UK, 94 minutes

Director: Danny Boyle

Writers: Irvine Welsh, John Hodge

Photography: Brian Tufano

Editor: Masahiro Hirakubo

Cast: Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Kevin McKidd, Robert Carlyle, Kelly Macdonald, Peter Mullan, Irvine Welsh, Susan Vidler, Pauline Lynch

I'm not normally one to use dictionary definitions as an opening, but in this case it's reasonably useful. Thus, "trainspotting," according to Dictionary.com's 21st Century Lexicon: "n., the hobby of watching trains and noting their serial numbers, usu. for long periods of time; by extension, any hobby or obsession with a trivial pursuit." Trainspotting is not a movie about jotting down serial numbers of passing trains. The "hobby or obsession with a trivial pursuit" under the glass here is the acquisition and use of heroin. Why? As our humble narrator Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor), a citizen of Edinburgh, Scotland, acknowledges early, after charting routes to that particular choice, "Who needs reasons when you've got heroin?"

As one of the great drug movies, Trainspotting is particularly good at the extremes—swiftly homing in on precise and persuasive reasons people use heroin, and doing that so effectively you might as well plan on a short period of wanting a hit yourself. And then of course there are the nightmare ends. Along the way it careens wildly, from unfortunate gross-out fest (at least one too many scenes involving human feces) to dazzling turns of fantasy to sublime soundtrack movie to deceptively casual morality plays embedded within a narrative arc borrowed from A Clockwork Orange and Drugstore Cowboy, where the people we like best start out bad, turn good, and then go bad again. Along the way it's all trainspotting: getting, using, and getting again, or as Renton says: "Pile misery upon misery, heap it up on a spoon and dissolve it with a drop of bile, then squirt it into a stinking, purulent vein, and do it all over again ... propelling ourselves with longing toward the day that it would all go wrong."

Friday, August 31, 2012

Trainspotting (1996)

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

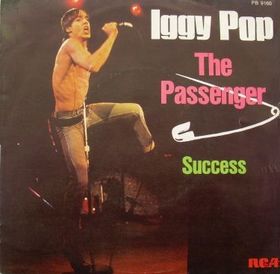

Iggy Pop, "Success" (1977)

(listen)

This was the single (b/w "The Passenger") from the Lust for Life album, Iggy's second Bowie collaboration that year. If it's pretty clearly a case of comical wish fantasy to pick this for the radio—"Here comes success, over my hill ... here comes my car ... my Chinese rug"—it always did jump right off the album for its hilarious high spirits. It is a laugher, literally, and perhaps the point where the heavy-stomping exuberance of the album reaches its finest point. All these tracks, especially this, feel a lot more like Iggy music, slashing riffs and bellowing chants and the brothers Tony and Hunt Sales (sons of Soupy) hammering down the rhythm section with a good deal of power. It contrasts well with the doomy moody swoons of The Idiot, which are fine enough but feel more like Bowie music to me. "Success" is a great example of one of the best features of this session, when Iggy starts taking it off the top of his head in a call and response structure, finally reaching a point where he is improvising at the top of his lungs, with the chorus, chiefed by Bowie, sending it right back with dispatch, until they all crack up and almost certainly must have fallen about the place. Freeze frame. Golden memory. Now that "Lust for Life" is the better-known rocker, thanks to sports enthusiasts and/or the movie Trainspotting, that has become the better-known "choose life" option, and indeed, perhaps the better rocker too. But on this album, they are all pretty good rockers. And I haven't yet begun to get over the priceless moment at the end of "Success": "I'm gonna do the twist ... I'm gonna hop like a frog ... I'm gonna go out in the street and do anything I want ... oh shit!"

This was the single (b/w "The Passenger") from the Lust for Life album, Iggy's second Bowie collaboration that year. If it's pretty clearly a case of comical wish fantasy to pick this for the radio—"Here comes success, over my hill ... here comes my car ... my Chinese rug"—it always did jump right off the album for its hilarious high spirits. It is a laugher, literally, and perhaps the point where the heavy-stomping exuberance of the album reaches its finest point. All these tracks, especially this, feel a lot more like Iggy music, slashing riffs and bellowing chants and the brothers Tony and Hunt Sales (sons of Soupy) hammering down the rhythm section with a good deal of power. It contrasts well with the doomy moody swoons of The Idiot, which are fine enough but feel more like Bowie music to me. "Success" is a great example of one of the best features of this session, when Iggy starts taking it off the top of his head in a call and response structure, finally reaching a point where he is improvising at the top of his lungs, with the chorus, chiefed by Bowie, sending it right back with dispatch, until they all crack up and almost certainly must have fallen about the place. Freeze frame. Golden memory. Now that "Lust for Life" is the better-known rocker, thanks to sports enthusiasts and/or the movie Trainspotting, that has become the better-known "choose life" option, and indeed, perhaps the better rocker too. But on this album, they are all pretty good rockers. And I haven't yet begun to get over the priceless moment at the end of "Success": "I'm gonna do the twist ... I'm gonna hop like a frog ... I'm gonna go out in the street and do anything I want ... oh shit!"

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

#20: The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941)

In many ways The Maltese Falcon arrives now full-blown, with a lot of its sure-fire elements in tow: a great cast, a great screenplay based on a great literary property, a great strategy for production design and photography (yes, Phil's kids, black and white), and a great director in John Huston, who remained as vital (and as hit and miss) right into the '80s. But none of this was so certain in its time. Huston was no sure thing in his first effort as a director (the shot earned on the basis of his work as a screenplay writer), nor was Humphrey Bogart quite yet the star he would become.

As is typical of most hard-boiled detective fiction in the classic mode—and, based on one of Dashiell Hammett's best and best-known novels, this is about as classic as it gets—the plot developments come fast and furious, quickly snarling into a mess verging on chaos, albeit calmly piloted by the private eye at the center of it, in this case Bogart's Sam Spade. For the most part The Maltese Falcon sticks close to the book, particularly its dialogue, but Huston's screenplay makes it look a lot easier than it probably is to adapt one of these stories, and it remains the standard by which to compare others.

In many ways The Maltese Falcon arrives now full-blown, with a lot of its sure-fire elements in tow: a great cast, a great screenplay based on a great literary property, a great strategy for production design and photography (yes, Phil's kids, black and white), and a great director in John Huston, who remained as vital (and as hit and miss) right into the '80s. But none of this was so certain in its time. Huston was no sure thing in his first effort as a director (the shot earned on the basis of his work as a screenplay writer), nor was Humphrey Bogart quite yet the star he would become.

As is typical of most hard-boiled detective fiction in the classic mode—and, based on one of Dashiell Hammett's best and best-known novels, this is about as classic as it gets—the plot developments come fast and furious, quickly snarling into a mess verging on chaos, albeit calmly piloted by the private eye at the center of it, in this case Bogart's Sam Spade. For the most part The Maltese Falcon sticks close to the book, particularly its dialogue, but Huston's screenplay makes it look a lot easier than it probably is to adapt one of these stories, and it remains the standard by which to compare others.

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Twentynine Palms: A True Story of Murder, Marines, and the Mojave (2002)

This is one of those true crime books that seem to want the pathos of the socioeconomic circumstances to do most of the heavy lifting, along with massive infusions of heightened language. It almost works, partly because it focuses so unapologetically on the American underclass and the details of their lives the rest of us would rather not know, but mostly because of the bleak Mojave Desert setting in a town dependent on a nearby Marine base. In 1991, two girls—one 21, the other just one day short of her 16th birthday—are raped, stabbed 33 times apiece, and left to die in the older girl's apartment. The crime is committed by a Marine with a history of bad behavior. He is caught and put away—it takes some time, but the reasons have less to do with systemic corruption, military and otherwise, and more to do with systemic grinding poverty. There's little question they got the right man. Sadly, there's also little question that the lost lives don't matter much, which is the greater tragedy here. Deanne Stillman runs down the family history of the younger girl over a few generations and it's all domestic abuse, early pregnancies, prostitution, and/or alcoholism. It's horrific in its predictability, especially the abuse. It's just expected that boyfriends will beat girlfriends, husbands will beat wives. The only questions are when it will start and how severe it will become. Stillman thus doesn't have that much to work with—the article on which the book is based is probably better. There's an awful lot of larding up going on here as Stillman attempts to blow up the impact of this into something more than it is. It might make an interesting movie because of its setting—maybe it's already been done? (I'm not seeing evidence of it.) Full disclosure: I have little sympathy for flag-waving patriotism, particularly among the underclass, even understanding they often have little other good choice. Debie McMaster, the mother of one of the victims here, started to lose me when it's revealed in her biography that she turned up at anti-Vietnam War demonstrations to hassle the protesters. But that's just me. As lugubriously as Stillman may do so, I suspect she has given a well-rounded, complete, and eminently fair portrait of the people she encountered working on this story.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Stick to Me (1977)

It's probably going too far to say this represents a shadow of a lost album but it's still an interesting story. With some buzz at their backs from the first two albums of the year before, Graham Parker and the Rumour toured a bunch and then retreated to the studio to lay down the third album before embarking on more touring. A lot of work went into it, it sounds like—string sections, a high concept for a long psychedelic soul song, and all the usual angsty blood, sweat, and tears, which I suspect is more than most people (me included) generally know to get an album in the can. Then, all finished, something turned out to be wrong with the master tape, and suddenly it was all lost. They had literally one week before they were set to travel. They went back to the studio. Nick Lowe presided over the board and the band pounded through the set, treating it necessarily more like live performance than whatever it was they had worked out before. For me, only dimly aware of the story, it was the first Graham Parker album I heard and it just lit me up. It was easily my favorite until I checked out the first two and discovered Heat Treatment. Once I knew the Stick to Me story I could hear the rushed quality of it, from which "The Heat in Harlem," the stab at psychedelic soul, clearly suffers most. I don't know that it ever had enough in it to compete seriously with "Time Has Come Today" (long version) but I do wish I could hear the original to judge. Otherwise I think the circumstances may have actually served the session well, contributing to what makes it so good, however unpleasant it must have been for the players at the time. The music is irresistible, spry and quick to make its points, but with an impatient edge, restless, constantly prowling and moving and hitting sweet spots on practically every track. I like the way it retreats to the Muscle Shoals soul moves they have so fully absorbed. I like the way it entertains romantic American migratory history ("Soul on Ice," "The New York Shuffle," "The Heat in Harlem," "The Raid")—the fascination for some heroic American vision is so ingenuous it's adorable, and perfectly winning. And I will say this about "The Heat in Harlem"—it fails for me, as too long though not altogether wearing out its welcome, only when I start to think about it too much. Otherwise it's all of a piece from when I was first infatuated with the album. It had me at the needle drop and the roaring title song, which takes off like a jet and drags everything else behind it, supersonic style. Both sides good.

Friday, August 24, 2012

There Will Be Blood (2007)

USA, 158 minutes

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Writers: Paul Thomas Anderson, Upton Sinclair

Photography: Robert Elswit

Music: Jonny Greenwood

Editor: Dylan Tichenor

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Dano, Kevin J. O'Connor, Ciaran Hinds, Dillon Freasier, Russell Harvard, David Warshofsky, Colton Woodward

With his third movie in 10 years just around the corner (The Master), it's evident that director/screenwriter Paul Thomas Anderson has slowed his output considerably since his first three, which came out in nearly as many years. By contrast, a gulf of five years exists on either side of There Will Be Blood. Maybe it needs that much room to breathe, this huge, baffling, enthralling, exasperating, stunningly beautiful, and ultimately satisfying story of the greed and corruption of the spirit that accompanied the early days of oil exploration and the oil business in the early 20th century. It is way beyond the ordinary plodding costume earnestness of historical pictures, or the naturalism that the source material from muckraker Upton Sinclair would seem to suggest. It doesn't even have that much to do specifically with the oil industry as such.

It is rather a movie about a personality conflict, between self-described oilman Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) on the one hand and self-described "tender of his Father's flock" Eli Sunday (Paul Dano) on the other, with an illustrative side story about a visit by Plainview's self-described long-lost half-brother Henry (Kevin J. O'Connor). Whether or not Anderson intended it, I have come to take the picture almost purely on allegorical levels. That makes the personality conflict at its heart essentially a battle of Rapacious Capitalism and Infantilizing Religiosity (with Henry stepping in as Last Chance for Humanity). They are, of course, arguably the primary motivating forces that competed across the canvas of the 20th century for world domination, or barring that anyway the American soul at least. The surprise for me is that it works at all, let alone as well as it does. And speaking of surprises, please note: spoilers discussed with abandon beyond the jump.

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Writers: Paul Thomas Anderson, Upton Sinclair

Photography: Robert Elswit

Music: Jonny Greenwood

Editor: Dylan Tichenor

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Dano, Kevin J. O'Connor, Ciaran Hinds, Dillon Freasier, Russell Harvard, David Warshofsky, Colton Woodward

With his third movie in 10 years just around the corner (The Master), it's evident that director/screenwriter Paul Thomas Anderson has slowed his output considerably since his first three, which came out in nearly as many years. By contrast, a gulf of five years exists on either side of There Will Be Blood. Maybe it needs that much room to breathe, this huge, baffling, enthralling, exasperating, stunningly beautiful, and ultimately satisfying story of the greed and corruption of the spirit that accompanied the early days of oil exploration and the oil business in the early 20th century. It is way beyond the ordinary plodding costume earnestness of historical pictures, or the naturalism that the source material from muckraker Upton Sinclair would seem to suggest. It doesn't even have that much to do specifically with the oil industry as such.

It is rather a movie about a personality conflict, between self-described oilman Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) on the one hand and self-described "tender of his Father's flock" Eli Sunday (Paul Dano) on the other, with an illustrative side story about a visit by Plainview's self-described long-lost half-brother Henry (Kevin J. O'Connor). Whether or not Anderson intended it, I have come to take the picture almost purely on allegorical levels. That makes the personality conflict at its heart essentially a battle of Rapacious Capitalism and Infantilizing Religiosity (with Henry stepping in as Last Chance for Humanity). They are, of course, arguably the primary motivating forces that competed across the canvas of the 20th century for world domination, or barring that anyway the American soul at least. The surprise for me is that it works at all, let alone as well as it does. And speaking of surprises, please note: spoilers discussed with abandon beyond the jump.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Replacements, "Kiss Me On the Bus" (1985)

(listen)

For someone who spent a lot of time projecting a world-weary and wizened cynicism, the Replacements' Paul Westerberg was actually, and not so secretly, a puppy dog running circles at one's feet, begging for a treat (or a drink, if you don't want to pound the metaphor too hard). The breakthrough album Let it Be was full of such gestures, and so was the follow-up, 1985's Tim (produced by Tommy Ramone), which neatly consolidated all the advances of their first five years. Bob Stinson was still on hand, and in fact this is one of the best periods for the band. A show I saw in Seattle in late 1985 was absolutely transporting, one of the best by them I ever saw, and I'm pretty sure this larky little love song was part of that long set, as I was waiting for it and nothing about that night disappointed me. One of the best features of "Kiss Me on the Bus" is that it works loud and raw and also at softer, gentler volumes, where the playfulness of the whole scene emerges. It seems to be the kind of idle fantasy one indulges when packed with strangers, as on public transit. Or maybe, less likely, he's riding with a girlfriend and wallowing in the pure pleasure of being with her, playing his part in the obnoxious "shmoopy shmoopy" beeswax of those freshly in love. Whatever it is, it's also a perfectly lovely moment, innocent and carefree, in both conception and execution. Stinson's solo at the break is one of his best—nimble, lyrical, frothy with pub-rock, and done so quickly that it almost invisibly propels the momentum more intensely. "Smooth move, Ex-Lax." At just about three minutes even, this one is very hard to beat.

For someone who spent a lot of time projecting a world-weary and wizened cynicism, the Replacements' Paul Westerberg was actually, and not so secretly, a puppy dog running circles at one's feet, begging for a treat (or a drink, if you don't want to pound the metaphor too hard). The breakthrough album Let it Be was full of such gestures, and so was the follow-up, 1985's Tim (produced by Tommy Ramone), which neatly consolidated all the advances of their first five years. Bob Stinson was still on hand, and in fact this is one of the best periods for the band. A show I saw in Seattle in late 1985 was absolutely transporting, one of the best by them I ever saw, and I'm pretty sure this larky little love song was part of that long set, as I was waiting for it and nothing about that night disappointed me. One of the best features of "Kiss Me on the Bus" is that it works loud and raw and also at softer, gentler volumes, where the playfulness of the whole scene emerges. It seems to be the kind of idle fantasy one indulges when packed with strangers, as on public transit. Or maybe, less likely, he's riding with a girlfriend and wallowing in the pure pleasure of being with her, playing his part in the obnoxious "shmoopy shmoopy" beeswax of those freshly in love. Whatever it is, it's also a perfectly lovely moment, innocent and carefree, in both conception and execution. Stinson's solo at the break is one of his best—nimble, lyrical, frothy with pub-rock, and done so quickly that it almost invisibly propels the momentum more intensely. "Smooth move, Ex-Lax." At just about three minutes even, this one is very hard to beat.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Capturing the Friedmans (2003)

#21: Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003)

As we embark on our top 20s, it's probably as good a place as any to rendezvous on documentary picks, and also to acknowledge the growing burden on what's to come of a widely accepted film canon—as Steven puts it, "when I hear 'favorite' I am inexorably drawn to 'best.'" That's an understandable impulse, but equally so, at least for me, is the contrarian one to push against exactly that. I have been making a project the past few years of going through the movies listed at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? (link below), the carefully calibrated inventory, updated annually, of the critical consensus greatest of the greatest. It currently starts Citizen Kane, Vertigo, The Rules of the Game, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The Godfather. You get the idea.

It's interesting what a range of reaction I have to them, almost certainly distorted by the pressure that inevitably accompanies the very idea of "best." Some I love (they are ahead on my list, or previously mentioned), some I don't much care for even as I grudgingly allow their attractions (The Searchers, Battleship Potemkin, La Dolce Vita), and many more, like The Rules of the Game, I am mostly indifferent to. (One, The Passion of Joan of Arc, was sacrificed to make room for this—I'm happy for the opportunity because, shortly after Steven named Hoop Dreams back in the 40s, I was surprised to realize I didn't have even one documentary on my list.) A good many of my picks still to come probably fall more in the category of "favorites," and indeed one of my key criteria has been how often I've seen something. If I've seen one picture six times and another twice, the one I've been drawn to more often gets the edge in rankings. It's more self-evidently a favorite, no matter how far out of the critical mainstream it may be. I'm trying as hard as I can simply to let "best" take care of itself.

As we embark on our top 20s, it's probably as good a place as any to rendezvous on documentary picks, and also to acknowledge the growing burden on what's to come of a widely accepted film canon—as Steven puts it, "when I hear 'favorite' I am inexorably drawn to 'best.'" That's an understandable impulse, but equally so, at least for me, is the contrarian one to push against exactly that. I have been making a project the past few years of going through the movies listed at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? (link below), the carefully calibrated inventory, updated annually, of the critical consensus greatest of the greatest. It currently starts Citizen Kane, Vertigo, The Rules of the Game, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The Godfather. You get the idea.

It's interesting what a range of reaction I have to them, almost certainly distorted by the pressure that inevitably accompanies the very idea of "best." Some I love (they are ahead on my list, or previously mentioned), some I don't much care for even as I grudgingly allow their attractions (The Searchers, Battleship Potemkin, La Dolce Vita), and many more, like The Rules of the Game, I am mostly indifferent to. (One, The Passion of Joan of Arc, was sacrificed to make room for this—I'm happy for the opportunity because, shortly after Steven named Hoop Dreams back in the 40s, I was surprised to realize I didn't have even one documentary on my list.) A good many of my picks still to come probably fall more in the category of "favorites," and indeed one of my key criteria has been how often I've seen something. If I've seen one picture six times and another twice, the one I've been drawn to more often gets the edge in rankings. It's more self-evidently a favorite, no matter how far out of the critical mainstream it may be. I'm trying as hard as I can simply to let "best" take care of itself.

Sunday, August 19, 2012

Washington Square (1881)

Washington Square is a great example of Henry James's prodigious storytelling talent. It's in the vein of a comedy of manners and indeed is often funny, mostly by dint of the ninny Aunt Penniman. It's a tragedy as well, or at least contains unpleasant characters who do not necessarily receive their just desserts, which I suppose is not the same thing. It's arguable that the father, Dr. Austin Sloper, is possessed of a fatal flaw that dooms him, but for the most part he is serenely unaware of it, which is hardly satisfying. The story of love lost and found is irresistible for me—it often put me in mind of Jane Austen the way it plays out—and Catherine Sloper, the main character and our heroine, comes with layers of fascinating complexity, a James specialty. I've seen a Hollywood version of this with Olivia de Havilland and Montgomery Clift (called The Heiress) and it comes with a big wallop of an ending. The movie, which I saw first, is so generally faithful that I wondered as I was reading how James would handle such drama but I needn't have worried. The rebuke of Catherine by her father (and the lessons each takes from it), and then the resolution with her lover, were not nearly so highly contrasted by James, the better decision I think if one is comparing them. The satisfactions of the movie's broad gestures are replaced by a rueful complexity that is more ambiguous and open to conjecture as it stays in one's head and turns itself about. I tend to come down on the side of Catherine Sloper as a strong and self-possessed person who has come to know herself, and to appreciate herself and her lot for what they are. I have no doubt it's not difficult to make another case, closer to her father's view, that she is sad and pathetic, a lost soul. But no one can deny she is a great character of literature. I also really liked the early/mid-19th-century New York setting. Nice to see Europe mostly out of the picture for once with James, though of course the cultural relations between Europe and America remain one of the primary calling cards. But as James was born and mostly raised a New Yorker he brings a good deal of convincing sense of place here that feels more intimate than his European settings. Some of them are a little studied, occasionally even smacking of a guidebook. This is definitely one of my favorites by James.

"interlocutor" count = 2/157 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

"interlocutor" count = 2/157 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Heat Treatment (1976)

I'm not always sure about Graham Parker but I am always sure about this one, which I really, really like. Sometimes, often, I forget how good it is, and then I happen to play it again. The songs sound like pure stuff of life experience, unadorned and unpretentious, unbowed above all. Taking chances and constantly pulling it off. Example: "Black Honey," which is about as awkwardly unself-consciously racially odd as the title immediately suggests. It's not exactly PC, but it's not exactly not either. The ache in Parker's voice obviates everything except the unbelievable grace he applies. It's in my soul. That's what he sings—"Oh, black honey's in my soul"—and that's what the experience of hearing it feels like. It's remarkable what he does, covering great plains of emotional territory (and then following it with a song called "Hotel Chambermaid," another good one, they're all good ones). I am frankly surprised that Heat Treatment is generally considered comparable to its companion piece from the same year, Howlin' Wind, which admittedly is a pretty good first album, with Parker's destiny already half written: blowing up with punk-rock (but linked more directly to its immediate predecessor, pub-rock), angry, defiant, and got its chin out, tender/bruised style, and all wrapped up in a blaze of horn-driven Memphis soul stew straight outta the UK. Howlin' Wind is good but Heat Treatment is amazing, really. I have returned to it many times, surprised to find the same kick always there waiting for me. What is it? Something about the scrappy working-class manner, I guess—literally, I guess. Something about his singing. Something about the way he locks in with the band. I don't know why I love this, I just do. Parker would ultimately find his place in the New Wave angry-young-Brit rotation also occupied by Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, and others (even, a little, that saint of pure good nature, Nick Lowe). Parker's best stuff to me always has a certain edge of desperation that is not particularly fashionable and certainly not pretty. He sounds truly denied, and fighting back, and I respect that and take it as a model for living too. It just somehow gets me where I live. At least before the '80s, Parker seemed to have a genuine knack for how to use a whole rock band as an instrument, or maybe the Rumour just happened to play it that way because he and they could. This is a great meeting of artist and band, one of the best. You can go right down the line here, song by song. The whole thing barely lasts half an hour, with 10 songs. But they just really tear up the joint.

Friday, August 17, 2012

The Ice Storm (1997)

USA, 112 minutes

Director: Ang Lee

Writers: Rick Moody, James Schamus

Photography: Frederick Elmes

Music: Mychael Danna

Editor: Tim Squyres

Cast: Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Henry Czerny, Adam Hann-Byrd, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, Jamey Sheridan, Elijah Wood, Sigourney Weaver, Michael Cumpsty, Katie Holmes, Allison Janney, David Krumholtz

I thought The Ice Storm was the movie of the year even back in the day. I had become aware a little earlier of director Ang Lee, originally from Taiwan, with 1993's appealing romantic comedy The Wedding Banquet. He fast established himself as a director of protean ability and wide range with Sense and Sensibility, a decent Merchant/Ivory-style upholstered drama based on Jane Austen, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, a martial arts fantasy, and Brokeback Mountain, an epic romance about modern-day gay cowboys. The 2003 Hulk cemented all that, if it needed cementing, though that one has subsequently been dropped down the memory hole, perhaps for the best. I've never seen it.

The Ice Storm is, as advertised, an impressively detailed portrait of bad weather. On a Thanksgiving weekend, two middle-class American families of the '70s with generalized spiritual sickness are doing things that can't be undone, even as a terrible winter storm closes down on them. It's an ensemble piece, involving all eight people from the two families and many others as well, with lots of good players chipping in small, effective turns, delivering strong performances in a swimming sea of faces. I still remember and think of many of them—Joan Allen, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, even Sigourney Weaver and Elijah Wood—chiefly as they appear here.

Director: Ang Lee

Writers: Rick Moody, James Schamus

Photography: Frederick Elmes

Music: Mychael Danna

Editor: Tim Squyres

Cast: Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Henry Czerny, Adam Hann-Byrd, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, Jamey Sheridan, Elijah Wood, Sigourney Weaver, Michael Cumpsty, Katie Holmes, Allison Janney, David Krumholtz

I thought The Ice Storm was the movie of the year even back in the day. I had become aware a little earlier of director Ang Lee, originally from Taiwan, with 1993's appealing romantic comedy The Wedding Banquet. He fast established himself as a director of protean ability and wide range with Sense and Sensibility, a decent Merchant/Ivory-style upholstered drama based on Jane Austen, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, a martial arts fantasy, and Brokeback Mountain, an epic romance about modern-day gay cowboys. The 2003 Hulk cemented all that, if it needed cementing, though that one has subsequently been dropped down the memory hole, perhaps for the best. I've never seen it.

The Ice Storm is, as advertised, an impressively detailed portrait of bad weather. On a Thanksgiving weekend, two middle-class American families of the '70s with generalized spiritual sickness are doing things that can't be undone, even as a terrible winter storm closes down on them. It's an ensemble piece, involving all eight people from the two families and many others as well, with lots of good players chipping in small, effective turns, delivering strong performances in a swimming sea of faces. I still remember and think of many of them—Joan Allen, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, even Sigourney Weaver and Elijah Wood—chiefly as they appear here.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Beatles, "Act Naturally" (1965)

(listen)

This is another Beatles charmer from the mid-'60s, a Buck Owens cover—his first #1 on the country charts, in fact—which the lads in their blithely winning manner turn into a nice little vehicle for Ringo. An absolutely perfect one, as it happens. Twangy guitar and all he has to do is ... act naturally. It was the flip of "Yesterday," and as far as I'm concerned that song needed one. And it got one. In this. They road-tested it on Ed Sullivan in 1965, saw it was good, and so it was. I think it really does bring out all that earthbound teddy bear charm of Ringo, the oldest Beatle, the cult drummer, the sad sack face and the steady tidy hand at the drum kit. There was never anything fancy about him, and there's nothing fancy about this song (I mentioned it was a Buck Owens cover, didn't I?) and that's exactly what I love about it. All we have to do is all we have to sing is: act naturally. Because, as always, I am amazed at the way this band had with a song to get in and do their job so efficiently and leave, I will also mention that I have this clocking in at about 2:33. Like this: "They're gonna put me in the movies / They're gonna make a big star out of me / We'll make a film about a man that's sad and lonely /And all I have to do is act naturally." I don't even know what else there is to say. This is just so fine. Huzzah! Again!

This is another Beatles charmer from the mid-'60s, a Buck Owens cover—his first #1 on the country charts, in fact—which the lads in their blithely winning manner turn into a nice little vehicle for Ringo. An absolutely perfect one, as it happens. Twangy guitar and all he has to do is ... act naturally. It was the flip of "Yesterday," and as far as I'm concerned that song needed one. And it got one. In this. They road-tested it on Ed Sullivan in 1965, saw it was good, and so it was. I think it really does bring out all that earthbound teddy bear charm of Ringo, the oldest Beatle, the cult drummer, the sad sack face and the steady tidy hand at the drum kit. There was never anything fancy about him, and there's nothing fancy about this song (I mentioned it was a Buck Owens cover, didn't I?) and that's exactly what I love about it. All we have to do is all we have to sing is: act naturally. Because, as always, I am amazed at the way this band had with a song to get in and do their job so efficiently and leave, I will also mention that I have this clocking in at about 2:33. Like this: "They're gonna put me in the movies / They're gonna make a big star out of me / We'll make a film about a man that's sad and lonely /And all I have to do is act naturally." I don't even know what else there is to say. This is just so fine. Huzzah! Again!

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

The Graduate (1967)

#22: The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967)

Picking up where Phil recently left Benjamin Braddock to his scuba gear, I have been living with The Graduate one way or another for most of my life—sometimes taking it as straight-up farce, sometimes as sophisticated and urbane, sometimes as statement for a generation, sometimes not connecting with it at all ("too clever, too patronizing, and ultimately too glib to be taken seriously," as Phil interprets it), sometimes wanting to jump up and down with the pure joy of its accomplishment. In short, it seems to work for me like the old saw about not being able to step in the same river twice. It's always different from the way I remember it, there's almost always something I hadn't noticed before, and watching it again is never the same experience twice.

Mostly it's a comedy of manners, a spoof on the shallow values of the conformist/materialist '50s colliding with the self-conscious, only vaguely hip sexual liberation of the post-birth-control '60s. But even as it plays as a comedy—and as a comedy it sparkles—its center of gravity remains a black hole of dread, around which all the players are orbiting and into which they are all slowly, without exception, collapsing.

Picking up where Phil recently left Benjamin Braddock to his scuba gear, I have been living with The Graduate one way or another for most of my life—sometimes taking it as straight-up farce, sometimes as sophisticated and urbane, sometimes as statement for a generation, sometimes not connecting with it at all ("too clever, too patronizing, and ultimately too glib to be taken seriously," as Phil interprets it), sometimes wanting to jump up and down with the pure joy of its accomplishment. In short, it seems to work for me like the old saw about not being able to step in the same river twice. It's always different from the way I remember it, there's almost always something I hadn't noticed before, and watching it again is never the same experience twice.

Mostly it's a comedy of manners, a spoof on the shallow values of the conformist/materialist '50s colliding with the self-conscious, only vaguely hip sexual liberation of the post-birth-control '60s. But even as it plays as a comedy—and as a comedy it sparkles—its center of gravity remains a black hole of dread, around which all the players are orbiting and into which they are all slowly, without exception, collapsing.

Sunday, August 12, 2012

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2005)

In the original Swedish, the title of this first and best-known crime novel in Stieg Larsson's wildly popular "Millennium" trilogy translates as the rather stark Men Who Hate Women. It says many things at once not just about American marketing but more specifically what this thriller is actually about, and to a rather extensive degree. People complain about the flat, dry language. Someone somewhere must have compared it with Ikea products by now. Sturdy, plain, unadorned, functional, to the point sometimes where it almost becomes laughable. But it serves well as counterpoint to the lurid tenor of events here, guiding it easily into familiar rhythms of detective and especially police procedural fiction. The most dramatic and momentous incidents—sexualized cruelty continually overtopping itself—are invariably followed by scenes with liver pate and cucumber sandwiches, painstakingly assembled. The first Swedish movie version, made for television and chopped down later for theatrical release (I haven't yet caught up with the longer version or the other two installments, or with director David Fincher's more recent version), is a reasonably faithful adaptation, necessarily heightening some parts and compressing others for dramatic effect, which is what movies do. I like better the way the novel so flatly relates everything, the exposition as well as the dramatic climaxes, and in its just under 600 pages it seems to me to be remarkably structured—if this continues across all three similarly sized books, it's pretty impressive in its own right. Larrson was a journalist who died in 2004 at the age of 50 shortly after writing the trilogy. Mikael Blomkvist, our hero, is also a journalist, and Lisbeth Salander is the girl of the American title who comes to his aid. She lacks little that any other superhero in the movies these days has except for a colorful costume. Her superhuman qualities are much easier to take in the book somehow, maybe because people are otherwise so busy with shopping and preparing food. I suppose I could object to the casual and bountiful sex going on, but why bother? Everybody does a variation on that these days in places like the broader mystery genre. (I am a little more annoyed of the tired old idea that anal rape is the single greatest human horror imaginable. Wouldn't it be just as cruel and humiliating to once in awhile break every bone in someone's hand with a hammer? It would have the added advantage of imposing a permanent disability.) Also typically enough, our heroes and villains tend to be too easy to identify as good and bad, wearing their figurative white and black hats; moral complexity is a matter of punkish attitude, '60s-era tolerance and good will, tattoos, piercings, and sexual variety, which is to say, not much at all in evidence. On some level I wouldn't have it any other way. It reads well for bright light and warm weather next to bodies of water. Also fireplaces in winter.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, August 11, 2012

At Fillmore East (1971)

As self-indulgent double live albums from the '70s go, this one looms particularly large for me. First, I just loved it, specifically the guitar play and interplay across the solos, and all the places they take the long ones. I hadn't been to many concerts then and I was hungry for the experience, so as always I enjoyed that aspect of the live set too, projecting myself in and imagining making it to all these great shows. Then, in short order, I was sad that Duane Allman died. In high school the album became a major touchstone as one bunch put together a band and set about aping these numbers almost note for note, including even the elaborate peregrinations of "You Don't Love Me." They were good too. I loved that band—Seth—and it had a lot of followers at school too. For the first year or two this album was out I listened to it obsessively most days. Even then, although I did not like to admit it right out loud, I knew the best thing here by country miles is "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed," and I also noticed what a hard time they seemed to have ending songs—even the shorter ones (under six minutes) you can positively go take a bath in the time it takes them to get to the finish. All these years later, listening again, I can really hear the flaws, a lot of shaggy Southern-fried rock. But it can still sound pretty great too when they are choogling and feeling their way through the bluesy Georgia material. Duane Allman was a great player, with a raw and warm tone and a fluid way of getting it around, and Dickey Betts was a good match for him, counterpointing Allman's muscle with a more delicate style shadowing him. This is one of their finest hours. It's really great stuff in its best moments. I don't connect as much anymore with "You Don't Love Me," which unfortunately sounds busy and almost rinky-dink to me now, or even with "Whipping Post," my long-ago favorite. But sure enough, I swear no one wants to miss "Elizabeth Reed"—13 minutes of sheer poise and power delicately controlled, themes stated, elaborated, developed, and burst open, and then it ends on a dime. I don't know who's more surprised—you, me, the band, or the crowd that seems almost to forget to applaud for it, so startling is the emphatic finish.

Friday, August 10, 2012

Spirited Away (2001)

Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi, Japan, 125 minutes

Director/writer: Hayao Miyazaki

Production design: Norobu Yoshida

Art direction: Yoji Takeshige

Music: Joe Hisaishi

Cast/voices of (English language version): Daveigh Chase, Suzanne Pleshette, Jason Marsden, Susan Egan, David Ogden Stiers, Lauren Holly, Phil Proctor

In our 21st-century world of revitalized animated features, impresario Hayao Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli have arguably risen to the top of the heap (with Pixar leaving tooth scars on their heels), and Spirited Away has apparently earned the consensus distinction as being the best of the best of all its (and/or Miyazaki's) many impressive pictures. Spirited Away is indeed a fine adventure yarn, with a winning heroine, inventiveness by the pound, and a moment of overwhelming poignancy when the true nature of one of its most important characters is revealed—a truly inspired, even cunning revelation, which is fully appreciated only by paying the picture another visit in order to better grasp the nuances and intricacies in light of it.

At which point, for me, a funny thing happened. I was left more underwhelmed than I had been prepared for. It felt hollow and a little too long on subsequent viewings. Objectively, the movie is everything it was before—looks good, moves well, surprises often, with a spunky heroine you can't help rooting for up against unsettling, tough, and mysterious foes. It's just weird enough that I like it—but just conventional enough that I didn't love it. That helped me remember my main ongoing problem with the fantasy genre (where I don't even like Lewis Carroll, the most obvious source for this): it tends to require too much memorizing. And, in turn, that reminded me of my problems with so-called YA (young adult) literature, which has enjoyed a huge vogue in the past 20 years.

Director/writer: Hayao Miyazaki

Production design: Norobu Yoshida

Art direction: Yoji Takeshige

Music: Joe Hisaishi

Cast/voices of (English language version): Daveigh Chase, Suzanne Pleshette, Jason Marsden, Susan Egan, David Ogden Stiers, Lauren Holly, Phil Proctor

In our 21st-century world of revitalized animated features, impresario Hayao Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli have arguably risen to the top of the heap (with Pixar leaving tooth scars on their heels), and Spirited Away has apparently earned the consensus distinction as being the best of the best of all its (and/or Miyazaki's) many impressive pictures. Spirited Away is indeed a fine adventure yarn, with a winning heroine, inventiveness by the pound, and a moment of overwhelming poignancy when the true nature of one of its most important characters is revealed—a truly inspired, even cunning revelation, which is fully appreciated only by paying the picture another visit in order to better grasp the nuances and intricacies in light of it.

At which point, for me, a funny thing happened. I was left more underwhelmed than I had been prepared for. It felt hollow and a little too long on subsequent viewings. Objectively, the movie is everything it was before—looks good, moves well, surprises often, with a spunky heroine you can't help rooting for up against unsettling, tough, and mysterious foes. It's just weird enough that I like it—but just conventional enough that I didn't love it. That helped me remember my main ongoing problem with the fantasy genre (where I don't even like Lewis Carroll, the most obvious source for this): it tends to require too much memorizing. And, in turn, that reminded me of my problems with so-called YA (young adult) literature, which has enjoyed a huge vogue in the past 20 years.

Wednesday, August 08, 2012

Beatles, "I Should Have Known Better" (1964)

(listen)

It says on Wikipedia this is a result of the Beatles meeting Bob Dylan in 1964 ... something something about writing more meaningful lyrics. That's news to me in terms of the song, which I have known since I acquired the US version of the soundtrack product in approximately 1966 from a record club based out of Terre Haute, Indiana. It has always sounded like any other Beatles pop song of the time to me—confectionary, sweet, gorgeous, one of a kind, eminently singable, rockin' in place, and the kind of thing you want to hear again right away. So fucking good, to resort to the vernacular. Originally the B-side of "A Hard Day's Night," this is high Beatlemania we're talking about here, of course, 1964 bleeding into 1965, whose many terrific songs seem to vie for attention a lot, and often surprise. I keep forgetting how great they are until they are in my face again. (And, in honesty, I know there are a few I can do without, starting with "Can't Buy Me Love.") So I am probably writing about this now because at one point, fairly recently, shuffle brought it to my attention. But it's a good one, no worries on that score, friends. It has a valiant widescreen harmonica leading the attack, which lends it a railroad car texture that is likely its most distinguishing feature. It is otherwise the joyful high-spirited yelping, with harmonies, ladies and gentlemen (in stentorian Ed Sullivan tones always, of course), the Beatles. It's OK and explicitly recommended that you listen to it a few times at a go, not asking much at 2:44 or so.

It says on Wikipedia this is a result of the Beatles meeting Bob Dylan in 1964 ... something something about writing more meaningful lyrics. That's news to me in terms of the song, which I have known since I acquired the US version of the soundtrack product in approximately 1966 from a record club based out of Terre Haute, Indiana. It has always sounded like any other Beatles pop song of the time to me—confectionary, sweet, gorgeous, one of a kind, eminently singable, rockin' in place, and the kind of thing you want to hear again right away. So fucking good, to resort to the vernacular. Originally the B-side of "A Hard Day's Night," this is high Beatlemania we're talking about here, of course, 1964 bleeding into 1965, whose many terrific songs seem to vie for attention a lot, and often surprise. I keep forgetting how great they are until they are in my face again. (And, in honesty, I know there are a few I can do without, starting with "Can't Buy Me Love.") So I am probably writing about this now because at one point, fairly recently, shuffle brought it to my attention. But it's a good one, no worries on that score, friends. It has a valiant widescreen harmonica leading the attack, which lends it a railroad car texture that is likely its most distinguishing feature. It is otherwise the joyful high-spirited yelping, with harmonies, ladies and gentlemen (in stentorian Ed Sullivan tones always, of course), the Beatles. It's OK and explicitly recommended that you listen to it a few times at a go, not asking much at 2:44 or so.

Tuesday, August 07, 2012

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

#23: The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming/George Cukor/Mervyn LeRoy/King Vidor, 1939)

There are things I trace back directly to my early exposure to those annual television airings of The Wizard of Oz hosted by Danny Kaye, which usually occurred around Easter time, if I recall correctly: A fascination with tornado footage (better than ever nowadays via the storm-chaser shows). An appreciation for long roads that stretch to the horizon—my idle meeting-time doodles are full of them. How many shots of long roads and horizons, only partially blocked by the backs of our heroes, are in this? You'd be surprised.

More than anything, this is where my taste for horror movies started, because that's what basically happens here. It's a bit like that joke about going to the fights and a hockey game breaks out. Right in the middle of a colorful, goofy MGM musical, there's a witch who scares the hell out of any sensible 9-year-old expecting carefree, happy-go-lucky, parent-approved saccharine. Or anyway that's what happened to me. Mary Poppins this is not. Getting through it was a rite of endurance for a lot of years, a battle with my own adrenaline, and I didn't always win. But I survived, and that's the paradoxical pleasure of horror reduced to its fine point.

There are things I trace back directly to my early exposure to those annual television airings of The Wizard of Oz hosted by Danny Kaye, which usually occurred around Easter time, if I recall correctly: A fascination with tornado footage (better than ever nowadays via the storm-chaser shows). An appreciation for long roads that stretch to the horizon—my idle meeting-time doodles are full of them. How many shots of long roads and horizons, only partially blocked by the backs of our heroes, are in this? You'd be surprised.

More than anything, this is where my taste for horror movies started, because that's what basically happens here. It's a bit like that joke about going to the fights and a hockey game breaks out. Right in the middle of a colorful, goofy MGM musical, there's a witch who scares the hell out of any sensible 9-year-old expecting carefree, happy-go-lucky, parent-approved saccharine. Or anyway that's what happened to me. Mary Poppins this is not. Getting through it was a rite of endurance for a lot of years, a battle with my own adrenaline, and I didn't always win. But I survived, and that's the paradoxical pleasure of horror reduced to its fine point.

Sunday, August 05, 2012

Don't Cry (2009)

I spent a good deal of time believing Mary Gaitskill was a better story writer than novelist, chiefly because there were two books of (very good) stories to one flawed novel that I loved in spite of its flaws—even because of some of its flaws. Veronica changed that calculation, though I'm not entirely sure it isn't flawed too in its ways. But it's such an impressive leap of imagination and memory that it's at least the equal of either collection, let alone any one story. Now Don't Cry seems to take that tilt another step in. Gaitskill is growing older and more ponderous like the rest of us—that's a big part of what made Veronica great—but it also means her crystalline prose can become tangled as it attempts to pin down endless nuance. The arduous quantum mechanics of precision writing will have its toll, and many patches in these stories feel a good bit fussed over. It's reminiscent of the arc of Henry James's progression, perhaps, which I suppose means I should give them another chance. Some I found a chore to plow through—"Folk Song," "Mirror Ball," "The Arms and Legs of the Lake." Others, such as "Today I'm Yours" and "The Little Boy," work reasonably well. "College Town, 1980" was more disappointing because it started so well. "The Agonized Face" is possessed of interesting ideas, and thus a bit arid and intellectualized. I like the last two stories best, I think, "Description" and "Don't Cry." They are linked, but in an odd way, unfolding as two very different—and very differently approached and told—episodes from the life of a creative writing instructor. In the first she has a fairly minor, offstage role. In the second she is present as a supporting player, albeit a key one, and one whose own biography intrudes on and affects, sometimes directly, the development of events. Gaitskill works best for me when she is dealing with the negative space between human cruelty, emotional distance, and the longing for connection. Almost entirely gone here are the references to sadomasochism—as lifestyle, as orientation, as underpinning philosophy—and I find that I miss them. Maybe this represents a kind of maturity for her, but I still miss them.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, August 04, 2012

Loaded (1970)

I knew this was a great album when I finally flipped it over, and yeah, I know I am dating myself with that. The first side is front-loaded with an impressive array of post-John Cale highlights, "Sweet Jane," "Rock and Roll," and "New Age," by name. If you don't know them you should, probably in about that order, not to great preachy or judgmental. They are alone worth price of admission, for sure. But what's on the back has more sides of Lou Reed the tender, fresh and surprising every time they show (he always did appear to know how good that side of his shtick is as two other such, "Who Loves the Sun" here and "Sunday Morning" from the banana album, were designated to open two of rawk's stone great albums). For a time I think I might even have been at least as infatuated with the back of this album as with its front (and that is and remains "Oh! Sweet Nuthin'" notwithstanding, though I admit it grows on me). "Head Held High" is about the usual squall (bearing in mind that generally speaking everything here is at least slightly above average), but "Lonesome Cowboy Bill," "I Found a Reason," and "Train Round the Bend" seem to me unique little chapters in all of Lou Reed's catalog, and utterly worthy. "Lonesome Cowboy Bill" makes like a kiddy song, with the sing-along invitation of the melody and then cowboys too, as advertised. Riding horses and everything, in rodeos, no less. It's a goof from nowhere and plain charming. "I Found a Reason," by contrast, is serious about its romance and other things eternal, built on more kiddy-style vocal harmonies and tunes. It gives itself away all heartfelt and adolescent on the speech from Lou: "Honey, I found a reason to keep living. And you know the reason, dear, it's you." How Lou Reed was getting away with such adolescent maunderings as a 27-year-old is another question, but lay that to the side. He was, and would for awhile longer. And it doesn't matter: once he's done talking the singing on "I Found a Reason" really starts, and if you know what's good for you you're singing right along. At the top of your lungs if you can manage it. It is really quite a remarkable moment, and it sneaks up on you too. Then "Train Coming Round the Bend" starts grinding its insinuating way in, with the kind of groove that either Creedence Clearwater Revival or T. Rex could drift into as well. And out on the 7:24 of cooing and sighing that is "Oh! Sweet Nuthin'" (great title, that one) to polish off the lovely suite and a great side too. That is one of the benefits of liking the first side so much. It leads to additional exposure to the second side and other good things.

Friday, August 03, 2012

The Last Days of Disco (1998)

USA, 113 minutes

Director/writer: Whit Stillman

Photography: John Thomas

Music: Mark Suozzo

Editors: Andrew Hafitz, Jay Pires

Cast: Chloe Sevigny, Kate Beckinsale, Chris Eigeman, Matt Keeslar, Mackenzie Astin, Matthew Ross, Tara Subkoff, Burr Steers, David Thornton, Jaid Barrymore, Michael Weatherly, Robert Sean Leonard, Jennifer Beals

There are thing to complain about in The Last Days of Disco—it's hardly flawless. But I was compelled to revisit it after seeing screenwriter and director Whit Stillman's first movie since, 14 years on, Damsels in Distress, which came out earlier this year. Not only did I adore Damsels in Distress, but I also find that I like The Last Days of Disco a whole lot more in its glow. As a matter of fact, in many ways Damsels practically picks up where Last Days left off, certainly in terms of the never-ending search to find truth and meaning in popular dance crazes and the social upheavals attending them. Everything anyone might rightly find fault with does not prevent The Last Days of Disco from being perfectly insinuating and a complete winner start to finish, a broad farce playing our nominal superiors, namely New York City's Upper East Side ruling class, for witless buffoons.

I think I didn't comprehend before how funny Stillman is at sending up these people—or, more specifically, their children. Making privileged WASPs into vicious, plainly dumb caricatures may look easy but making it work is probably his best trick in a whole magic bag full of them, because he's kind of gentle about it and yet he shows no mercy. To a person, no one here is likeable (or, in fairness, entirely unlikeable either). There's a lot of skill to the way Stillman renders them as well-educated, well-mannered, well-spoken, well-dressed, and well-bred preening nincompoops, alternately strutting about like barnyard cocks or cringing to perceived authority. It may be class warfare, but it's deliriously pleasurable.

Director/writer: Whit Stillman

Photography: John Thomas

Music: Mark Suozzo

Editors: Andrew Hafitz, Jay Pires

Cast: Chloe Sevigny, Kate Beckinsale, Chris Eigeman, Matt Keeslar, Mackenzie Astin, Matthew Ross, Tara Subkoff, Burr Steers, David Thornton, Jaid Barrymore, Michael Weatherly, Robert Sean Leonard, Jennifer Beals

There are thing to complain about in The Last Days of Disco—it's hardly flawless. But I was compelled to revisit it after seeing screenwriter and director Whit Stillman's first movie since, 14 years on, Damsels in Distress, which came out earlier this year. Not only did I adore Damsels in Distress, but I also find that I like The Last Days of Disco a whole lot more in its glow. As a matter of fact, in many ways Damsels practically picks up where Last Days left off, certainly in terms of the never-ending search to find truth and meaning in popular dance crazes and the social upheavals attending them. Everything anyone might rightly find fault with does not prevent The Last Days of Disco from being perfectly insinuating and a complete winner start to finish, a broad farce playing our nominal superiors, namely New York City's Upper East Side ruling class, for witless buffoons.

I think I didn't comprehend before how funny Stillman is at sending up these people—or, more specifically, their children. Making privileged WASPs into vicious, plainly dumb caricatures may look easy but making it work is probably his best trick in a whole magic bag full of them, because he's kind of gentle about it and yet he shows no mercy. To a person, no one here is likeable (or, in fairness, entirely unlikeable either). There's a lot of skill to the way Stillman renders them as well-educated, well-mannered, well-spoken, well-dressed, and well-bred preening nincompoops, alternately strutting about like barnyard cocks or cringing to perceived authority. It may be class warfare, but it's deliriously pleasurable.

Wednesday, August 01, 2012

Wire, "I Should Have Known Better" (1979)

(listen)

This comes from Wire's third album, 154, my favorite album by one of my favorite New Wave bands—or, "post-punk," I guess maybe is the term of art they prefer. But note date and see cover. Latter days, with all the writing about songs, I sometimes lose track of how fabulously dedicated I have been, and can be still, to the art and science of the Rock Album ... man. So that's where I'm coming from when I say, really, you need to hear all of 154, the whole thing, every bit of it. Anyway, you can hear the first thing with this, as it is the intense big kickoff side 1 album opener tune. It starts on its furry, throbbing beat and quickly opens up into more throbbing, on suddenly infinitely opening levels, until finally the frog-throated B.C. Gilbert enters with the sing-songy chant. Then you're about in, not even 30 seconds, and the whole song keeps going on that way, an aural equivalent of a fast ride in an up elevator, ultimately capable, in one very nice moment, of sustaining an electric guitar chord. It never adds up that much about the regret implied in the title ("I've redefined the meaning of vendetta"?), but that's never been an issue. I am more interested in the way it makes one more bridge between a Martin Hannett kind of thing going on then in Manchester, whereas Wire operated out of London (and had 154 gigs to their credit at the time they recorded this), and the kind of mad swirling trip hop that came much later, which I guess has its own debts as well to the Manchester thing. Refracted in certain ways, this—the whole album, I'm saying—could be a distant cousin of that, wholly original in its own right, and really getting down to their business and doing it right about here.

This comes from Wire's third album, 154, my favorite album by one of my favorite New Wave bands—or, "post-punk," I guess maybe is the term of art they prefer. But note date and see cover. Latter days, with all the writing about songs, I sometimes lose track of how fabulously dedicated I have been, and can be still, to the art and science of the Rock Album ... man. So that's where I'm coming from when I say, really, you need to hear all of 154, the whole thing, every bit of it. Anyway, you can hear the first thing with this, as it is the intense big kickoff side 1 album opener tune. It starts on its furry, throbbing beat and quickly opens up into more throbbing, on suddenly infinitely opening levels, until finally the frog-throated B.C. Gilbert enters with the sing-songy chant. Then you're about in, not even 30 seconds, and the whole song keeps going on that way, an aural equivalent of a fast ride in an up elevator, ultimately capable, in one very nice moment, of sustaining an electric guitar chord. It never adds up that much about the regret implied in the title ("I've redefined the meaning of vendetta"?), but that's never been an issue. I am more interested in the way it makes one more bridge between a Martin Hannett kind of thing going on then in Manchester, whereas Wire operated out of London (and had 154 gigs to their credit at the time they recorded this), and the kind of mad swirling trip hop that came much later, which I guess has its own debts as well to the Manchester thing. Refracted in certain ways, this—the whole album, I'm saying—could be a distant cousin of that, wholly original in its own right, and really getting down to their business and doing it right about here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)