It turns out that Harlan Ellison's longish story is not just riffing on poor Robert Bloch's previous story, "A Toy for Juliette," but is self-consciously the next chapter. I say "poor" Robert Bloch because he has also been roped into writing the introduction to this story and really doesn't have a lot to say. Of course it sounds like Bloch has high regard for Ellison (he would have to, either way) and I get the sense it's sincere, though he appears somewhat bewildered by the requests. In many ways, Bloch and Ellison are opposites. Both are fascinated by cruelty, but Bloch is more circumspect, laying little traps in his writing that are designed to bloom cunningly into clarity. Whereas Ellison is verbose and explicit. Bloch is a folk song murder ballad. Ellison is an opera. Ellison's story is three times the size of Bloch's, and doesn't come with much of a surprise the way Bloch's does—indeed, was engineered to. I think of Ellison as sort of the Lester Bangs of science fiction, which means in part that I'm OK with his excesses. What interests me most about these two stories is the suggestion of an old guard / new blood distinction. Bloch started publishing in the 1930s. Also, for what it's worth, he's probably known more as a horror or maybe crime fiction writer. In his afterword, Ellison discusses how hard his story was to write. It took more than a year in fits and starts. And it feels a little labored, not to say overdone. It might be the story he was hoping for from Bloch, with the Victorian savagery of the killer juxtaposed by the gleaming technology of The Future. It's going to be heavy for the future when it tangles with Jack the Ripper, man. And so it is, at some length. Bloch's story might be better—if it's more gimmicky, it's also more crafted, and unpleasant, which has to be part of the point. Ellison's is more like a report from his brain which has stalled with vapor lock on the creative problem. It can be highly effective, and in general is one of the most tightly written stories here, but it never has much of anywhere to go. Ultimately it's Jack the Ripper who does most of the work in all of these stories, including Bloch's original from the 1940s, "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper." In other words, they tend to be ever more grotesque exercises in "when the legend becomes fact, print the legend."

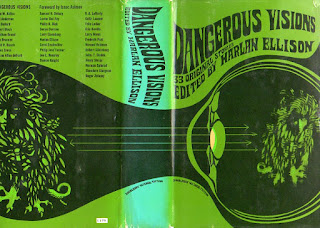

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Law & Order, s4 (1993-1994)

The fourth season of Law & Order—getting it across the finish line for rerun syndication, otherwise known as The Rest of Our Lives—was an active one in terms of the original strategy of focusing on specific justice system roles, occupied by shifting characters, rather than the other way round which most of TV did, at least as of the mid-'90s (Bob Newhart, Tom Selleck, William Shatner, etc.). So without preamble or explanation a white man and a black man (Dann Florek as chief of detectives Donald Cragen and Richard Brooks as second-chair ADA Paul Robinette, respectively) are replaced even before the start of the new season by a black woman and a white woman (S. Epatha Merkerson as chief of detectives Anita Van Buren and Jill Hennessy as second-chair ADA Claire Kincaid, respectively). Merkerson, of course, would turn out to be the most prolific player in the show, appearing in 391 episodes (counting one role in an episode from an earlier season as someone other than Van Buren—#3 Jerry Orbach has an earlier one-off like that too). There did not appear to be any hard feelings—Florek directed a few episodes in this season, and much later reappeared, again as Cragen, in 331 episodes of the spinoff Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (which this year will match the 20-season run of the flagship, and can pull ahead with one more renewal next spring). Mastermind Dick Wolf and crew get right to the backstory of Claire Kincaid and the clashes Van Buren faces with men who report to her. In terms of the staples of episode-based TV—stories, characters, production, and performances—Law & Order arrived practically hitting on all cylinders and the fourth season is no exception. One of the highlights is an epic confrontation, verging on super-heroic, between ADA Ben Stone (Michael Moriarty) and a rascally brilliant opponent in ex-con Phillip Swann (Zeljko Ivanek). Plus there are the usual intriguing if random markers of prescience, such as the Russian mafia operating in the background, or another oblique appearance by Donald Trump (I'm starting to understand the deep roots he holds in popular culture, even if he was never anything to me).

The biggest change of this season doesn't happen actually until the next—that is, the replacement of ADA Stone with Jack McCoy (Sam Waterston), who would go on to become #2 behind Merkerson for ubiquity in the show, appearing in 368 episodes. His domination / overstaying is an issue for later seasons, but because he essentially became the ADA associated with the show, inevitably it overshadowed Moriarty's work, which was every bit as good. In retrospect now it looks a little like some kind of mistake that was corrected, so I want to say something for Moriarty on his way out. I understand things look different on the inside of TV in terms of ratings considerations—what looks to us like "calling this rut a groove and going with it" too often misunderstands the rewarding commercial facts of a rut. It might well have hurt the show's popularity and even cut the run down earlier if they had swapped out Waterston for a third ADA sooner (and then exited him altogether from the show, please). I always wondered what Treat Williams would do with the role, for example. Moriarty and Waterston were both gifted theatrical actors leaning toward Method styles in approach. For players like that, a thundering righteous prosecutor is a dream horse of a role. Moriarty played his with a courtly grace and severity that felt like Ben Stone might have his origins in the South. Stone moved swiftly to use the justice system tools at his disposal, and when he was convinced he was right he sometimes strayed into gray areas of ethics and even law. Sometimes he just plain made mistakes. But he had compassion too and Law & Order screenplays often make ADAs more arbiters of justice, possessed of higher wisdom—or so they would like to think—than simply functioning bureaucrats (which may or may not be the reality, I wouldn't know). In many ways, Moriarty framed out the ADA role that would dominate the show and Waterston always worked within it. If anyone had known it would go 20 years, I wish they would have given Moriarty another one, brought in Waterston for only five, and then two others back of that (neither of them Linus Roache, please). But now I'm living in a dream world.

The biggest change of this season doesn't happen actually until the next—that is, the replacement of ADA Stone with Jack McCoy (Sam Waterston), who would go on to become #2 behind Merkerson for ubiquity in the show, appearing in 368 episodes. His domination / overstaying is an issue for later seasons, but because he essentially became the ADA associated with the show, inevitably it overshadowed Moriarty's work, which was every bit as good. In retrospect now it looks a little like some kind of mistake that was corrected, so I want to say something for Moriarty on his way out. I understand things look different on the inside of TV in terms of ratings considerations—what looks to us like "calling this rut a groove and going with it" too often misunderstands the rewarding commercial facts of a rut. It might well have hurt the show's popularity and even cut the run down earlier if they had swapped out Waterston for a third ADA sooner (and then exited him altogether from the show, please). I always wondered what Treat Williams would do with the role, for example. Moriarty and Waterston were both gifted theatrical actors leaning toward Method styles in approach. For players like that, a thundering righteous prosecutor is a dream horse of a role. Moriarty played his with a courtly grace and severity that felt like Ben Stone might have his origins in the South. Stone moved swiftly to use the justice system tools at his disposal, and when he was convinced he was right he sometimes strayed into gray areas of ethics and even law. Sometimes he just plain made mistakes. But he had compassion too and Law & Order screenplays often make ADAs more arbiters of justice, possessed of higher wisdom—or so they would like to think—than simply functioning bureaucrats (which may or may not be the reality, I wouldn't know). In many ways, Moriarty framed out the ADA role that would dominate the show and Waterston always worked within it. If anyone had known it would go 20 years, I wish they would have given Moriarty another one, brought in Waterston for only five, and then two others back of that (neither of them Linus Roache, please). But now I'm living in a dream world.

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (1860)

One of the best book titles ever, first. As a slave narrative, it's in the mode of the adventure story, an escape tale almost exclusively. It's almost fun because the plan of William and Ellen Craft is so clever and yet full of deadly risk. It offers the usual view of human beings as property that was so common then and seems so grotesque now. The pervasive acceptance of that in these narratives remains one of their most disturbing elements. But there's less of that here. The plan is that Ellen will pose as a man and William's master, as the two of them travel together. Ellen is a "quadroon" (their word) and can pass for white. She cannot read or write, neither of them can, so they make her appear to have an injured right hand, and she asks others to sign and fill things out for her. Everybody uses the N-word and abolitionists are reviled. Ellen is privy to some unguarded conversations about the slavery question, which was then becoming more and more central in American life. The close calls here are suspenseful, often involving the necessity to show papers for William, which of course they don't have. At one point someone is suspicious because Ellen won't sign something. At another point someone gives her a business card and she makes a decision not to look at it because she might give herself away if it is upside down and she doesn't turn it right. William is the author and he occasionally indulges an impulse to be smug about the people they fool. But I'll give him that—what they did was brave. Going with the idea that many of these slave narratives were shaped toward simple points, the emphasis here is on their intelligence and resourcefulness. They could plan the initial getaway with lots of time to gather information and think it through. But once they were traveling north—a thousand miles is reasonably literal—they had to make their story work with whatever they encountered. And they did. It's a remarkable story. Sad then that they finally realized they still weren't safe in the North, as fugitive slaves, perhaps not even in Canada, and eventually settled in London.

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

Saturday, August 18, 2018

SremmLife 2 (2016)

Whenever I'm drawn to an album in the first place by hit singles—in this case, "Swang" and especially "Black Beatles"—I can't be surprised if the whole thing doesn't necessarily add up to more than the sum of its parts. And SremmLife 2 does not, though most of these tunes have hooks and other redeeming qualities and at least one of the other singles and a few others distinguish themselves enough to make it worth throwing them into shuffle mixes. The duo of Slim Jxmmi and Swae Lee took the strange name Rae Sremmurd from the name of a former label, EarDrummers, spelled backward, sort of. They're from Tupelo, Mississippi. Co-producer and EarDrummers principal Mike Will is based out of Atlanta. They made the first single from SremmLife 2 "By Chance," which is a fairly aimless if insinuating exercise riffing off a piano figure reminiscent of one by the Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti from the movie Eyes Wide Shut. "By Chance" never charted but I enjoyed the excuse to roam around the movie soundtrack another time. The big hit for Rae Sremmurd came with the third try from this album. "Black Beatles" turned out to be the monster, spending weeks in and out of the #1 spot. You probably know it for that reason, and know already what a blast of fresh free-floating energy it is (although I understand you might be tired of it now), with a rhythm pitched face-forward and moving like the lumbering Frankenstein monster around the edges of all the hairpin switch-ups. It's a dicey move to name check Liverpool's finest but when your pop instincts are this good no one can object. Some other songs I've learned to look forward to here include the sinuous "Do Yoga," describing a lifestyle of champions ("all my girls do yoga, then get high at night"), "Set the Roof," as in set it on fire, a rousing rave-up, and "Take It or Leave It," another sweet example of how far and easily they can slip over into pop confectioneries. "Swang" was a solid follow-up to "Black Beatles." I haven't caught up with their latest yet, but SremmLife 2 is already a big advance over the debut.

Friday, August 17, 2018

Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948)

USA, 87 minutes

Director: Max Ophüls

Writers: Howard Koch, Stefan Zweig, Max Ophüls

Photography: Franz Planer

Music: Daniele Amfitheatrof

Editor: Ted J. Kent

Cast: Joan Fontaine, Louis Jourdan, Mady Christians, Art Smith, Marcel Journet, Howard Freeman

This is one of those movies I seem to have a hard time making up my mind about. Sometimes I wonder how I end up seeing these movies I'm ambivalent about so often. Director and cowriter Max Ophüls was a primary interest of movie critic Andrew Sarris, which is where I first heard and became curious about Ophüls's work. Another highly regarded picture by him, at least as measured by the critical lists collated for the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?, is Madame de... (this includes Sarris, who considered it the greatest movie ever made). At the moment, to give you some idea, Madame de... is at #120 on that list and Letter From an Unknown Woman at #122 (Ophüls's next-highest is Lola Montes at #323, another movie I'm ambivalent about but never mind). I've always had regard for Madame de..., along with some others by Ophüls I like quite a bit such as The Reckless Moment and Caught (also known as Wild Calendar). But Letter From an Unknown Woman has often posed challenges for me even in staying awake.

It's not Joan Fontaine and never was, but I'll get to that in a minute. In an attempt to make all this even less interesting if that's possible, I want to speculate that my ambivalence might be related to media format. That is, the copy of Letter From an Unknown Woman I've had for many years now is a VHS cassette, which is serviceable enough in 2018 but increasingly impractical, most notably because there is no longer a way to operate the machine with a remote. And I'm spoiled now—without a remote it's almost too hard to watch a picture carefully. So I fretted about it and finally decided to pay the $2 to watch it on Amazon Prime, and what do you know, the whole darn thing came to life again in a big new way. I can't explain this very well, but I know I liked Letter From an Unknown Woman the first time I saw it, in a theater setting.

Director: Max Ophüls

Writers: Howard Koch, Stefan Zweig, Max Ophüls

Photography: Franz Planer

Music: Daniele Amfitheatrof

Editor: Ted J. Kent

Cast: Joan Fontaine, Louis Jourdan, Mady Christians, Art Smith, Marcel Journet, Howard Freeman

This is one of those movies I seem to have a hard time making up my mind about. Sometimes I wonder how I end up seeing these movies I'm ambivalent about so often. Director and cowriter Max Ophüls was a primary interest of movie critic Andrew Sarris, which is where I first heard and became curious about Ophüls's work. Another highly regarded picture by him, at least as measured by the critical lists collated for the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?, is Madame de... (this includes Sarris, who considered it the greatest movie ever made). At the moment, to give you some idea, Madame de... is at #120 on that list and Letter From an Unknown Woman at #122 (Ophüls's next-highest is Lola Montes at #323, another movie I'm ambivalent about but never mind). I've always had regard for Madame de..., along with some others by Ophüls I like quite a bit such as The Reckless Moment and Caught (also known as Wild Calendar). But Letter From an Unknown Woman has often posed challenges for me even in staying awake.

It's not Joan Fontaine and never was, but I'll get to that in a minute. In an attempt to make all this even less interesting if that's possible, I want to speculate that my ambivalence might be related to media format. That is, the copy of Letter From an Unknown Woman I've had for many years now is a VHS cassette, which is serviceable enough in 2018 but increasingly impractical, most notably because there is no longer a way to operate the machine with a remote. And I'm spoiled now—without a remote it's almost too hard to watch a picture carefully. So I fretted about it and finally decided to pay the $2 to watch it on Amazon Prime, and what do you know, the whole darn thing came to life again in a big new way. I can't explain this very well, but I know I liked Letter From an Unknown Woman the first time I saw it, in a theater setting.

Thursday, August 16, 2018

"A Toy for Juliette" (1967)

Robert Bloch's turn at the Dangerous Visions open mic comes with a long backstory and a surprise sequel. Bloch, who is probably best known today for writing the novel on which Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho is based. was an early acolyte and correspondent of H.P. Lovecraft. In 1943, Bloch published one of his most famous stories, "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper," which imagines the legendary London serial killer as an immortal being who must kill women periodically to live on. In many ways the story made Bloch's career. It was often anthologized and often imitated. With that in mind, almost 25 years later, editor Harlan Ellison asked Bloch to write a story for this collection about Jack the Ripper in the future. This story is the result. However, in his lengthy introduction to the story—which is actually longer than the story itself, and includes direct input from Bloch—Ellison admits it wasn't the story he had been thinking of. It is certainly solid in terms of psychotic cruelty, sadism, etc., which Bloch was good at. Practically clinical, in fact. Still, Ellison had his idea and asked Bloch's permission to do his own version of Jack the Ripper in the future, and also asks him to write the introduction for it (you can see that these story introductions and afterwords are a lively and integral part of the collection). That's the next story in this special two-part episode, which Ellison counsels us to read in tandem—the whole thing, both introductions, both stories, and both afterwords by the Ellison/Bloch tag team. More on that next. "A Toy for Juliette," meanwhile, is basically a chamber drama with a time travel sideshow involving sadists. Or psychopaths or sociopaths—always get those two mixed up. It's post-apocalyptic times in the future. Not many humans on the planet. Juliette and her grandfather are hunkered up in some stronghold, from which Grandfather time travels, collecting specimens from the past. Bloch goes a bit far in suggesting they include Amelia Earhart and other famous disappearing people. Once Juliette gets hold of them she tortures them to death. The story spends a considerable amount of time on her methods. Then Jack the Ripper shows up as a specimen—he's another famous disappearing person, of course (conceivably, Grandfather could get around to the Zodiac killer as well). "A Toy for Juliette" is a creepy and unpleasant story, and totally professional. We'll see what Ellison had in mind for the Jack the Ripper scenario next.

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Monday, August 13, 2018

Won't You Be My Neighbor? (2018)

Full disclosure and true confession: I was nearly 13 when the first Mister Rogers' Neighborhood aired in Pittsburgh in February 1968. Because the show was generally intended for children around ages 2 to 5, perhaps up to 8, even by the time I'd heard of it I had no interest in it. It was for babies. Down the line, when Sesame Street and Electric Company came along and grew popular I looked in at them all out of curiosity. By then I was maybe 21? Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was the one I liked least, and honestly, something about Rogers's immaculate imperturbability gave me the willies. He was hard to watch. I experienced some of that again in about the first quarter of this remarkable picture by veteran documentary producer / director Morgan Neville (Best of Enemies, 20 Feet From Stardom). Fred Rogers is so matter-of-fact about looking square into the camera and saying things like he wants to be your friend and he likes you just the way you are, that it makes me squirm, still. In fact, as the movie went along, I started to realize he actually has quite a bit in common with Jonathan Richman, the eccentric singer-songwriter who abandoned an amazing rock band 40 years ago to go his own way, writing songs like no one else writes about summer sadness, dancing in lesbian bars, and Vermeer. The affect presented to the world by both Rogers and Richman is so open, naïve, and sincere that it's hard not to wonder about things like mental illness. There's a great clip here from the old Tomorrow show with Tom Snyder where Snyder tries to pierce the facade and finds that's all there is. What you see is what you get with Fred Rogers. Clue: He's not the one we have to worry about being mentally ill. Our cynicism and other psychic poisons make us mean and suspicious, and the hardest thing to see and understand at all is just that. Rogers flew right at questions like "am I a mistake?" and issues like death, divorce, disability, loneliness, rejection. This movie is full of absolutely fearless moments from his TV show and it is uncanny what he produced. Two days after the assassination of Robert Kennedy, for example, Rogers went on the air with a segment where his Daniel puppet suddenly asks, "What does assassination mean?" It is a moment that only deepens into itself. Somehow it captures the shock and the grief of the time. The immediate response, even more than 50 years later, is palpable relief that a taboo subject has at last come into the open. There is a kind of catching the breath for what happens next (the cynic in me also wants to call attention to what great TV it is, even or especially in our reality TV era). I never knew Rogers was an ordained Presbyterian minister—a non-flaunting Christian, the best kind. And one thing that everyone seems to agree on about this fellow is that the more you know about him the more you respect and love him. All it took for me was the hour and a half of this amazing documentary.

Sunday, August 12, 2018

A Handful of Dust (1934)

I read some Evelyn Waugh when I was a teen (and much later saw the TV miniseries Brideshead Revisited) but not much sticks. He's British and very dry, his humor easy to miss until you step back to look at the bigger picture. Tony and Brenda Last are in a comfortable if not passionate marriage, but trouble is on the horizon early in this story. Tony is landed aristocracy. His estate, Hetton Abbey, has been in his family for generations and is practically more important to him than his marriage. But Brenda finds it a cold old barn and has little interest in Tony's endless renovation projects. Before long she has taken an apartment in London, and then a lover, John Beaver, a shallow society player who amuses her. The marriage falls apart in slow motion and there's even more bad luck ahead for Tony. Eventually it's divorce, but Brenda and Beaver are heartless in their demands, overplaying their hand. Once Tony realizes they would force him to sell Hetton to settle with them, he finally understands what he is up against, says Fuck you (figuratively—that's me talking not Waugh), and trots off with a friend on a jaunt to South America as "explorers." This does not go well, to say the least, and Tony's final fate is inspired, creepy—and comic, when you step back. Interestingly, Waugh also wrote an alternative ending, in which Tony escapes the jungle and returns to England and reunites with Brenda, who has been rejected by Beaver when it becomes evident she's not actually wealthy. It's not a happy ending either, but it's happier. I thought it was interesting, and enjoyed the chance to read it, but prefer Waugh's first choice too. Waugh's language is careful and nuanced, very good in many small ways—his colors, for example, can be almost distractingly precise and vivid. And he's sly too. The story slips back and forth between a comically acerbic voice and tender moving tragedy, like an optical illusion with two competing images. Is it profiles of two faces or is it a vase? Still, though it is often well done and some parts are great, I think overall it might be just a little too reserved and British for me.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, August 11, 2018

Skeleton Tree (2016)

Nick Cave has been a problem I've only worried infrequently and from a distance. I don't know the Birthday Party that well—everything I've ever heard has sounded generic to me within a narrow range of punk. Then his long Elvis / U.S. South phase with the Bad Seeds (from approximately The Firstborn Is Dead, and hitting a crashing crescendo with Murder Ballads) left me intrigued but usually unsatisfied. He seemed to have a head full of steam-powered notions, like Elvis as the slouching beast, but they never seemed to get traction. At least I found a new appreciation for the quiet in the original murder ballads—that's the power of them. Then, finally, as if learning the lesson himself, with The Boatman's Call Cave and band more latched on to something like a demented cross between lounge and hymnal music, with high-flown biblical language ("Into my arms, O Lord," "The ring is locked upon the finger," "It was the year I officially became the bride of Jesus," etc.) as he indulged spiritual yearnings in a suave, sinister, and somehow depraved context. It really works for me—maybe it's the widow's peak. At his best, Cave has an unaffected way of reaching back effortlessly to deepest cultural sources, like the Bible, for the most prized antiques. My favorite is No More Shall We Part, but others I've dipped into less intensely fit the bill too: The Boatman's Call, the double album Abbatoir Blues / The Lyre of Orpheus, and Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! I never caught up with the 2013 Push the Sky Away and decided I wanted to check in again with the latest, from two years ago, which came in the wake of the accidental death of Cave's son. It sounds much like more of the same to me, for better or worse. It's supercharged on one level with a somber air of grief and yet Cave as the singer is distanced and calculated. He often sounds like he is reading poetry, or mumbling to himself. He and the music drift into fields of ambience as if losing trains of thought, a neatly done mimic of a mind temporarily unmoored by passing circumstances. At these points his skill at scoring movies also shows (Wind River, Hell or High Water, The Road, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford). At other times, as in "I Need You" (an iconic title he's renting from the Beatles, America, and LeAnn Rimes), the warbling position of faith could not be more clear or tender. An angel named Else Torp sits in on "Distant Sky." As for the Bad Seeds, it seems to be the second nature of Cave and these players to be nearly perfectly in synch after all this time playing together, notably Warren Ellis, cowriter with Cave of all these songs. The result might be classified as a slightly more literary version of Neil Young's Tonight's the Night. Not his best but worth a visit.

Friday, August 10, 2018

A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

USA, 155 minutes

Director/writer: John Cassavetes

Photography: Mitch Breit, Al Ruban

Music: Bo Harwood

Editors: David Armstrong, Sheila Viseltear

Cast: Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk, Katherine Cassavetes, Lady Rowlands, Fred Draper, Matthew Cassel, Matthew Labyorteaux, Christina Grisanti, George Dunn, Mario Gallo, Eddie Shaw

There is a lot of interesting background to the making of this movie—director and writer John Cassavetes mortgaged his house and borrowed heavily to get it done and then an unusual distribution strategy had to be pursued when even independents declined to work with it. I recall a lot of discussion at the time it was released of strategies of improvisation in the performances. Much about the picture did seem shaggy and rough. But somehow that is no longer the case. It feels to me now like a consummately professional production, and points such as the handheld shooting only give it more immediacy. It is excellent filmmaking. It looks great, its story is tender and surprising by turns, and except for the rich color stock of the film, which looks like 100% American '70s cinema, it could have been released even in the last five years. The movie it reminds me of now is Boyhood, with its penetration into the ways a family orbits itself.

It's Cassavetes's film by all the normal markers, but still it owes everything to the performance of his wife Gena Rowlands as Mabel Longhetti. Mabel is married to Nick (Peter Falk) and they have three kids under 10. At first, in a reflexive sort of way, the movie might appear to be courting trouble by taking on the theme of insanity, which is so often the band-aid of fiction. But mental illness in A Woman Under the Influence is not a flimsy way to explain something. It's just the given, and as such the subject itself of the movie, focusing especially on the chaos it produces on the loved ones of the sufferer. In this case, Cassavetes seeks an interesting extra layer by casting his mother and Rowlands's mother as the mothers of Nick and Mabel, respectively. Medicine and attitudes have advanced since the '70s, but the portrait of the Longhetti family in crisis is still perfectly recognizable, with Nick attempting to come to terms with the reality of his wife's condition, fighting through denial and shame, even as Mabel continually loses her grip and blows every chance she gets in polite company.

Director/writer: John Cassavetes

Photography: Mitch Breit, Al Ruban

Music: Bo Harwood

Editors: David Armstrong, Sheila Viseltear

Cast: Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk, Katherine Cassavetes, Lady Rowlands, Fred Draper, Matthew Cassel, Matthew Labyorteaux, Christina Grisanti, George Dunn, Mario Gallo, Eddie Shaw

There is a lot of interesting background to the making of this movie—director and writer John Cassavetes mortgaged his house and borrowed heavily to get it done and then an unusual distribution strategy had to be pursued when even independents declined to work with it. I recall a lot of discussion at the time it was released of strategies of improvisation in the performances. Much about the picture did seem shaggy and rough. But somehow that is no longer the case. It feels to me now like a consummately professional production, and points such as the handheld shooting only give it more immediacy. It is excellent filmmaking. It looks great, its story is tender and surprising by turns, and except for the rich color stock of the film, which looks like 100% American '70s cinema, it could have been released even in the last five years. The movie it reminds me of now is Boyhood, with its penetration into the ways a family orbits itself.

It's Cassavetes's film by all the normal markers, but still it owes everything to the performance of his wife Gena Rowlands as Mabel Longhetti. Mabel is married to Nick (Peter Falk) and they have three kids under 10. At first, in a reflexive sort of way, the movie might appear to be courting trouble by taking on the theme of insanity, which is so often the band-aid of fiction. But mental illness in A Woman Under the Influence is not a flimsy way to explain something. It's just the given, and as such the subject itself of the movie, focusing especially on the chaos it produces on the loved ones of the sufferer. In this case, Cassavetes seeks an interesting extra layer by casting his mother and Rowlands's mother as the mothers of Nick and Mabel, respectively. Medicine and attitudes have advanced since the '70s, but the portrait of the Longhetti family in crisis is still perfectly recognizable, with Nick attempting to come to terms with the reality of his wife's condition, fighting through denial and shame, even as Mabel continually loses her grip and blows every chance she gets in polite company.

Thursday, August 09, 2018

"The Malley System" (1967)

Harlan Ellison might seem a bit judgmental in his introduction to Miriam Allen deFord's story in the Dangerous Visions anthology, going on about how old she was to contribute, but I must say a birthdate in 1888 seems remarkable to me too. Though not without its flaws, the story is the best one yet in this collection. I'm going to help you here—or you may consider this a spoiler alert. I thought the structure was a bit clumsy. The first half is disconnected scenes of confusing violence. In the second half they are explained. For me, this meant going back to read the first half again, and then it made much more sense (it's sort of the problem of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury). So I'm going to tell you now. Stand by. The "Malley System" is a form of punishment or rehabilitation for convicted violent felons—murderers, rapists, child molesters, etc. With brain mapping and other technologies sufficiently advanced it's possible to systematically make someone vividly re-experience their crimes again in memory. DeFord explores some of the ramifications in terms of the effects. The treatment is administered daily, and there is a pattern to the responses. The story has a good concept, but I think the best part, once understood, are those scenes from the first half. They are horrific and unnerving. This is sharp, vivid, thoroughly imagined writing. DeFord also wrote crime journalism and other nonfiction, and it shows. Her fantasies are clinical and precise. It's hard to miss a certain amount of rage back of it. In fact, I've almost retreated all the way to Ellison's dumbstruck wonder that material like this could come from a little old lady (Ellison refers to her as a "lady," but I am doing so only ironically—really). If it helps, and it helps me a little, she also wrote for left-wing magazines in the 1920s. That helps me understand where her rage might have been coming from in 1967 as a 79-year-old. Certainly the totalitarian state, with Lachin Malley as its representative—perhaps a figure in the vein of Stanley Milgram—is coolly deconstructed and plausibly responsible. It's chilling, and it's the first story in this collection to live up to the title.

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Monday, August 06, 2018

Sorry to Bother You (2018)

This near-future dystopia takes dead aim at corporatism West Coast style, putting a racial gloss on the Brazil-like nightmares it sees ahead. I don't like Brazil that much in the first place (way too much texture, my usual problem with Terry Gilliam), but the movie Sorry to Bother You reminded me of more was The Circle, a similar attempt last year to signal through the flames of pernicious Silicon Valley culture. Sorry to Bother You is ironic comedy, The Circle is suspense thriller, but the complaints and observations are similar, and familiar. Cassius "Cash" Green (Lakeith Stanfield, Get Out and Selma) is in his late 20 or early 30s and lives in Oakland. He's just landed a job in a telemarketing cube farm at the corporation RegalView. That means he can pay his back rent and help his uncle prevent the bank from foreclosing. His girlfriend Detroit (Tessa Thompson, Creed) is a performance artist with a day job waving signs in front of stores and on busy corners. She is working on a gallery show. The biggest show on TV is I Got the S#*@ Kicked Out of Me—amazingly, that's exactly what it is, a cross between laff-riot TV game show productions and the violence channel in Videodrome. Meanwhile, at the job, Green's work and coworkers are likely familiar to anyone who has put time in on the temp circuit as good-hearted victims of various corporate greed and malfeasance plays. In RegalView's particular line, making sales on the phone is the name of the game. One of Green's coworkers, Squeeze (Steven Yeun, Glenn on The Walking Dead), is trying to organize a union and plans a strike and other actions. But they have poor timing for Cash Green. It turns out he can do his job pretty well when he puts on a white voice, with the help of coaching from another coworker, Langston (Danny Glover). It's actually a lip-synch job, with David Cross, Patton Oswalt, and others providing the white voices. With his white voice, Green is soon on his way to the higher echelons of RegalView as a "power caller," with better offices, a promotion and raise, and the opportunity for ever greener pastures. The only problem is that he is literally marketing B2B for slave labor, as RegalView's biggest client is the corporation WorryFree (please note all the embedded capitalization please), which offers a scheme much like the reverse mortgage only based on lifetime labor. You sign the WorryFree contract and they will keep you working, fed, and sheltered for the rest of your life—it's a promise. Later in the movie, human genetics experiments offer another model for temps, but along about here Green's conscience starts to bother him. It's not that the ideas in Sorry to Bother You are so tired—though they're not that fresh either. It helps that they look way too damn much like reality right now. But in the end I didn't think the movie had enough there there, as Gertrude Stein once said of Oakland.

Sunday, August 05, 2018

Portrait of My Body (1996)

After publishing his large (and essential) anthology of personal essays, Phillip Lopate went to work on his own third collection of them. This time, he says in the introduction, he thought he had to be more careful to include only personal essays—no "literary essays, film and architectural reviews, magazine articles about urbanism and travel, ephemeral 'relationship' pieces.... The dread of all publishing companies is to be caught publishing a random collection of pieces." Accordingly, some of the 13 pieces here are winsomely personal: about shushing in movie theaters, remembering Greenwich Village, and the title piece, equal parts candor and dry wit about his body parts. He likes his legs a lot, for example, because he likes being tall. Many of the pieces touch on his marriage and child. It's a grand joke in his circles that his first collection was called Bachelorhood. His second was Against Joie de Vivre, leading to conjecture this one would be called Against Bachelorhood, a kind of apologia. It may be somewhat awkward for him but I like the sound of the marriage and family here. Speaking of being against things, Lopate notes a theme of "resistance" that runs through these pieces. It's perhaps most explicit in "Resistance to the Holocaust," which is less a personal essay and more a personal opinion—or even polemic—but a useful and interesting one. That's not least because, writing in 1989, he has some air of authority and prescience on the topic. Essentially his argument is that by making the Holocaust a unique event in history, which cannot be compared with other genocides, it must be removed from history and the sphere of critical examination. Lopate is very careful to detach himself from deniers—as a Jew himself, he makes clear he understands all the stakes. It's a subtle point, his resistance. It's more about sentimentality and hagiography obscuring the truth. In some ways, in these various themes of resistance, Lopate comes across more like a basic contrarian, a position with which of course I have much sympathy. If so many people are for it, in the world of human psychology herd instinct, then how can it possibly be any good? At the most fundamental level, this is the attitude all good writers should bring to the party, not just personal essayists. Good stuff again.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Thursday, August 02, 2018

"Riders of the Purple Wage" (1967)

Harlan Ellison makes no bones about it. He says Philip Jose Farmer's story is not just the longest in the Dangerous Visions collection, but the best. You might think Ellison would be more politic about the judgment, but that's Ellison and in many ways his view of the story had wide agreement. Classified as a novella, Farmer's story went on to share the inaugural Hugo Award for Best Novella in 1968 (with Anne McCaffrey's "Weyr Search," not in this collection). For me, Farmer's story might be the most excruciating—80 pages of meaningless action accompanied by groaning literary puns and suspect conservative orthodoxies (as I read them). The title is an obvious play on Zane Grey—too early for the Grateful Dead spinoff band. In the mid-21st-century setting of this tale, the "purple wage" is a guaranteed living income, which everyone in is entitled to as a matter of being born. Government is totalitarian, but appears to be generally benign. Art and creative work are now prized above all else, though it does not appear much different from the celebrity culture we are attempting to live with at the moment. But points for prescience are in order. Among other things, Farmer foresaw what we now call reality TV, with all its potential for desensitized alienation. "Since the solid-state camera is still working," his omniscient narrator observes in the middle of a typically confusing scene, "it is sending to billions of viewers some very intriguing, if dizzying, pictures. Blood obscures one side of this picture, but not so much that the viewers are wholly cheated"—cheated, that is, from witnessing a vicious beating using the self-same blunt object camera that is broadcasting. Farmer could see the coming social reverberations but not how microscopic camera technology would become. I ignored the references to James Joyce's Finnegans Wake as being of no particular good to anyone, and mostly read "Riders of the Purple Wage" as a crypto conservative argument against guaranteed living income, i.e., because most humans can't handle the freedom and are intended to be put to better use by elites. "A discontented, lazy rabble instead of a thrifty working class," as Mr. Potter scolds George Bailey in It's a Wonderful Life about similar enlightened social policies. But that's not actually what Farmer was after, as he explains in his afterword. In fact, it is the other way entirely. Farmer's afterword offers an eight-point precis of what the story is about—implicit support for a Triple Revolution document that was presented to President Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and called for "large-scale public works, low-cost housing, public transit, electrical power development, income redistribution, union representation for the unemployed, and government restraint on technology deployment" (per Wikipedia). I really wish that had been more clear to me, because I can't bear the thought of going back to read the story again.

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)