Having slept on it, I've decided to take Alice Munro's story as a dream sequence. There's even enough information to support specific points of context, though I understand I'm making leaps here. The dreamer is Jinny, the main character (and probably the narrator), but the dream is from a later time, after surviving the cancer that is described here. She survived it but her life, however grateful she may be, is inevitably fractured. In the dream (in my version), she is in a scene following a visit to the doctor where he told her her condition has begun to go into remission. Her husband Neal is making it impossible to talk to him. He is a strange and unsettling presence in this story—her husband, but as disconnected from her as it is possible to be. He drives her back from the doctor's appointment but won't interact with her directly, only talks at her and uses others as distraction. Especially in light of their age difference—she is 42 and he is 58—he behaves bizarrely. He has hired an entirely inappropriate home care assistant, Helen, a teen who is in the legal system. Everything he does in this story is more to accommodate Helen than Jinny. There's even a sense Neal is flirting with Helen. The detours they take on the way home from the doctor are weird and time-consuming. All the places this remarkable story goes are charged with shocking behavior, decisions, words said aloud. This floating bridge—how is it anything but a dream product? What's most vivid about the story is Jinny's will to live. She is right at death in every way, still in chemotherapy, still in the shock of the diagnosis. She knows it is close and seems to be considering resigning herself to it, but she resists too. The appearance of the adolescent Ricky brings a sexual charge, which jolts Jinny from merely wanting to resist death to finding the strength and reason to do it. Or that's how I read it. There's a crackling discomfort to this story that gnaws away at the reader, especially as we start to piece together the action and Jinny herself. People persist in not behaving naturally but only slightly out of key. Something always feels wrong though that might be a matter of witnessing the shabby way Jinny is treated, or dreams she was treated. It also seems a little too shabby. The story ends on a high note: "What she felt was a lighthearted compassion, almost like laughter. A swish of tender hilarity, getting the better of all her sores and hollows, for the time given." In my version that's her waking up.

In case it's not at the library.

Sunday, December 29, 2019

Friday, December 27, 2019

The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

USA, 129 minutes

Director: John Ford

Writers: Nunnally Johnson, John Steinbeck

Photography: Gregg Toland

Music: Alfred Newman

Editor: Robert L. Simpson

Cast: Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine, Charley Grapewin, Zeffie Tilbury, Dorris Bowdon, Eddie Quillan, Russell Simpson, O.Z. Whitehead, John Qualen, Ward Bond

The Grapes of Wrath was remarkably successful as both a novel and then a movie, one of those instant outsize media successes we like to produce in this country when we can. John Steinbeck's novel was published in 1939 and quickly became emblematic of the Dust Bowl environmental disaster of the Great Depression, accompanied by the arrival of big agribusiness capitalism and a massive migration West. It's a kind of small-bore version of Uncle Tom's Cabin, intersecting history right in the moment. It was banned and burned and yapped about on rightwing talk radio, but it also won a National Book Award and a Pulitzer, and it was the work most often mentioned when Steinbeck won his Nobel in 1962. Almost immediately upon publication Darryl F. Zanuck paid a princely sum for the movie rights and then this John Ford version came out the following year, ultimately winning Oscars for director Ford and for Jane Darwell as Ma Joad, with five more nominations to spark the evening, including Best Picture. It all happened in just a couple of years, during the high hysterical times as the Depression moderated and a world war loomed, 1939 to 1942, Hollywood's most characteristic years.

The book and movie now appear regularly on long-faced lists of important great things, and the truth is they both are great, or capable of it, though arguably dogged by some slight odor of sanctimony. I was surprised to find a contemporary Time review, by Whittaker Chambers of all people (via Wikipedia), which declared the movie "possibly the best picture ever made from a so-so book"—surprised because if anything I see it the other way. The movie version of The Grapes of Wrath, as impressive as it is, is finally merely another case of a movie not being as good as the book. If it's only going to be one, read the book. This is for specific reasons, notably the treatment of the ending. Yet even falling short of this extraordinary novel can still mean the movie is pretty good and deserves its accolades too.

Director: John Ford

Writers: Nunnally Johnson, John Steinbeck

Photography: Gregg Toland

Music: Alfred Newman

Editor: Robert L. Simpson

Cast: Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine, Charley Grapewin, Zeffie Tilbury, Dorris Bowdon, Eddie Quillan, Russell Simpson, O.Z. Whitehead, John Qualen, Ward Bond

The Grapes of Wrath was remarkably successful as both a novel and then a movie, one of those instant outsize media successes we like to produce in this country when we can. John Steinbeck's novel was published in 1939 and quickly became emblematic of the Dust Bowl environmental disaster of the Great Depression, accompanied by the arrival of big agribusiness capitalism and a massive migration West. It's a kind of small-bore version of Uncle Tom's Cabin, intersecting history right in the moment. It was banned and burned and yapped about on rightwing talk radio, but it also won a National Book Award and a Pulitzer, and it was the work most often mentioned when Steinbeck won his Nobel in 1962. Almost immediately upon publication Darryl F. Zanuck paid a princely sum for the movie rights and then this John Ford version came out the following year, ultimately winning Oscars for director Ford and for Jane Darwell as Ma Joad, with five more nominations to spark the evening, including Best Picture. It all happened in just a couple of years, during the high hysterical times as the Depression moderated and a world war loomed, 1939 to 1942, Hollywood's most characteristic years.

The book and movie now appear regularly on long-faced lists of important great things, and the truth is they both are great, or capable of it, though arguably dogged by some slight odor of sanctimony. I was surprised to find a contemporary Time review, by Whittaker Chambers of all people (via Wikipedia), which declared the movie "possibly the best picture ever made from a so-so book"—surprised because if anything I see it the other way. The movie version of The Grapes of Wrath, as impressive as it is, is finally merely another case of a movie not being as good as the book. If it's only going to be one, read the book. This is for specific reasons, notably the treatment of the ending. Yet even falling short of this extraordinary novel can still mean the movie is pretty good and deserves its accolades too.

Sunday, December 22, 2019

Dreaming the Beatles (2017)

Rob Sheffield takes possession of the Beatles in a deceptively effortless way. He's a little defensive on some of his points, forcefully turning his 1966 birthdate into an advantage rather than disadvantage (a little like me arguing for possession of Louis Jordan, but OK). His starting point, much like Greil Marcus's for Elvis Presley in Dead Elvis, is that the Beatles never stopped growing and being important just because the band broke up. His most persuasive argument for me was simply pointing out that the album 1, released in 2000—a collection of the Beatles' 27 #1 hits, which everybody who cared had to own by then—has been the best-selling album for most of this century so far (it's now #2 after Adele's 21, which only overtook it this year). Sheffield covers all the familiar ground here: Ed Sullivan, the movies, Bob Dylan, Rubber Soul and Revolver, Jesus, the White Album, etc. He is particularly good on Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, with one of the best analyses of that album and its place I've seen. Then, without so much as a speed bump, he carries on talking about the solo careers in the '70s and early nostalgia products such as the Red Album and Blue Album. This was the most surprising and even refreshing view for me—every time he casually zigged and zagged between '60s Beatles and '70s Beatles I had to reorient a little. I like many of the solo Beatles albums (and I like Double Fantasy a good deal more than he does) but I have always seen a bright line between the Beatles and what came after. But I'm convinced now he's right. The Beatles were unimaginably huge in their time. We've seen nothing like it since in popular culture. Yet they have become even bigger since. By the one obvious measure, for most of the 21st century, which started 30 years after they broke up and one of them dead, they owned the #1 album. Getting down to cases with this book—which is a pleasure to read—I find myself closer to Sheffield than I would have imagined, but often with strong disagreements too. He's a John Lennon / Rubber Soul partisan whereas I had made him for Paul McCartney / White Album. He actually went down the anti-Paul road with the rest of us, turning it around finally (as the new majority coalition coalesced) in the '90s (I was a little slower). I like George more than he does and he likes Ringo more than I do. He is vastly more versed on the lore, the bootlegs, and YouTube videos. There was a lot for me to learn here. I had already learned, maybe with Ian MacDonald's Revolution in the Head (on which Sheffield sounds a little dubious), that there's always more to learn with the Beatles, and infinitely more variation in taste on specific cases. Ultimately I think Dreaming the Beatles is a bit of an odd duck—I worry that like 1991's Dead Elvis it is actually heralding the beginning of the end—but it definitely belongs in the canon of Beatles literature.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Thursday, December 19, 2019

"The Crown Derby Plate" (1933)

Marjorie Bowen's story is another ghost story set in the boggy foggy countryside of England at Christmastime. Its single best feature is caught in the opening line: "Martha Pym said that she had never seen a ghost and that she would very much like to do so, 'particularly at Christmas, for you can laugh as you like, that is the correct time to see a ghost.'" Yes, laugh as you like, Christmas is the time for scary ghost stories. Andy Williams sings it in "It's the Most Wonderful Time of the Year." Charles Dickens understood it, and filmmakers from Ingmar Bergman (Fanny and Alexander) to Tim Burton (The Nightmare Before Christmas), though Bob Clark (original mastermind of Black Christmas) may not exactly be getting it. This is an admirably moody story, reminiscent of the stylish Woman in Black movies. Martha Pym, collector of fine china and proprietor of an antique store in London, is on her annual holiday visit to her cousins when she learns an abandoned mansion in the area is now occupied. The previous owner had died there decades before—at the estate sale that followed, Miss Pym had found a nearly complete set of Crown Derby china. It is now her hope that the present resident, whoever it is, may have found the missing plate. Her journey to the mansion and her encounter with the eccentric who lives there is a nicely done set piece of atmosphere. It's not hard to see where it's going but it's still a bit jarring when we get there. Bowen, who is perfectly genteel—the story is really more of a cozy—strikes the creepy note late, with intimations of "that smell," leaving us with a distinct if fleeting sense of the clammy and unpleasant in that mansion. But one reason a Christmas setting can be so effective is that things like "that smell" can just be left to lie there, as the spirit of the gaudy cheerful season presses all forward, jingle bells ringing. It's the contrast, at Christmas. Bowen doesn't even need to mention things like extremes of darkness. Even in 1933 she knows we bring all our own baggage to the story one way or another at this time of year. Merry Christmas all!

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Realms of Darkness, ed. Mary Danby (out of print)

Read story online.

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Realms of Darkness, ed. Mary Danby (out of print)

Read story online.

Sunday, December 15, 2019

Faceless Killers (1991)

[False start here.]

Full disclosure, my blog is littered with abandoned projects. One I've been gnawing at for some time is the police procedural, mainly in fiction but some on TV and at the movies too. Early on, because 10 years ago they were everywhere you looked, I flailed at Nordic noir in the form of Stieg Larsson's so-called (so-translated) Girl With the Dragon Tattoo novels (the first two, never made it to the third), and then the false start at Henning Mankell's Kurt Wallander novels. Wallander is a police detective in a small city in southern Sweden, his stories set mostly in the '90s. Then an Amazon deal opened up most of Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series to me in a convenient way. When I remembered the influence McBain had on Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, the path to Nordic noir became more clear. As a curious aside, I saw an interview with Maj Sjöwall from about 2014 (as I recall), in which she stated flatly that she found Henning Mankell boring. I worried about that, circling back to Faceless Killers again to consider going through Mankell's 11 or so Kurt Wallander tomes. But I did not find it boring at all—in fact, it was even more interesting with its themes of immigrant tensions and hostilities. It features vigilante white nationalist groups killing immigrants, especially immigrants of color, for the sake of terror. It seemed far away and imaginary when I wrote my 2012 review and so much more starkly real now. Faceless Killers might be the one to read if you only read one. So my plan now is on to the rest of them. As a meandering point of interest, other police procedural-related items I would like to get to from there include finishing the Dragon Tattoo trilogy and its TV and movie productions, continuing with the Law & Order seasons, maybe Hill Street Blues, and eventually the Jack Webb empire, including especially Adam-12. We'll see how far I get.

In case it's not at the library.

Full disclosure, my blog is littered with abandoned projects. One I've been gnawing at for some time is the police procedural, mainly in fiction but some on TV and at the movies too. Early on, because 10 years ago they were everywhere you looked, I flailed at Nordic noir in the form of Stieg Larsson's so-called (so-translated) Girl With the Dragon Tattoo novels (the first two, never made it to the third), and then the false start at Henning Mankell's Kurt Wallander novels. Wallander is a police detective in a small city in southern Sweden, his stories set mostly in the '90s. Then an Amazon deal opened up most of Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series to me in a convenient way. When I remembered the influence McBain had on Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, the path to Nordic noir became more clear. As a curious aside, I saw an interview with Maj Sjöwall from about 2014 (as I recall), in which she stated flatly that she found Henning Mankell boring. I worried about that, circling back to Faceless Killers again to consider going through Mankell's 11 or so Kurt Wallander tomes. But I did not find it boring at all—in fact, it was even more interesting with its themes of immigrant tensions and hostilities. It features vigilante white nationalist groups killing immigrants, especially immigrants of color, for the sake of terror. It seemed far away and imaginary when I wrote my 2012 review and so much more starkly real now. Faceless Killers might be the one to read if you only read one. So my plan now is on to the rest of them. As a meandering point of interest, other police procedural-related items I would like to get to from there include finishing the Dragon Tattoo trilogy and its TV and movie productions, continuing with the Law & Order seasons, maybe Hill Street Blues, and eventually the Jack Webb empire, including especially Adam-12. We'll see how far I get.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, December 13, 2019

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

USA, 100 minutes

Director: John Huston

Writers: John Huston, Dashiell Hammett

Photography: Arthur Edeson

Music: Adolph Deutsch

Editor: Thomas Richards

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet, Elisha Cook Jr., Barton MacLane, Lee Patrick, Ward Bond, Jerome Cowan

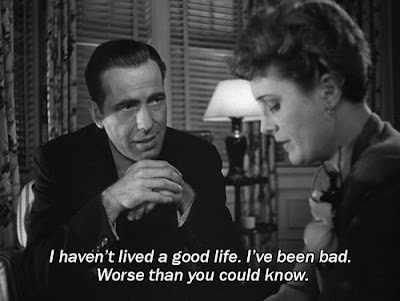

If I could find some way to rank my favorite movies based on the number of times I've seen them (which seems like a reasonable metric), The Maltese Falcon would likely make the top 10. I discovered it when I was still a teen, watched it many times on TV and in retro theaters, rediscovered it in my 20s and then in my 30s. It seems to be good for practically any occasion. The parts intended to be most powerful—for example, those speeches at the end about love and betrayal between Humphrey Bogart as detective Sam Spade and Mary Astor as a scandalous woman of many aliases—have actually worked on me once or twice (I do love the image near the end of Mary Astor in an elevator, behind bars, going down). More often now I appreciate seeing a bunch of professionals busy on some of their best work, starting with Dashiell Hammett who wrote the original novel, one of his best.

In fact, the credits seem a little confused about who matters among these professionals. Gladys George as the widow of Spade's partner is featured with Bogart, Astor, and Peter Lorre in the opening titles, though she barely makes an impression (not George's fault—it's the way the role was written for the picture). Sydney Greenstreet makes the second plateful of names, but there's no mention of Elisha Cook Jr. until the closing credits. It's a commercial film, but The Maltese Falcon is no Hollywood glamour romp of movie stars—instead, it's more like a parade of character actors, starting with Bogart, and working all the way down to the ubiquitous Ward Bond (the Kevin Bacon of his era), James Burke, John Hamilton, and Walter Huston—hey-that-guys one and all. Out of curiosity I decided to keep track of how long it took to get to the main ones.

Director: John Huston

Writers: John Huston, Dashiell Hammett

Photography: Arthur Edeson

Music: Adolph Deutsch

Editor: Thomas Richards

Cast: Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet, Elisha Cook Jr., Barton MacLane, Lee Patrick, Ward Bond, Jerome Cowan

If I could find some way to rank my favorite movies based on the number of times I've seen them (which seems like a reasonable metric), The Maltese Falcon would likely make the top 10. I discovered it when I was still a teen, watched it many times on TV and in retro theaters, rediscovered it in my 20s and then in my 30s. It seems to be good for practically any occasion. The parts intended to be most powerful—for example, those speeches at the end about love and betrayal between Humphrey Bogart as detective Sam Spade and Mary Astor as a scandalous woman of many aliases—have actually worked on me once or twice (I do love the image near the end of Mary Astor in an elevator, behind bars, going down). More often now I appreciate seeing a bunch of professionals busy on some of their best work, starting with Dashiell Hammett who wrote the original novel, one of his best.

In fact, the credits seem a little confused about who matters among these professionals. Gladys George as the widow of Spade's partner is featured with Bogart, Astor, and Peter Lorre in the opening titles, though she barely makes an impression (not George's fault—it's the way the role was written for the picture). Sydney Greenstreet makes the second plateful of names, but there's no mention of Elisha Cook Jr. until the closing credits. It's a commercial film, but The Maltese Falcon is no Hollywood glamour romp of movie stars—instead, it's more like a parade of character actors, starting with Bogart, and working all the way down to the ubiquitous Ward Bond (the Kevin Bacon of his era), James Burke, John Hamilton, and Walter Huston—hey-that-guys one and all. Out of curiosity I decided to keep track of how long it took to get to the main ones.

Thursday, December 12, 2019

"The Four-Fifteen Express" (1866)

English novelist Amelia B. Edwards's most famous ghost story is called "The Phantom Coach," a corker in the mode of Washington Irving and pretty good. But this is the one I found in the massive, uneven, yet always promising Realms of Darkness collection edited by Mary Danby. This story is not bad either, with a somber December mood, but proceeds more like a crime case with no resolution, built on the evidence and an investigation. In many ways it's closer to a cozy, or perhaps even detective fiction, than horror. A man, the one telling the story, gets on a train to visit a friend and his family in the English countryside at Christmas. He's upper-class, a diplomat or legal figure of some sort. He looks forward to his visit, to a break from his work, and to traveling alone, but just as the train starts another man joins him in his compartment. He is a slight acquaintance and mutual friend of the people he is traveling to visit. This late-arriving man is "loquacious, self-important, full of his pet project," and is soon droning along like the clacking train tracks themselves. Our man is bored and keeps drowsing off. The late-arriving man is offended because he considers himself and his story so interesting. Suddenly he has business elsewhere and gets off the train, vanishing entirely from the platform, as if in a puff. Our man, having arrived at his destination, relates the encounter to his hosts, which makes them extraordinarily uncomfortable. Three months earlier, the late-arriving talker had embezzled a large sum of money and disappeared. Our man's story thus makes no sense, but he also has concrete evidence it happened. The police are interested, and the company that was embezzled is interested. But they are also skeptical of the story, except our man has this irrefutable piece of evidence that no one can explain. In the end, almost as a throwaway, it is explained, leaving him completely baffled by the experience. And so are we, as readers, though it doesn't have the same urgency for us—it's merely mysterious, rarely uncanny. An unsolved mystery, as Robert Stack might say in his furry unmistakable voice. But it does work away on you a little. Did it even happen? Could our man the narrator somehow be simply mistaken? Or deluded? Most people dismiss it as a dream he had on the train ride, and perhaps it was. It's almost perfectly open-ended.

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Realms of Darkness, ed. Mary Danby (out of print)

Read story online.

The Big Book of the Masters of Horror, Weird and Supernatural Short Stories, pub. Dark Chaos

Realms of Darkness, ed. Mary Danby (out of print)

Read story online.

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Top 40

1. Sons of Kemet, "My Queen Is Harriet Tubman" (5:38)

2. Mac DeMarco, "On the Square" (3:29)

3. Tove Lo, "Glad He's Gone" (3:16)

4. Denzel Curry, "Ricky" (2:28)

5. Post Malone, "Goodbyes" (2:55)

6. Lizzo, "Truth Hurts" (2:53)

7. Anderson .Paak feat. Smokey Robinson, "Make It Better" (3:39)

8. Buzzy Bragg, "Rappin Duke & Friends (Extended Mix)" (6:10, 1986)

9. Jackie Brenston, "Rocket 88" (2:51, 1951)

10. Cecil Gant, "We're Gonna Rock" (2:16, 1950)

11. Bill Haley & His Comets, "Thirteen Women (And Only One Man in Town)" (2:52, 1954)

12. Bevis Frond, "Lights Are Changing" (4:55, 1988)

13. Elvis Presley, "The Girl of My Best Friend" (2:28, 1960)

14. Leadbelly, "Pick a Bale of Cotton" (2:59, 1940)

15. Pat Boone, "I'll Be Home" (3:00, 1956)

16. Jack Scott, "Goodbye Baby" (2:13, 1958)

17. Billy Fury, "Wondrous Place" (2:24, 1960)

18. Turbans, "When You Dance" (2:57, 1956)

19. Paul Anka, "Crazy Love" (2:26, 1958)

20. Steve Lawrence, "Footsteps" (2:13, 1960)

21. Honeycombs, "Eyes" (3:27, 1964)

22. Crystals, "No One Ever Tells You" (2:19, 1962)

23. Cookies, "I Never Dreamed" (2:37, 1964)

24. Peter and Gordon, "A World Without Love" (2:41, 1964)

25. Billy J. Kramer With the Dakotas, "Bad to Me" (2:18, 1963)

26. Beatles, "I'll Be Back" (2:24, 1964)

27. Searchers, "When You Walk in the Room" (2:22, 1964)

28. Them, "Mystic Eyes" (2:43, 1965)

29. Gene Pitney, "That Girl Belongs to Yesterday" (2:45, 1964)

30. Barbara Lewis, "Hello Stranger" (2:44, 1963)

31. Bob Dylan, "Like a Rolling Stone" (6:11, 1965)

32. Scott Walker, "Montague Terrace (In Blue)" (3:31, 1967)

33. Lovin' Spoonful, "Rain on the Roof" (2:11, 1966)

34. Gary Lewis & the Playboys, "She's Just My Style" (3:11, 1965)

35. Barbara McNair, "Baby A Go-Go" (2:49, 1965)

36. Beach Boys, "Good Vibrations" (3:36, 1966)

37. Rolling Stones, "Lady Jane" (3:08, 1966)

38. 4 Seasons, "Walk Like a Man" (2:17, 1963)

39. Beach Boys, "Girls on the Beach" (2:27, 1964)

40. Megan Thee Stallion feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, "Hot Girl Summer" (3:19)

THANKS: Billboard, Spin, Skip D. Expense, social media ... 9-11, 13-39, Bob Stanley, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!

2. Mac DeMarco, "On the Square" (3:29)

3. Tove Lo, "Glad He's Gone" (3:16)

4. Denzel Curry, "Ricky" (2:28)

5. Post Malone, "Goodbyes" (2:55)

6. Lizzo, "Truth Hurts" (2:53)

7. Anderson .Paak feat. Smokey Robinson, "Make It Better" (3:39)

8. Buzzy Bragg, "Rappin Duke & Friends (Extended Mix)" (6:10, 1986)

9. Jackie Brenston, "Rocket 88" (2:51, 1951)

10. Cecil Gant, "We're Gonna Rock" (2:16, 1950)

11. Bill Haley & His Comets, "Thirteen Women (And Only One Man in Town)" (2:52, 1954)

12. Bevis Frond, "Lights Are Changing" (4:55, 1988)

13. Elvis Presley, "The Girl of My Best Friend" (2:28, 1960)

14. Leadbelly, "Pick a Bale of Cotton" (2:59, 1940)

15. Pat Boone, "I'll Be Home" (3:00, 1956)

16. Jack Scott, "Goodbye Baby" (2:13, 1958)

17. Billy Fury, "Wondrous Place" (2:24, 1960)

18. Turbans, "When You Dance" (2:57, 1956)

19. Paul Anka, "Crazy Love" (2:26, 1958)

20. Steve Lawrence, "Footsteps" (2:13, 1960)

21. Honeycombs, "Eyes" (3:27, 1964)

22. Crystals, "No One Ever Tells You" (2:19, 1962)

23. Cookies, "I Never Dreamed" (2:37, 1964)

24. Peter and Gordon, "A World Without Love" (2:41, 1964)

25. Billy J. Kramer With the Dakotas, "Bad to Me" (2:18, 1963)

26. Beatles, "I'll Be Back" (2:24, 1964)

27. Searchers, "When You Walk in the Room" (2:22, 1964)

28. Them, "Mystic Eyes" (2:43, 1965)

29. Gene Pitney, "That Girl Belongs to Yesterday" (2:45, 1964)

30. Barbara Lewis, "Hello Stranger" (2:44, 1963)

31. Bob Dylan, "Like a Rolling Stone" (6:11, 1965)

32. Scott Walker, "Montague Terrace (In Blue)" (3:31, 1967)

33. Lovin' Spoonful, "Rain on the Roof" (2:11, 1966)

34. Gary Lewis & the Playboys, "She's Just My Style" (3:11, 1965)

35. Barbara McNair, "Baby A Go-Go" (2:49, 1965)

36. Beach Boys, "Good Vibrations" (3:36, 1966)

37. Rolling Stones, "Lady Jane" (3:08, 1966)

38. 4 Seasons, "Walk Like a Man" (2:17, 1963)

39. Beach Boys, "Girls on the Beach" (2:27, 1964)

40. Megan Thee Stallion feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, "Hot Girl Summer" (3:19)

THANKS: Billboard, Spin, Skip D. Expense, social media ... 9-11, 13-39, Bob Stanley, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!

Sunday, December 08, 2019

The Good Soldier (1915)

I'm happy the Modern Library list of best 20th-century novels put this Ford Madox Ford in my way (just as I'm slightly annoyed the list also includes another Ford title, Parade’s End, which is actually four novels). I like Englishman Ford’s intention to write "the finest French novel in the English language" (later he would compare it to Ulysses as examples of European in English). The refractions and circumlocutions are always on point, though that also makes it a little demanding, plus it features an early example of the unreliable narrator. That's John Dowell but his name is only mentioned a few times in the narrative—he's thus close to being an early example of the unnamed narrator too. Not knowing much about Ford or this novel I had always assumed it was some sort of war story. Ford wanted to call it The Saddest Story, which suits the story, the tone, and the narrator much better and is the title I wish they would use now. But World War I was going on and the publisher didn't want to hear from people with much sadder stories. I suppose it is a war story, in a way, but it's marital warfare rather than military. It's literary, distanced, and ironic, a story of two marriages and all the entanglements of the four principals. One couple is American and the other British. Edward Ashburnham, the Englishman, is a former soldier and now a philanderer of a certain type, that is, the type who falls lugubriously in love with his serial paramours. One of his lovers is our narrator's own wife, an affair of which the narrator claims ignorance. What feels most French to me about The Good Soldier is the way it unmoors itself from linear time, as Dowell broods and ruminates over his sad story. In time, all of Edward's affairs are detailed (as the nominal "good soldier"), along with his wife Leonora's strategies for coping with her strange beastly tormented husband, who is otherwise all kindness. The great strengths of this novel are the structure and the language. It may feel discursive and rambling at points but it tells a story that has a deceptive complexity, almost losing itself down the byways, but always coming back right again, maintaining an astonishing poise. As for the language, Dowell's voice is engaging and charming, using repetitions and ingenious comparisons that are unexpected, surprisingly apt, and often delightful, e.g., "two noble natures, drifting down life like fireships afloat on a lagoon," or eyes "as blue as the sides of a certain type of box of matches," or something that "glimmered under the tall trees of the dark park like a phosphorescent fish in a cupboard." It's a great novel, immersive for its brevity but also still quite strange and fascinating.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, December 06, 2019

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

USA, 45 minutes

Director: Buster Keaton

Writers: Jean C. Havez, Joseph A. Mitchell, Clyde Bruckman

Photography: Byron Houck, Elgin Lessley

Editors: Roy B. Yokelson, Buster Keaton

Cast: Buster Keaton, Kathryn McGuire, Ward Crane, Joe Keaton, Erwin Connelly

Buster Keaton's parody of both detective fiction and romance movies of the era finds him in good form. What is this Buster Keaton thing? Something about his very face and posture is somehow funny over and over—the stoic fool who never gives up hope. His strings are pulled by the movie magician stunt man who will try anything: fake mustaches everywhere you look, a banana peel gag (likely old even in 1924), poolroom trick shots in the service of proto-Hitchcockian suspense. He makes us think a doorway is a mirror and then that a doorway is a vault (a portrait of George Washington looks askance at the deception). He leaps through a window and into a dress and shortly after that he leaps through the body of his accomplice and a wall behind. It's impossible, don't you see, a special effect. He does these things because he can. His character, Sherlock Jr., is pure confidence in the breach, absurdly swaggering in top hat and tails. That confidence may bend but it is never broken. He is a nitwit, of course. Our man is actually a film projector who only dreams of becoming a detective. Most of the movie takes place as a movie-within-a-movie dream, which features him stepping in and out of the screen of the romance movie Hearts and Pearls, or The Lounge Lizard's Lost Love, which is playing at the movie theater where he works. Our point of view is from the seats in the audience (Woody Allen lifted and paid homage to it 60 years later in The Purple Rose of Cairo). At first, because the gag is about all the places he keeps finding himself with the cuts in the movie-within-a-movie, the movie-within-a-movie briefly no longer makes sense, roaming for no apparent reason from cliffsides to African jungle with lions and so forth. Soon enough it remembers itself. The dry and gently acerbic tone of the whole thing is captured in an intertitle: "By the next day the mastermind had completely solved the mystery—with the exception of locating the pearls and finding the thief." The best is saved for last, as Buster Keaton was a filmmaker who always knew what he was doing, and more so in his prime. A spectacular and often very funny chase scene with a motorcycle and cars and many stunts is set in motion by a signature grand stunt, vaulting off a second-story rooftop into a moving automobile using a railroad crossing guard (somehow the driver never notices). No doubt Keaton really did it and lots of other stuff here too—he spent months learning the pool shots, for example. He was like that. That stone face tells everything and nothing.

Director: Buster Keaton

Writers: Jean C. Havez, Joseph A. Mitchell, Clyde Bruckman

Photography: Byron Houck, Elgin Lessley

Editors: Roy B. Yokelson, Buster Keaton

Cast: Buster Keaton, Kathryn McGuire, Ward Crane, Joe Keaton, Erwin Connelly

Buster Keaton's parody of both detective fiction and romance movies of the era finds him in good form. What is this Buster Keaton thing? Something about his very face and posture is somehow funny over and over—the stoic fool who never gives up hope. His strings are pulled by the movie magician stunt man who will try anything: fake mustaches everywhere you look, a banana peel gag (likely old even in 1924), poolroom trick shots in the service of proto-Hitchcockian suspense. He makes us think a doorway is a mirror and then that a doorway is a vault (a portrait of George Washington looks askance at the deception). He leaps through a window and into a dress and shortly after that he leaps through the body of his accomplice and a wall behind. It's impossible, don't you see, a special effect. He does these things because he can. His character, Sherlock Jr., is pure confidence in the breach, absurdly swaggering in top hat and tails. That confidence may bend but it is never broken. He is a nitwit, of course. Our man is actually a film projector who only dreams of becoming a detective. Most of the movie takes place as a movie-within-a-movie dream, which features him stepping in and out of the screen of the romance movie Hearts and Pearls, or The Lounge Lizard's Lost Love, which is playing at the movie theater where he works. Our point of view is from the seats in the audience (Woody Allen lifted and paid homage to it 60 years later in The Purple Rose of Cairo). At first, because the gag is about all the places he keeps finding himself with the cuts in the movie-within-a-movie, the movie-within-a-movie briefly no longer makes sense, roaming for no apparent reason from cliffsides to African jungle with lions and so forth. Soon enough it remembers itself. The dry and gently acerbic tone of the whole thing is captured in an intertitle: "By the next day the mastermind had completely solved the mystery—with the exception of locating the pearls and finding the thief." The best is saved for last, as Buster Keaton was a filmmaker who always knew what he was doing, and more so in his prime. A spectacular and often very funny chase scene with a motorcycle and cars and many stunts is set in motion by a signature grand stunt, vaulting off a second-story rooftop into a moving automobile using a railroad crossing guard (somehow the driver never notices). No doubt Keaton really did it and lots of other stuff here too—he spent months learning the pool shots, for example. He was like that. That stone face tells everything and nothing.

Sunday, December 01, 2019

Norman Mailer: A Double Life (2013)

There were already at least four biographies of Norman Mailer when J. Michael Lennon's brick was published in 2013. I'm not sure why it's the one I grabbed but generally by the reviews I seem to have made the right choice. It is detailed and exhaustive, covering every step of Mailer's professional development, from The Naked and the Dead in 1948 to The Castle in the Forest in 2007. Lennon was a friend and colleague of Mailer and his huge family, which probably makes him the "authorized" biographer. He is more kind, or politic, than I would be on some of Mailer's work (notably The Prisoner of Sex and maybe Ancient Evenings). But he also attempts to imbibe the Mailer spirit and let the chips fall where they may on some of the ugliest chapters, such as Mailer stabbing his second wife (a crime that would have sent many to prison) or his judgment vouching for the parole of Jack Abbott. Mostly I appreciated getting the stories more or less straight. I feel confident I could pass a test now on who each of his six wives were, though I'm probably still muddled on which of the nine kids belongs to whom. I'm envious of his support too—his greatest fan, from inside the womb, was his doting mother. It's such an improbable life in many ways. He studied engineering in college but already wanted to be a great American novelist. He tried to get out of being drafted but decided war experience would be good for his literary career—and it was. Mailer and James Jones are generally credited with writing the "great" American novels about World War II—conventional in many ways, but big and sprawling and ambitious. Jones never tinkered much with his impulses to churn out massive pulpy narratives, but Mailer went around the bend a few different ways, eventually arriving, 30 years later, with The Executioner's Song, back at writing very big books—but now with virtually all the pulp extruded. Jones never came close to the place. Lennon's title means all kinds of things—the double portion of vitality Mailer seemed to have, his lifetime of philandering (well detailed here, speaking of delicious pulp—he had sex with Gloria Steinem!), and his theology / cosmology in which he believes every person bears two conflicting persons at war in a single body. Beyond that an intriguing vision that God is not omnipotent and is engaged in a deadly war with Satan. Mailer's case for faith is thus that God needs all the help he can get. On the other hand it does make some intuitive sense and explains a lot about what we can see in the world and church. I think one of Lennon's ambitions is to restore that side of Mailer's work to credibility. It was often ignored, or laughed at and treated as a joke. Lennon's biography is so thorough and answers so many questions about Mailer, he's entitled to advocate for what he likes. If you have any interest in Mailer it's also fun to read.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)