Story by Ann Beattie not available online.

Ann Beattie's story takes a theme that is familiar in midcentury American lit—the philandering college professor and his various agonies—and turns it on its head, taking the point of view of one of his long-suffering victims. In this case, it's George and his common-law wife, Lenore, who is 21 years younger than him and with a child by him. She is blindly loyal, but stung to the quick when she overhears George tell another woman that she (Lenore) is "simple." Much that is essential about their relationship is revealed in that slight, but there's more to tell. Lenore believes, or at least is only starting to disbelieve, that time is on her side. She thinks all she has to do is wait and George will marry and provide for her. She concentrates on keeping house, baking bread, and raising the child—there's an unmistakable hippie feel to the way Lenore organizes her life. For his part, George is slipping into dissolution. He was denied tenure and left his teaching post two years previous to this story. Since then, he has been unemployed, living the life of a New England writer in the countryside, though he doesn't appear to be doing much writing. He likes to entertain past students who stop at the house with them on weekends. Lenore sees the evidence of George's unfaithfulness—it is even pointed out to her directly in a scene that is atmospheric if hard to believe. At first her rationalizations make sense—he's a middle-aged man in his 50s. Is he having sex outdoors? But the sex itself is unimportant. He is obviously giving more of himself to these students than he gives to Lenore. As much as anything, this story is about the breakdown of Lenore's denial of that. At this point, personally, I've nearly had it with American stories about philandering college professors, but Beattie's story is moving and unsettling. The situation between George and Lenore is broken, and a little horrifying. On the weekend recounted here, George appears to be more flagrant than usual with a visiting young woman, and something causes her and her friend to break off the visit and leave early, taking off after dark on Saturday. It's unclear what went wrong exactly. What's more clear is that Lenore has suddenly realized, which I guess makes this an epiphany story, that she can't count on George for a future. He is 55. She is 34. They have a child. The story dwells deep inside Lenore, with huge blocks of paragraphs on her thoughts. Even in her clarity Lenore is something of a muddled person. The strongest sense of her is incoherent pain and resentment. As troubled as she is, you can't help sympathizing with her. Bleak but effective.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Saturday, July 30, 2016

Elysium (2012)

I suppose it's fair to call this the worst album the Pet Shop Boys ever made, though personally I still haven't warmed much to Fundamental either. I think I might even like Elysium a little more, on a per track per capita basis. But the general air, as befits its title, "the abode of the blessed after death," stubbornly remains drear sanctimony. "Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens"—that applies here. But the good bits undercut any implicit message of eternal happiness, empty or otherwise, and do so quite specifically. "Invisible," for example, which is about life after 50 and/or in heaven—the life of a ghost, that is—takes umbrage with the natural course of indifference: "Is it magic or the truth? Strange psychology? Or justified by the end of youth?" The answer, according to this album, appears to be yes, probably the latter. The depredations of youth upon age are often the point here, occasionally to comic effect, as on "Your Early Stuff," a thorough dressing-down in a random mocking kinda sorta fan encounter in public: "Those old videos look pretty funny. What's in it for you now? Need the money?" We've been here before with lyricist Neil Tennant but he's usually more upbeat about at least holding his own in these confrontations (perhaps first in "Young Offender," from 1993). He seems more resigned now to losing, as detailed in the song "Winner" (or, that is, as detailed in the feeling of it). There are good excuses to offer for much of this album—good grooves, good jokes, good will—but by the second half I admit I'm about crying uncle. The jokes too often fall flat and the pathos feels like mere self-pity. "Hold On" manages the feat of both at once with the feebly ironic refrain, "There's got to be a future, or the world will end today." But then, speaking of ends, the very last song, like out of nowhere, turns out to be my favorite Pet Shop Boys song in I don't know how long—probably that Eminem stunt on Release. "Requiem in Denim and Leopardskin" fits the intended mood of the album better than anything else here by far—the Pet Shop Boys can be sublime when they chase down these tender feelings of the sweet fleeting moments, and at least they manage it better late than never on this album. The song is a knockout, and somehow puts me in mind of scenes from Mary Gaitskill's skillful novel Veronica, which is built out of memories from within a similar place of elysium, nirvana, paradise, kingdom of glory—the place one arrives at by a death of one kind or another.

Friday, July 29, 2016

Menace II Society (1993)

USA, 97 minutes

Directors: Hughes Brothers

Writers: Hughes Brothers, Tyger Williams

Photography: Lisa Rinzler

Music: Quincy Jones III

Editor: Christopher Koefoed

Cast: Tyrin Turner, Jada Pinkett Smith, Larenz Tate, Ryan Williams, Vonte Sweet, MC Eiht, Arnold Johnson, Marilyn Coleman, Clifton Powell, Samuel L. Jackson, Charles S. Dutton, Bill Duke, Too $hort

Identical twins Albert and Allen Hughes made music videos for Tupac Shakur, Tone Loc, and others before embarking on Menace II Society, which they made when they were not even yet 21. The youth shows in some obvious ways, such as the blatant mimicry of Goodfellas, a picture that deeply informs this one's style and themes, and in other occasional clumsy notes. What shows even more, however, is the prowess with mood and setting, an uncanny ability to capture the life of African-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles during that time. I wasn't there, but it feels like real life. We see people of good will living with one another and trying to get along, as well as the desperation and brutality of much of its youth, who are visibly suffocating by the limitations imposed on them all.

Very early, and more than once, the movie slips on documentary garb to inform us in the background and invoke Watts 1965 and Los Angeles 1992. These are the things our characters know, grew up on, live with. More than anything, Menace II Society tells a great human story of the struggle to survive. In fact, one of its most potent scenes is about exactly that, when Charles S. Dutton as a wiser elder, Mr. Butler, counsels our main man and narrator, Caine (Tyrin Turner), and his best buddy O-Dog (Larenz Tate), as follows: "Being a black man in America isn't easy. The hunt is on. And you're the prey. All I'm saying is—survive." Allen Hughes put it another way when the picture debuted at Cannes: "If you hate blacks, this movie will make you hate them more."

Directors: Hughes Brothers

Writers: Hughes Brothers, Tyger Williams

Photography: Lisa Rinzler

Music: Quincy Jones III

Editor: Christopher Koefoed

Cast: Tyrin Turner, Jada Pinkett Smith, Larenz Tate, Ryan Williams, Vonte Sweet, MC Eiht, Arnold Johnson, Marilyn Coleman, Clifton Powell, Samuel L. Jackson, Charles S. Dutton, Bill Duke, Too $hort

Identical twins Albert and Allen Hughes made music videos for Tupac Shakur, Tone Loc, and others before embarking on Menace II Society, which they made when they were not even yet 21. The youth shows in some obvious ways, such as the blatant mimicry of Goodfellas, a picture that deeply informs this one's style and themes, and in other occasional clumsy notes. What shows even more, however, is the prowess with mood and setting, an uncanny ability to capture the life of African-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles during that time. I wasn't there, but it feels like real life. We see people of good will living with one another and trying to get along, as well as the desperation and brutality of much of its youth, who are visibly suffocating by the limitations imposed on them all.

Very early, and more than once, the movie slips on documentary garb to inform us in the background and invoke Watts 1965 and Los Angeles 1992. These are the things our characters know, grew up on, live with. More than anything, Menace II Society tells a great human story of the struggle to survive. In fact, one of its most potent scenes is about exactly that, when Charles S. Dutton as a wiser elder, Mr. Butler, counsels our main man and narrator, Caine (Tyrin Turner), and his best buddy O-Dog (Larenz Tate), as follows: "Being a black man in America isn't easy. The hunt is on. And you're the prey. All I'm saying is—survive." Allen Hughes put it another way when the picture debuted at Cannes: "If you hate blacks, this movie will make you hate them more."

Sunday, July 24, 2016

The Shape of Things to Come (2006)

Somehow I drifted away from Greil Marcus after the 21st century started. As a friend says—the same friend who urged me to take a look at this—"Greil Marcus loves finding great importance in small things." I take that as a good thing and I'm glad I checked this out. Sub-billed as "Prophecy and the American Voice," it focuses on John Winthrop (English Puritan lawyer and cofounder of Massachusetts), Philip Roth (American Jewish novelist), David Lynch (Montana filmmaker), and David Thomas (Cleveland rock 'n' roller), along with the usual assorted sundry. I like Marcus's chosen lifestyle / profession of sitting in his room and thinking of ideas, making connections between the music and art and books he reads, looks at, and listens to. It often means many things are coming up at once and he can build charmingly intricate balancing acts talking about them all at once, seemingly unrelated but relentlessly connecting the dots—and really connecting them. I loved his deep dive on the Philip Roth novels American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain, along with Roth's American dystopia, The Plot Against America. My view on Roth is slightly different, favoring Sabbath's Theater as his masterpiece, which Marcus does not mention. David Lynch gets perhaps the lion's share of attention in this collection, with two sections devoted to two of Lynch's most controversial movies, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway. Marcus does much to illuminate both of them, though unlike many I was already something of a long-time convert to the Twin Peaks movie, which I think sometimes could be Lynch's best. I'm curious but I'm not sure how this long piece on it is taken by the typical Lynchian, just as I'm not sure what a typical Lynchian even looks like. What I like best about Marcus are his deep preoccupations with the things of strange beauty. In some cases, as with the Sex Pistols and David Lynch, I arrived there my own way. In other cases, as with Elvis Presley, Marcus made me see things I never had before. The Shape of Things to Come was a little more like the first for me. I especially enjoyed seeing what he has to say about Roth and Lynch. For anyone who likes Marcus.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Monday, July 18, 2016

The BFG (2016)

I can't blame anybody but myself for this pick. I trusted director Steven Spielberg's name on it and very little else I heard or saw. The comparison is frequently made with E.T., but this is not very much like E.T., although the Extra-Terrestrial in that one, and the Big Friendly Giant in this, may have something of a resemblance and the same amiable dispositions. The BFG lives on its special effects, of course, and much less so on the story, though it comes from Roald Dahl (whom I know only by general reputation). These days, the hero is always a plucky girl rather than boy, which is probably as it should be. I note it only in passing. Her name is Sophie (Ruby Barnhill), she is an orphan already old for her years, and she's very likable. An insomniac, one night she observes the giant skulking around London. When he notices her watching him he kidnaps her and takes her to Giant Country. Sophie dubs him the BFG. It turns out he's the only vegetarian in a crew of human-eating giants. Somehow the Queen of England becomes involved. It gave me a pain. I don't care much for royalty, even less when they are convenient to a narrative. The BFG is family-friendly mostly because the BFG (Mark Rylance in CGI) is such a kindly gentle figure. There is a fair amount of gluttony and other sins on the part of the rest of the giants, and multiple scenes built out of fart jokes. Look, I don't have anything against fart jokes. But while The BFG can be funny, it's never funny enough. And it's warm but not quite warm enough. Maybe that's the CGI. It takes the suspension of disbelief a little too much for granted. Among other things, the BFG collects dreams in jars, which becomes a significant plot element. Yes, you heard me, dreams in jars. I saw this at a morning show the day after the 4th of July (which would make it the 5th of July). Families were in attendance and a good time was had by all, as far as I could tell, but they also felt perfunctory and uninvolved, as if still a little dazed by fireworks and the long day before. Spielberg knows how to charm with film in his sleep, and I suspect that might be what he attempted here. I didn't say he could always charm with film in his sleep. The effects are solid, though nothing is new. For example, the first we see of the BFG is a shadow on a building, which directly recalls the first we see of a UFO in the final cut of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a shadow on a truck and the moon-soaked countryside. Spielberg has been using that trick and others for decades. I didn't see The BFG in 3D, which might have helped with the dreams in jars thing. Unless you're a family, move along. Nothing to see here.

Sunday, July 17, 2016

"The Lesson of the Master" (1888)

Preparing to embark on what turned out to be an abortive career as a man of the theater in the early 1890s, Henry James devoted much of his work then to contemplations of the artist's life and commitment. This long story may be the truest vision because it is about novelists rather than stage actresses or portrait painters. The master in this story, Henry St. George, is a well-established British novelist whose work has been falling off. I have no idea who it's modeled on, if anyone. James may have intended it to resemble no one in particular, as after all it's something of a failing writer. Paul Overt—what a name—is the student, a promising younger writer. They are introduced by a woman named Marian Fancourt, in whom Overt takes an immediate interest ("falls in love with"). Yes, once again the primary concern of all appears to be who the single characters will marry, but it's used very well here. St. George has some idea his work has diminished, and believes it's related somehow to his marriage, which is a happy one. In the central scene of the story St. George seriously counsels Overt not to marry if he wants to fulfill his literary talent. St. George sees it as nearly a direct exchange—happiness in marriage for artistic accomplishment. Overt immediately accepts his advice and goes to the Continent for two years, spending his time mostly alone and writing a masterpiece. Upon his return to London, Overt discovers various improbable things have happened. I'll let you discover them on your own, as they are something of a surprise, clearly intended to illustrate further the themes of the story. James never married, declaring himself a bachelor. It's also possible he was gay. He seems to understand very well a certain dynamic tension between primary relationships and creative work. It's possible this story is a little too programmatic in the way it outlines the problem, but it also has a very good handle on it, which in many ways I think makes this one of the most important pieces in his career. It's not subtle, but its material is a lot better and more pointed than, for example, The Tragic Muse, which also bears the themes. It may speak well to James that he was so relatively reticent in writing a story about writing stories—that would be more of a 20th-century problem—but it's obvious in this story that writing fiction was the creative life he knew, not theater.

"interlocutor" count = 2 / 63 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

"interlocutor" count = 2 / 63 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

Saturday, July 16, 2016

This Is The Sonics (2015)

The first album in 35 years from the classic garage-rockers of Tacoma, Washington, and the first batch of new material in even longer, is surprisingly good. Let's start with that, because I'm not sure how to put this across. I mean, it's really good. Behind the bland statement of judgment is a short and intense history of one year of jumping up and down and all around while it plays, playing it a few times in a row many days (the 12 songs come in around 35 minutes, so it's short), and stuff like that. Time has not dimmed them. If anything, it has burnished the rock 'n' roll attack made out of a saxophone, keyboards, guitar bass drum thrashing, and half-demented lyrical themes, with bluesy rough manners and a heavy rapid-fire bludgeon that somehow floats and rises at will. It follows naturally from the first two album, Here Are The Sonics (1965) and Boom (1966)—and that seems to be exactly the audacious attempt. Kudos to them for pulling this off. Some credit has to go to producer Jim Diamond (Dirtbombs, White Stripes), who obviously knew how to record them. But this is all Sonics. It's essentially the same crew, the same sound, and the same mindset behind "The Witch," "Psycho," "Boss Hoss," "Strychnine," and all of it. I saw them in Portland a year ago, where visually they looked more likely to be found on the tee box of a golf course, except wearing black leather instead of cardigans. But the music bawled out commandingly. The bottom is sludgy, almost murky, with rock-solid tempos, which are geared just back of high frenzy, and propulsive. On top of that they pile raunchy old blues figures, which are easily sensed in the titles: "I Don't Need No Doctor," "Bad Betty," "I Got Your Number" (which turns out to be 6-6-6), and "Livin' in Chaos." It's a slight shift in emphasis away from psychos and strychnine, but they have already established they know from that. In fact, "Livin' in Chaos" offers a bridge to another set of themes they're chasing down here, perhaps most surprising and heartening for me. Namely, some concerns about where we are and where we are headed. "Save the Planet" addresses it with typical cheek—"Save the planet, it's the only one with beer," goes the chorus—but it's still called "Save the Planet," and coming from oldsters now likely well familiar with the ins and outs of drawing Social Security, I appreciate the sincerity of the sentiment. They don't want to perish any more than any of the rest of us, though all they can do is rock. But if rocking is truly all they can do (and I suspect it isn't if they have reached their present ages), they sure as hell can do that well.

Monday, July 11, 2016

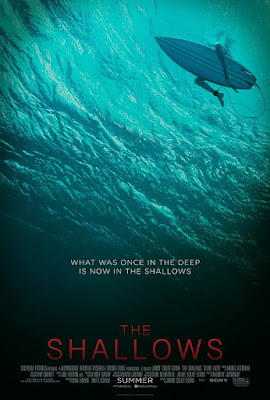

The Shallows (2016)

The Shallows comes with a bunch of obvious debts, most obviously to Jaws but also to more recent movies such as The Descent or 127 Hours. Blake Lively is Nancy, who has arrived at a personal crisis, dropped out of medical school, and journeyed to the isolated beach in Mexico where she was conceived. Her mother is dead of a long slow disease, which is also probably what set Nancy's crisis in motion. At any rate, she's also a surfer and soon takes to the waves. These early scenes are spectacular, fun, and kinetic, like all good surfing footage. But then a darned shark shows up—a great white, no less—and that's it for the good times. Nancy finds herself with a serious flesh wound that keeps bleeding, stuck on a rock 200 feet from the shore, and with the shark circling her. I expected to be bored with this and went looking for jokes to make fun with, but it's actually pretty good for what it is. Director Jaume Collet-Serra and screenwriter Anthony Jaswinski make it more of a classic man vs. nature adventure / survival story than the kind of raw phobia yarns in the vein of horror that Jaws spawned. Not that The Shallows doesn't have its moments of shock cuts and gore. This is a carnivore we're talking about. And, yes, in this story of buoys and gulls, there are points beyond credulity for me, toward the climax. Mostly it stays on track and offers up a pretty good ride. One winning point always is brevity, and this one comes in under 90 minutes. A lot of things can be more fun at that size. I have read complaints about white women who live and Mexicans who die, and it's true that's an unfortunate aspect of this story. Ultimately I think it all works together as a tidy clockwork thriller that's usually not overreaching itself. All the parts fit together nicely. The backstory is cheesy—dead mother, cancer, etc.—but also serves to raise the sympathy quickly and keep things moving. There's even a funnee aminal, a seagull, who is probably the most likable character of all. More cheese, of course, but I have to say, fully expecting otherwise, that I spent an hour and a half caring quite a bit about this skilled woman surfer and that bird, stranded on a rock.

Sunday, July 10, 2016

Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968)

In 1968, Norman Mailer was 45 years old, with six children, and married to his fourth wife. These facts are mentioned more than once in his reports on the American political conventions of that year. He had established his bona fides for the assignment already in 1960 and 1964. But 1968 remains a unique year in the history of politics, American or otherwise—much like 2016 appears to be, now that you mention it. The Democratic convention in Chicago went well beyond the bounds of a typical convention in a presidential election year, historically so, and Mailer was well primed to cover it from his book of earlier that same year, The Armies of the Night, a report on the antiwar March on the Pentagon in 1967. His political analysis is sharp and penetrating on both sides, Republican and Democratic, with a firm understanding of the various realities on the ground, over which he heaps his weird brand of huff and puff metaphysics. It's entertaining and often enlightening. To understand the '60s, which is probably impossible anyway, you should read a lot of books, not just this one, but this should be one of them. So much of the period is neatly compressed into it—hippies, cops, and radical politics, which are just the starting points for digressions. Mailer's middle-aged hipster is one of the better vantages for understanding certain crucial aspects, such as the enduring irrational love for all things Kennedy, the track of the civil rights movement, then giving way to the antiwar movement, both increasingly radicalized, and above all the appalling levels of violence. The collapse in all order for those days in Chicago is shocking to read about now. Mailer documents it well, depending on the reports of others as well as his own experiences. He does so through the haze of a white man's middle-aged anxiety, which works as often as it does not. His reluctance to wade in and take a beating is vivid and well-founded, but comes off a little rationalizing, insular, and ultimately tiresome. In retrospect, it highlights white privilege by showing the reality of a choice others don't have. Today, still, most white people do not often have to face such dilemmas. But these existential questions—notably, do I take a police beating, and even die, for the sake of a principled show of resistance to authority—amount, as much as anything, to the '60s in precis. Obviously, in July 2016, we know they are still sadly very much in effect.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, July 08, 2016

Amarcord (1973)

"I Remember," Italy / France, 123 minutes

Director: Federico Fellini

Writers: Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra, Gene Luotto

Photography: Giuseppe Rotunno

Music: Nino Rota

Editor: Ruggero Mastroianni

Cast: Luigi Rossi, Bruno Zanin, Pupella Maggio, Armando Brancia, Magali Noel, Stefano Proietti, Ciccio Ingrassia, Giuseppe Ianigro, Josiane Tanzilli, Maria Antonietta Beluzzi, Gennaro Ombra

For the most part, director Federico Fellini's work after the 1950s is an acquired taste that I have not yet acquired. I've complained about and/or danced around this previously (see 8½, La Dolce Vita). I like specific scenes, sometimes very much, but the loose and instinctual way Fellini executes his pictures tends to leave me impatient for a more to hang onto. After a couple tries, I recently found more than usual to like in Amarcord. It's in his characteristic later style, but that somehow works better here. "Amarcord" is a phonetic spelling of a term in the relevant Italian dialect that translates as "I remember." It thus announces itself as a memoir film, episodic, random, and idealized by definition, built from the stuff of memories, and childhood memories at that, of a specific time and place.

That time and place, however, happens to be 1930s Fascist Italy. You can't help reacting when you first see whimsy and nostalgia slathered on an era so reviled now. But Fellini is not doing any kind of gloss job here, which helps make the picture work. Mussolini and his followers tend to be ridiculous, but they are also clearly menacing (think Donald Trump rallies), and more than one long scene is devoted to reckless depredations of Fascist Party authorities in the era. Il Duce himself even makes an appearance at one point, largely as a buffoon. Fellini's artistry is notably evident in his skillful use all through the movie of mists, fog, road dust, gas fumes, and other visual obscurities functioning like impaired memory, a subtly effective way to remind us that this is a film of memories and that memory is unreliable.

Director: Federico Fellini

Writers: Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra, Gene Luotto

Photography: Giuseppe Rotunno

Music: Nino Rota

Editor: Ruggero Mastroianni

Cast: Luigi Rossi, Bruno Zanin, Pupella Maggio, Armando Brancia, Magali Noel, Stefano Proietti, Ciccio Ingrassia, Giuseppe Ianigro, Josiane Tanzilli, Maria Antonietta Beluzzi, Gennaro Ombra

For the most part, director Federico Fellini's work after the 1950s is an acquired taste that I have not yet acquired. I've complained about and/or danced around this previously (see 8½, La Dolce Vita). I like specific scenes, sometimes very much, but the loose and instinctual way Fellini executes his pictures tends to leave me impatient for a more to hang onto. After a couple tries, I recently found more than usual to like in Amarcord. It's in his characteristic later style, but that somehow works better here. "Amarcord" is a phonetic spelling of a term in the relevant Italian dialect that translates as "I remember." It thus announces itself as a memoir film, episodic, random, and idealized by definition, built from the stuff of memories, and childhood memories at that, of a specific time and place.

That time and place, however, happens to be 1930s Fascist Italy. You can't help reacting when you first see whimsy and nostalgia slathered on an era so reviled now. But Fellini is not doing any kind of gloss job here, which helps make the picture work. Mussolini and his followers tend to be ridiculous, but they are also clearly menacing (think Donald Trump rallies), and more than one long scene is devoted to reckless depredations of Fascist Party authorities in the era. Il Duce himself even makes an appearance at one point, largely as a buffoon. Fellini's artistry is notably evident in his skillful use all through the movie of mists, fog, road dust, gas fumes, and other visual obscurities functioning like impaired memory, a subtly effective way to remind us that this is a film of memories and that memory is unreliable.

Saturday, July 02, 2016

Ummagumma (1969)

Pink Floyd's fourth album was a double-LP package, with one record devoted to live recordings of four songs and the other to individual studio projects by each of the four principals at the time (David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Roger Waters, and Richard Wright). I've never much connected with the studio projects, which seem more aimless and empty ego-driven exercises of some kind. The live album is open to criticism too—the songs are simplistic, the playing rudimentary, and the recording not particularly inspired. Nonetheless, the performances mark a kind of fantasized rock concert ideal that appealed to me then, and still appeals to me now, and not as nostalgia. What I mostly like are the simplistic songs and the rudimentary playing, almost perfectly unself-consciously capturing the essence of a late-'60s rock concert, at least as I understand them from the stories. There's a lot of play with dynamics on all this music, as every song stretches out eight minutes and more. They bring it down to soft bass notes, softly brushed guitar chords, casual keyboard notes or chords, and drums barely tapped and poked at. Then it becomes loud again, with sound arriving like a tidal wave. In many ways they are inventing a kind of rock staple. The ideas are not yet fully developed but the excitement of their discovery makes it irrelevant. It's easy to imagine a crowd listening to this sitting on a filthy floor and zonked out of their minds. Among other things, it's excellent stoner fare. There is a drum solo, of course. Syd Barrett's "Astronomy Domine" gets the honors for kicking it off, but my favorite of the four songs is Roger Waters's spooky "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun," a strange and doomy ride aboard a spaceship with astronauts who sound hypnotized. Their mission: see title. (Maybe this is post-HAL fallout from 2001?) Another song with a descriptive title, "Careful With That Axe, Eugene" is a collaboration of all four of them. It reminds again of Pink Floyd's flirtations with certain tropes of horror cinema, also seen, for example, two years later in Meddle's opening track, "One of These Days" (you have to pick it out of the production but the monster voice there is saying "One of these days I'm going to cut you into little pieces"). I'm assuming this is more of Roger Waters's lifelong anger management sorting-out? At any rate, "Careful With That Axe, Eugene" only has the title phrase and some uncomfortable screaming to explain itself, which is no explanation at all. Mostly it's a moody arguably overlong guitar showcase. I am not making that argument, though I could do without the screaming. At worst, the set is merely quaint, lightweight, and silly. You bet a song like "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" is easy to mock. I swear it works, however. I've been listening to it all my life.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)