the rich family's limo. And the mother becomes the housekeeper. Things spiral out of control from there as they will in Joon Ho's tales, but the chaos that proceeds of family dysfunction caught up in brutal economic realities is more thoughtfully sculpted than usual this time. It's still chaos but with evident purpose beyond zany antics. The rich family is all fucked up too, of course—that family's matriarch is notably "simple," as the con artist family characterizes her, with Yeo-jeong Jo's performance really practically stealing the whole show. The point where the mansion turns out to have a hidden dungeon is the point where Joon Ho might often lose control of his material and he comes pretty close to it here again. But he holds on and you should too. It's a wild ride.

Sunday, March 22, 2020

"The Golden Man" (1954)

This long 1954 story by Philip K. Dick makes an interesting comparison with the movie made in 2007 based on it, Next. The story has all of Dick's paranoia, with a government agency out systematically hunting radiation mutants, but a lot of time is spent on setups and revelations, as we watch one of the operations at work. In the story, the mutant Cris Johnson is barely even socialized—he's never even spoken. Mutants are categorized into 87 types but he's not one of them. A lot of time is spent defining his power, which is being able to see into the future. In the movie, mutants are a non-issue. Cris (played by Nicolas Cage) is a stage magician in Las Vegas, and he can see two minutes into the future—with some exceptions. It's quite a bit different from the story, which more works through how a consciousness or brain would function with that kind of information coming in. In fact, the movie could have stood a bit more of that. It was directed by Lee Tamahori, who also directed Once Were Warriors, a movie I liked a lot. Next has star power and some indie cred, with Cage, Julianne Moore, and Jessica Biel. Cage is good in the part, more in his restrained smoldering mode. I read the story and saw the movie on the same day, both for the first time, and for once I enjoyed the movie more. It seemed more lucid about the power. In the story Cris is treated literally as if he were a god, which seemed silly. With the ordnance going off and Cage striding around unfazed, occasionally twisting aside to let a bullet pass him, the movie can be thrilling and hilarious all at once. Cris has a line in voiceover where he denies he is a god (as if speaking to the Dick story) but in his best moments in the movie that's exactly what he looks like. There's no paranoia in the movie about mutants, which was a good idea to dispense with as the X-Men and the age of Marvel loomed ever larger in 2007. There's a government agency but it's counterterrorist. The specific case at hand involves a loose nuke in the Los Angeles area, a scheme apparently run by Russians. It goes to some ridiculous and unlikely places but it always keeps its cool and the fascination with the power is infectious. Dick's story feels a bit pounded out and padded for the sake of word count, though it does retain his unique sense of paradox. The movie doesn't feel very Phildickian to me but has other ways of getting trippy that are often interesting. It feels like everybody involved was having more fun than Dick writing the story.

The Philip K. Dick Reader

The Philip K. Dick Reader

Saturday, March 21, 2020

Going to a Go-Go (1965)

From the goofy dated title, or simply contemplating the breezy mid-'60s sailboat style of the cover photo and design, it might be easy to assume this is a typical album for its times, with the old one-hit-plus-11-covers strategy of long-players (LPs) for record clubs—a blast of nostalgia at best (put this cover on the wall!) and hope the hit at least is good. If those are your expectations you're in for a treat. There are 12 songs, but first—well, first, it's Motown, and then second, it's Smokey Robinson, with a hand in writing 11 of the songs. There are no fewer than four hits on this one (a third of the album ... compare Cyndi Lauper's She's So Unusual). All four were top 20 (though none top 10), and at least a couple of them have gone on to become standards, covered by others into their own hits. Perhaps most notably that's "Tracks of My Tears," which Johnny Rivers and Linda Ronstadt had later hits with. "Ooo Baby Baby" is like that too, another hit for Linda Ronstadt and also taking its place in one of Todd Rundgren's best moments, the soul medley from A Wizard, a True Star. You might be surprised, as I was, to learn the biggest hit the album produced was the title song, which reached #11. I don't remember hearing it on the radio but the song, with a churning under-beat that drives it like a tank on rough terrain, was actually one of my favorites when I caught up with the album in the early '80s, in thrall to Jim Miller's Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll (my introduction to The Velvet Underground and Nico, Pet Sounds, and a bunch of others I badly needed catching up on). "Going to a Go-Go" made going to a go-go sound even cooler than Chic was making going to a disco sound.

For hits, that only leaves "My Girl Has Gone," which I barely know by title but remember when I hear it as part of the rich stew of Motown offerings on the radio then. That one I did hear on the radio. "Choosey Beggar" is a classic example of Smokey Robinson head play, riffing on the old "beggars can't be choosers" chestnut. It misspells the word in the title and, even more strikingly, Robinson mispronounces it in the vocal (as, approximately, "choizy"). It somehow works like a minor irritant that flushes out a lot of seductive pleasure when you sing with it. That's one of those things Smokey Robinson does so well. He's stiff and corny like a dad joke but there's a release there too. Sometimes his puns are so strained they are the irritants themselves ("I Second That Emotion," for example, which turns a plaintive declaration into Robert's Rules of Order). But the main point is that's exactly where Robinson can draw the pleasure from somehow, putting his stamp on it. And I'm just talking about his songwriting at the moment—the gorgeous vocal style is another matter entirely. Another nice one here is "From Head to Toe," which Elvis Costello & the Attractions covered in 1982 as part of Costello's apology campaign after the dustup with Delaney & Bonnie in Columbus, Ohio. I'm not missing that all these artists covering Smokey Robinson's songs are white, and in fact while I don't have that much use for the Ronstadt versions, I actually prefer the ones by Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren to the originals here. But these are great songs—all of them—and anyone who can carry a melody is going to make a credible job of putting them over. And Smokey Robinson can do much more than merely carry a melody. Is this the greatest album by Smokey Robinson & the Miracles? Is it the greatest Motown album? I wouldn't go that far. But I bet it's a whole lot better than you would think. That's the thing about Smokey Robinson, and Motown. Even the workaday stuff tends to be noticeably a cut above.

For hits, that only leaves "My Girl Has Gone," which I barely know by title but remember when I hear it as part of the rich stew of Motown offerings on the radio then. That one I did hear on the radio. "Choosey Beggar" is a classic example of Smokey Robinson head play, riffing on the old "beggars can't be choosers" chestnut. It misspells the word in the title and, even more strikingly, Robinson mispronounces it in the vocal (as, approximately, "choizy"). It somehow works like a minor irritant that flushes out a lot of seductive pleasure when you sing with it. That's one of those things Smokey Robinson does so well. He's stiff and corny like a dad joke but there's a release there too. Sometimes his puns are so strained they are the irritants themselves ("I Second That Emotion," for example, which turns a plaintive declaration into Robert's Rules of Order). But the main point is that's exactly where Robinson can draw the pleasure from somehow, putting his stamp on it. And I'm just talking about his songwriting at the moment—the gorgeous vocal style is another matter entirely. Another nice one here is "From Head to Toe," which Elvis Costello & the Attractions covered in 1982 as part of Costello's apology campaign after the dustup with Delaney & Bonnie in Columbus, Ohio. I'm not missing that all these artists covering Smokey Robinson's songs are white, and in fact while I don't have that much use for the Ronstadt versions, I actually prefer the ones by Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren to the originals here. But these are great songs—all of them—and anyone who can carry a melody is going to make a credible job of putting them over. And Smokey Robinson can do much more than merely carry a melody. Is this the greatest album by Smokey Robinson & the Miracles? Is it the greatest Motown album? I wouldn't go that far. But I bet it's a whole lot better than you would think. That's the thing about Smokey Robinson, and Motown. Even the workaday stuff tends to be noticeably a cut above.

Thursday, March 19, 2020

"The Shadowy Street" (1932)

Belgian writer Jean Ray's story has some really nice points, with an inclination he might have for making people vanish physically and permanently. It's only the second story I've read by him and it happens in both. Which isn't to say it doesn't work. I like how it's structured as a portmanteau, and even more I like the alleged source—manuscripts found in the junk from a shipping bale that burst open as it was being hauled off a dock. There's a "German manuscript" and a "French manuscript"—these old horror writers are forever turning up mysterious manuscripts, aren't they? Both detail events in the same town in Germany, in fact even the same section of town. The narrator believes one manuscript may shed light on the other, and so they do, though principally I suspect by being shoved together this way. In the German manuscript a group of women battle an invisible monster of some kind in their home. It's not exactly a ghost, and actually quite a bit like the so-called Horla from the 19th-century story by Guy de Maupassant. The women begin to pop out of existence one by one as the manuscript cuts off. In the French manuscript, a man has found a street no one else can see. Everyone else only sees a continuation of a wall. Down that street, into which the French narrator ventures finally, are houses, and in those houses are items of fantastic value, along with a stairway blocked midway up by a wall. He can take those items, pawn them with an eager fence he finds, and the next time he returns to the street they have been replaced and may be stolen and sold again. Another feature of the street is that it bends and twists sharply, and around each bend is only the same scene again. Nothing in life is ever free or easy, and making money stealing silver that replaces itself was never going to be enough for this guy, who is soon hurtling to a brutal apocalypse. "The Shadowy Street" is world-building fantasy pretty much straight up, but elliptical, churning with suggestion. I like it because I like the bent of Ray's visions. Invisible monsters appeared regularly (so to speak) in horror stories after the Maupassant, maybe not as much as vampires but more in the range of Pan. No version yet has convinced me it's a very scary monster, more like a slight panic irritant, like some ghosts, and so it is here. But I like so many other things about this story: the found manuscripts, the paired narratives, the street that no one else can see, down which is only mindless repetition and redundancy. The story feels like it's working by instinct and it works almost perfectly. It's tempting to lump Ray with a couple of his countrymen (and proximate contemporaries), the prolific mystery novelist Georges Simenon, who could write with the sharp edges of this in his "hard novels," and the Surrealist painter Rene Magritte. The shadowy street in this story, in fact, is reminiscent in its details—quotidian as well as bizarre—of many of Magritte's street scenes, like the one above (The Dominion of Light). Nice one!

The Weird, ed. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer

The Weird, ed. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer

Friday, March 13, 2020

Fantasia (1940)

USA, 125 minutes

Directors: James Algar, Samuel Armstrong, Ford Beebe Jr., Norman Ferguson, David Hand, Jim Handley, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen

Writers: Joe Grant, Dick Huerner, Lee Blair, Elmer Plummer, Phil Dike, Sylvia Moberly-Holland, Norman Wright, Albert Heath, Bianca Majolie, Graham Heid, Perce Pearce, Carl Fallberg, William Martin, Leo Thiele, Robert Sterner, John McLeish, Otto Englander, Webb Smith, Erdman Penner, Joseph Sabo, Bill Peet, Vernon Stallings, Campbell Grant, Arthur Heineman

Photography: James Wong Howe

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Paul Dukas, Igor Stravinsky, Ludwig van Beethoven, Amilcare Ponchielli, Modest Mussorgsky, Franz Schubert

Animators / editors: numerous

Cast: Deems Taylor, Leopold Stokowski

Is anyone still alive who saw this when it was new? It seems unlikely, as the release of "this new form of entertainment, Fantasia," is 80 years past now, a full lifetime. The pompous words are from the dweeby Deems Taylor, standing uncomfortably in formalwear he doesn't belong in, who is our host, master of ceremonies, and all-around Robert Osborne guy for the movie. He's really not wrong about "new form of entertainment," as the vast collaboration of Fantasia arguably produced the template, if not indeed the ultimate refinement and pinnacle, of what we'd later call music videos. Taylor, continuing, "Now, there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there's the kind that tells a definite story. Then there's the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there's a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake."

As it happens, the third kind tends to be my favorite here and it seems to be what gets Taylor most amped up himself, as when, after the intermission (Fantasia is also old-fashioned in many small comforting ways), he carries on a conversation with "the soundtrack," represented by psychedelic symmetrical shapes and colors corresponding to musical instruments playing. In many ways it's the forerunner to computer screensavers and those hypnotic visualizers digital music players used to have.

Directors: James Algar, Samuel Armstrong, Ford Beebe Jr., Norman Ferguson, David Hand, Jim Handley, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen

Writers: Joe Grant, Dick Huerner, Lee Blair, Elmer Plummer, Phil Dike, Sylvia Moberly-Holland, Norman Wright, Albert Heath, Bianca Majolie, Graham Heid, Perce Pearce, Carl Fallberg, William Martin, Leo Thiele, Robert Sterner, John McLeish, Otto Englander, Webb Smith, Erdman Penner, Joseph Sabo, Bill Peet, Vernon Stallings, Campbell Grant, Arthur Heineman

Photography: James Wong Howe

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Paul Dukas, Igor Stravinsky, Ludwig van Beethoven, Amilcare Ponchielli, Modest Mussorgsky, Franz Schubert

Animators / editors: numerous

Cast: Deems Taylor, Leopold Stokowski

Is anyone still alive who saw this when it was new? It seems unlikely, as the release of "this new form of entertainment, Fantasia," is 80 years past now, a full lifetime. The pompous words are from the dweeby Deems Taylor, standing uncomfortably in formalwear he doesn't belong in, who is our host, master of ceremonies, and all-around Robert Osborne guy for the movie. He's really not wrong about "new form of entertainment," as the vast collaboration of Fantasia arguably produced the template, if not indeed the ultimate refinement and pinnacle, of what we'd later call music videos. Taylor, continuing, "Now, there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there's the kind that tells a definite story. Then there's the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there's a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake."

As it happens, the third kind tends to be my favorite here and it seems to be what gets Taylor most amped up himself, as when, after the intermission (Fantasia is also old-fashioned in many small comforting ways), he carries on a conversation with "the soundtrack," represented by psychedelic symmetrical shapes and colors corresponding to musical instruments playing. In many ways it's the forerunner to computer screensavers and those hypnotic visualizers digital music players used to have.

Monday, March 09, 2020

Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (2019)

I was pretty excited when I first heard that director and screenwriter Quentin Tarantino's next movie was going to be about the Charles Manson murders, and even more when I heard it was aligning itself as a "once upon a time" movie, which I believe started with Sergio Leone's "in the West" and "in America" and has since continued with settings in China, Mexico, Anatolia, London, Venice, and elsewhere (... leave it to Tarantino to go too far by throwing in an unnecessary ellipsis). But something shifted for me with the casting announcements and other promotion, and by the time the movie came out last summer I was all the way on the other side of the fence, expecting the worst and avoiding it. And, self-fulfilling prophecy or otherwise, that's what I found when I finally got here. What crystallized was that everything since Death Proof has been weak and getting weaker, as Tarantino has spent the last decade systematically and self-consciously trying to make his sadism and the whole elaborate Grand Guignol aesthetic / shtick more palatable by putting them in the service of things universally recognized as right and good. So he has been punching at Nazis, slavery, and mean people in the West, worthy targets all. The object of irritation supposedly producing one more Tarantino pearl this time is hippies from the '60s, which is all fun and games until the moment arrives when the hippie chick with the dirty bare feet is having her head bashed into every solid surface and object available, and the blood is flying. As Lou Reed put it (in a far more sensitive context), you just know that bitch will never fuck again. That scene alone, in the ludicrous finish, goes on for quite some time.

I thought the conceit of these once-upon movies is that the fairy tale title is juxtaposed ironically against the grim settings and actions, but Tarantino's entry is not only set in glamorous Hollywood but also has a fairy tale ending. The only thing missing is a quick bio title card so we can find out how Sharon Tate's life and career went after August 1969 (what did she name the baby? did she finally divorce Roman Polanski and marry Jay Sebring? inquiring minds want to know). Everything about this movie is flabby. Not one of the maximally male wall of stars is particularly good (Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Timothy Olyphant, Al Pacino, Bruce Dern, et fucking cetera, and don't forget Kurt Russell, who inexplicably turns into the voiceover narrator in the second half), nor is the phalanx of gorgeous but obviously second-tier as intended females much better (Margot Robbie, Margaret Qualley, Dakota Fanning, Lena Dunham [!], Dreama Walker). Wasted, all. The soundtrack registers only occasionally, and even Tarantino's trademark zingy dialogue is closer to flatulent. Wait, I take that back about the players. Mike Moh as Bruce Lee was very entertaining. And there's no denying Tarantino's skills as a filmmaker—a few scenes work pretty well. I went into this one with the lowest possible expectations, hoping that paradoxically it would surprise me. That's how it worked with Death Proof, which I avoided at first because of the reviews and then found one of his best when I finally got to it. But Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood is not one of Tarantino's best. It is merely better than The Hateful 8, which can be said about thousands of movies.

I thought the conceit of these once-upon movies is that the fairy tale title is juxtaposed ironically against the grim settings and actions, but Tarantino's entry is not only set in glamorous Hollywood but also has a fairy tale ending. The only thing missing is a quick bio title card so we can find out how Sharon Tate's life and career went after August 1969 (what did she name the baby? did she finally divorce Roman Polanski and marry Jay Sebring? inquiring minds want to know). Everything about this movie is flabby. Not one of the maximally male wall of stars is particularly good (Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Timothy Olyphant, Al Pacino, Bruce Dern, et fucking cetera, and don't forget Kurt Russell, who inexplicably turns into the voiceover narrator in the second half), nor is the phalanx of gorgeous but obviously second-tier as intended females much better (Margot Robbie, Margaret Qualley, Dakota Fanning, Lena Dunham [!], Dreama Walker). Wasted, all. The soundtrack registers only occasionally, and even Tarantino's trademark zingy dialogue is closer to flatulent. Wait, I take that back about the players. Mike Moh as Bruce Lee was very entertaining. And there's no denying Tarantino's skills as a filmmaker—a few scenes work pretty well. I went into this one with the lowest possible expectations, hoping that paradoxically it would surprise me. That's how it worked with Death Proof, which I avoided at first because of the reviews and then found one of his best when I finally got to it. But Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood is not one of Tarantino's best. It is merely better than The Hateful 8, which can be said about thousands of movies.

Sunday, March 08, 2020

Blue Guitar Highway (2011)

I am days late and dollars short at this point, obviously, but I'm still having a hard time judging Paul Metsa's jabbering eloquent memoir for what it is. It's possible that you had to be there, though "there" covers a lot of territory. Metsa comes from the Northern Minnesota Iron Range country, specifically the town of Virginia, less than 30 miles east of Hibbing, where Bob Dylan grew up (and about 60 miles north of Cloquet, where I was born and lived until I was nearly 5). Metsa is a long-time Minneapolis blues and folk player, arriving in the late '70s with his band Cats Under the Stars. Full disclosure (as if it matters), I knew him during my tenure at the alternative newsweekly City Pages (in 1984 and 1985) and he was always kind to me during those strange and trying times, having me over to his place to listen to records and always a friendly face out and about. I learned a lot from him and it was always a good time. My own tastes can run a little cool toward his music projects, but he is also one of those restless improvising souls and that means he has nights where he is extraordinarily good, usually on his own with a guitar, electric or otherwise, or sometimes playing the piano. This book tells his story. As a working musician he counts his high points meeting and playing with some of his heroes, such as Bruce Springsteen. His single greatest achievement, of course, is simply surviving as a musician. When this book was published nine years ago, 5,000 was the number he was using for his total gigs played. He's put out several albums over the years and a few singles too. I like this book because I like him so much, and also I love reading about all the Twin Cities landmarks, which bring me back. I haven't lived there since 1985. I especially appreciated learning the inside story of how hard he worked—for five years!—on what was ultimately the losing side of saving the original Guthrie Theater, destroyed in 2006. Metsa rightly refers to it as Minnesota's Carnegie Hall, and the list of shows he saw and played there (including his own sold-out turn in the '90s) is impressive and turns you green with envy. I saw some good ones there myself. I was shocked to learn of its demise and still am. Metsa knew practically everyone in town—he has great stories about Bob Stinson and Bob Mould, and doesn't even deny his friendship with Norm Coleman (though it seems like his acquaintance with Paul Wellstone is what he treasures more). Perhaps best of all, though it should not have surprised me, Metsa is a great writer too, his sheer energy powering torrents of language in terrific bursts. I was as happy to learn of all his further adventures as I once was to let him put on the next record. Long may he run.

In case the library is closed due to pandemic.

In case the library is closed due to pandemic.

Friday, March 06, 2020

The Young and the Damned (1950)

Los olvidados, Mexico, 80 minutes

Director: Luis Buñuel

Writers: Luis Alcoriza, Luis Buñuel

Photography: Gabriel Figueroa

Music: Rodolfo, Halffter, Gustavo Pittaluga

Editor: Carlos Savage

Cast: Roberto Cobo, Alfonso Mejia, Miguel Inclan, Estela Inda, Alma Delia Fuentes, Mario Ramirez

Spanish Surrealist director and cowriter Luis Buñuel was naturalized as a Mexican citizen in 1949, which may account in part for the foray into social realism he takes with The Young and the Damned. Various business considerations no doubt came into play as well. It was probably never easy making a living as a midcentury Spanish Surrealist filmmaker. The movie is better known in cineaste circles by its original name, Los olvidados, which translates literally as "the forgotten ones." I think it bears comparison, as Latino social realism, much more with movies such as City of God or maybe Amores Perros or even Roma than with other pictures in Buñuel's catalog before or after. That would include most famously, perhaps, 1929's Un Chien Andalou and 1972's The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but don't forget Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel from the early '60s. I would class The Young and the Damned more as an outlier, in short, even if it is presently considered Buñuel's second-greatest picture in the critical roundup over at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

You'd be forgiven for wondering what happened to the Surrealism, but it is actually here, caught briefly in a dream sequence and more generally in the very harsh tenor of this picture (Surrealism, after all, has always been about brainstem perceptions as much as anything). The harshness also suits the social realism, of course. I have no problems with that in theory. I've been fascinated all my life, since at least S.E. Hinton's remarkable novel The Outsiders, with stories of juvenile delinquency, violence, and disaffection. But Buñuel's treatment is so primitive it's almost too much, even in the relatively compressed running time. It's a low-budget affair, obviously, but practically seems to wallow in its conditions, a kind of pornography of despair on some levels. Set in Mexico City, these down-and-outers have zero glamour, no doubt as intended. A surprising amount of time in this picture is devoted to people heaving rocks at one another, and inflicting terrible damage too, including death. They have other ways to fight, and the movie has other themes too, but the rock-throwing may best epitomize the plight Buñuel is depicting here. When you have nothing, and the ground you walk on is stony already, well, what do you think you're supposed to do?

Director: Luis Buñuel

Writers: Luis Alcoriza, Luis Buñuel

Photography: Gabriel Figueroa

Music: Rodolfo, Halffter, Gustavo Pittaluga

Editor: Carlos Savage

Cast: Roberto Cobo, Alfonso Mejia, Miguel Inclan, Estela Inda, Alma Delia Fuentes, Mario Ramirez

Spanish Surrealist director and cowriter Luis Buñuel was naturalized as a Mexican citizen in 1949, which may account in part for the foray into social realism he takes with The Young and the Damned. Various business considerations no doubt came into play as well. It was probably never easy making a living as a midcentury Spanish Surrealist filmmaker. The movie is better known in cineaste circles by its original name, Los olvidados, which translates literally as "the forgotten ones." I think it bears comparison, as Latino social realism, much more with movies such as City of God or maybe Amores Perros or even Roma than with other pictures in Buñuel's catalog before or after. That would include most famously, perhaps, 1929's Un Chien Andalou and 1972's The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but don't forget Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel from the early '60s. I would class The Young and the Damned more as an outlier, in short, even if it is presently considered Buñuel's second-greatest picture in the critical roundup over at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

You'd be forgiven for wondering what happened to the Surrealism, but it is actually here, caught briefly in a dream sequence and more generally in the very harsh tenor of this picture (Surrealism, after all, has always been about brainstem perceptions as much as anything). The harshness also suits the social realism, of course. I have no problems with that in theory. I've been fascinated all my life, since at least S.E. Hinton's remarkable novel The Outsiders, with stories of juvenile delinquency, violence, and disaffection. But Buñuel's treatment is so primitive it's almost too much, even in the relatively compressed running time. It's a low-budget affair, obviously, but practically seems to wallow in its conditions, a kind of pornography of despair on some levels. Set in Mexico City, these down-and-outers have zero glamour, no doubt as intended. A surprising amount of time in this picture is devoted to people heaving rocks at one another, and inflicting terrible damage too, including death. They have other ways to fight, and the movie has other themes too, but the rock-throwing may best epitomize the plight Buñuel is depicting here. When you have nothing, and the ground you walk on is stony already, well, what do you think you're supposed to do?

Thursday, March 05, 2020

"The White People" (1904)

The Welsh mystic Arthur Machen has a fair amount of stature in horror and fantasy circles, perhaps best known for his long story, "The Great God Pan," published in 1894, which set off a goat-god theme around the turn of the century that many contemporaries worked with in the same way they did vampires and werewolves (that is, probably for commercial reasons). Stephen King apparently has "Pan" on his short list of the very best. I admit I struggled with it, but this story is something else. Because we need to make the point in a realm dominated by H.P. Lovecraft, the story has nothing to do with race. These white people are more like silver and glowing when they are seen at all, which is rarely, and they are mysterious to the bottom (note the Penguin cover interpretation above). There's a critique to make about sexism, misogyny, and fear of women here, yes, but in many ways I think this strangely stirring story might get past that in certain ways. It comes in two parts—a frame, at beginning and briefly at end, featuring a colloquy between two intellectual men on the nature of sin, and a long middle section, a diary of an adolescent girl, a document one of the men passes to the other to read. The frame is necessary as it articulates the themes and sets expectations for the main narrative, notably the idea that sin is not transgression of moral laws but of physical ones. People who flout laws and norms must be dealt with, of course, but the argument is they are not truly sinners. The second man is intrigued and would like to subscribe to the first man's newsletter. He gets the diary to read.

This is a basic of "weird" fiction, a subset of fantasy and/or horror, distinct by its treatment of the unknown. We may have a fear of the unknown but weird fiction, if I'm understanding, wants to focus more on the unknown than the fear. If you're scared you're on your own, because that's how it is in the irrational world. Weird fiction merely continues to catalog the details. And so to the girl's diary. The critic S.T. Joshi has my favorite observation on "The White People," calling it "a masterpiece of indirection, a Lovecraft plot told by James Joyce." The diary is the longest part of the story but it doesn't have many paragraphs. It's not run-on but lucid and artful, with numerous digressions and embedded stories. It's easy to get lost but not hard to find oneself again, much like the action in the story, a kind of Alice in Wonderland journey through a copse. It's studded with made-up words and terms (Lord Dunsany for one had to be a fan), used so naturally they effectively suggest enormous worlds just beyond. I will say I'm glad I read this with an inline dictionary because that helped separate the made-up from the historical. Historical verity might be in the minority here, but it is here. This girl's adventures with magic and the irrational are practically hypnotic by the rhythms of the language and narrative, with stories within stories within stories, churning well known strokes out of the Bible thrown up like debris, across an unknowable landscape that becomes second nature. In the end her story has nowhere to go and in the end it gets there, abruptly cut off when the diary ends. But the world it details does linger on. My favorite character is the girl's nurse, who the girl remembers but who has disappeared at the time she writes her diary. Nurse taught the girl a good deal when she was younger, even as an infant. The suggestion of these White People, living in their White Lands, is deceptively simple, and penetrating. It somehow turns everything upside down.

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Read story online.

This is a basic of "weird" fiction, a subset of fantasy and/or horror, distinct by its treatment of the unknown. We may have a fear of the unknown but weird fiction, if I'm understanding, wants to focus more on the unknown than the fear. If you're scared you're on your own, because that's how it is in the irrational world. Weird fiction merely continues to catalog the details. And so to the girl's diary. The critic S.T. Joshi has my favorite observation on "The White People," calling it "a masterpiece of indirection, a Lovecraft plot told by James Joyce." The diary is the longest part of the story but it doesn't have many paragraphs. It's not run-on but lucid and artful, with numerous digressions and embedded stories. It's easy to get lost but not hard to find oneself again, much like the action in the story, a kind of Alice in Wonderland journey through a copse. It's studded with made-up words and terms (Lord Dunsany for one had to be a fan), used so naturally they effectively suggest enormous worlds just beyond. I will say I'm glad I read this with an inline dictionary because that helped separate the made-up from the historical. Historical verity might be in the minority here, but it is here. This girl's adventures with magic and the irrational are practically hypnotic by the rhythms of the language and narrative, with stories within stories within stories, churning well known strokes out of the Bible thrown up like debris, across an unknowable landscape that becomes second nature. In the end her story has nowhere to go and in the end it gets there, abruptly cut off when the diary ends. But the world it details does linger on. My favorite character is the girl's nurse, who the girl remembers but who has disappeared at the time she writes her diary. Nurse taught the girl a good deal when she was younger, even as an infant. The suggestion of these White People, living in their White Lands, is deceptively simple, and penetrating. It somehow turns everything upside down.

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Read story online.

Sunday, March 01, 2020

The Moviegoer (1961)

I was pretty sure a well-liked award-winning novel with this title would be one I'd go for, even though it somehow evaded me most of my life and a misbegotten attempt at another Walker Percy novel (Lancelot, I think) had not gone well. But I did not like The Moviegoer very much. It has some resemblance to The Great Gatsby and Appointment in Samarra, with a quixotic single white man of 30, a born daydreamer now more urgently required to grow up. The moviegoing aspect was more metaphorical and symbolic than merely moviegoing. It still got some things right on that score but they seem old now, coming from a time when Paul Newman was just on the horizon. My main complaint was the aimlessness of the narrative, which mimics the aimlessness of its main character, one Binx Bolling, an insufferable Southern gentleman twit. He lives in a suburb of New Orleans and works as a stockbroker in a local office. He gets along all right, kaff-kaff. He's a womanizer, targeting a series of secretaries. His family is fractured and complicated. He appears to be close to an aunt, and a cousin is a romantic interest. He has his problems. He's not likable. But he is a very good writer—Percy, I mean, by way of Binx, who is the official first-person narrator. Every sentence here glitters. I read a print version and missed the online dictionary access of kindle products because my vocabulary was challenged and I was too lazy to go look things up. I wish he would have talked more about movies. His obsession felt convincing and familiar but often alien too. He had a thing about theater architecture, for example. I might have shared it even as recently as the '70s, but the years and decades of multiplexes and video rental outlets have drummed it out of me. He also sorts his movies more by performers than directors—well, I suppose most people do. But movies are really beside the point in this novel, where "moviegoer" is more like someone passively gazing at life—actively pursuing passively gazing, or something like that. It's just an image. Much like his sex life, which is a little reminiscent of the smug Nails song "88 Lines About 44 Women." It all appears to relate back on deeper levels (I'm on the Wikipedia article now to shore up my case for why this exists) to existential considerations, Soren Kierkegaard, Dante, and naturally the status and future of Southern writing. The Moviegoer is resolutely inert, with formal likenesses to The Stranger by Albert Camus. I came away from it with some vague hostility, the result as much as anything of disappointed expectations set by the title, and also frustrated by all the beautiful sentences in the service of allusive complications too tedious to follow. At the same time I suspect, somewhat uneasily, that The Moviegoer could become one I like more with another reading. At the moment I can't bear to think of that. But so many people do like it so much.

In case the library is closed due to pandemic.

In case the library is closed due to pandemic.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)