USA, 100 minutes, documentary

Director: Davis Guggenheim

Photography: Davis Guggenheim, Robert Richman

Music: Michael Brook

Editors: Jay Cassidy, Dan Swietlik

Cast: Al Gore

I had better make clear first that I'm on board with the views of the overwhelming majority of scientists today that global warming is real, potentially devastating, and a result of our own activities, and that there are steps we can take to moderate its effects. I was on board with it before a frame of this was shot, or even conceived, mostly because a majority of scientists today have been so perfectly clear about it—and, not incidentally, because Al Gore has been running around yapping about it since the '70s. Looking at An Inconvenient Truth now, more than six years beyond its release, remains for me little more than an exercise in preaching to the choir.

But could it ever have been anything else? I never was the intended audience. That would be the sober chin-strokers who aren't yet convinced that global warming has fit itself into various business models with sufficient deference. The result, as with the discourse in this election cycle just past, is that more often I feel like a bystander and witness to an interminably inane dialogue which of itself holds our world in peril, fiddling while Rome burns. I find myself anxiously wondering on every point, "Does that make sense to them? Is this getting through to them? What don't they understand about this?"

Friday, November 30, 2012

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Suburbs, "Love Is the Law" (1984)

(listen)

At the time, focused on other things (Prince, Replacements, Husker Du, Bruce Springsteen), I gave this Suburbs song and album a whole lot of short shrift. I had occasion to hear it again, with fresh ears as it were, shortly after I found out early in 2010 that founding member, guitarist, and graphic designer Bruce C. Allen had died. Bruce (and bassist Michael Halliday) went to the same high school as me and I knew them both to hang around with now and then. The rest of the band grew up in my home suburb of Minnetonka. And they weren't the only ones starting bands. Arguably Twin Cities punk/New Wave of the '70s started with the Suicide Commandos (setting aside Skokie & the Flaming Pachucos, more of a key influence), which also included a member I went to high school with, bassist Steve Almaas, and the rest of the band from Minnetonka. The Suburbs turned out to be an awesome live act, along about 1981 and 1982, and some of that made it to their albums, notably In Combo and Credit in Heaven. Good reviews helped cast a hopeful glow too but already interest in New Wave was on the wane, unless maybe it was British. So the Suburbs just missed. When I recall some of the epic nights I had with them, usually at the Cabooze, which was close to where I lived, and hear what a rousing, supple, exciting shout of a thing this song is, and even remember some details of hanging out with Bruce way back—his bedroom was a detached structure from his family's house, making it more like a cool kid's fort for playing albums loud and honking joints, and he'd sit there doing both with a guitar in his lap—it makes me both sad and happy. I know it's projection of some kind, purely personal, but I hear all that in this song now.

At the time, focused on other things (Prince, Replacements, Husker Du, Bruce Springsteen), I gave this Suburbs song and album a whole lot of short shrift. I had occasion to hear it again, with fresh ears as it were, shortly after I found out early in 2010 that founding member, guitarist, and graphic designer Bruce C. Allen had died. Bruce (and bassist Michael Halliday) went to the same high school as me and I knew them both to hang around with now and then. The rest of the band grew up in my home suburb of Minnetonka. And they weren't the only ones starting bands. Arguably Twin Cities punk/New Wave of the '70s started with the Suicide Commandos (setting aside Skokie & the Flaming Pachucos, more of a key influence), which also included a member I went to high school with, bassist Steve Almaas, and the rest of the band from Minnetonka. The Suburbs turned out to be an awesome live act, along about 1981 and 1982, and some of that made it to their albums, notably In Combo and Credit in Heaven. Good reviews helped cast a hopeful glow too but already interest in New Wave was on the wane, unless maybe it was British. So the Suburbs just missed. When I recall some of the epic nights I had with them, usually at the Cabooze, which was close to where I lived, and hear what a rousing, supple, exciting shout of a thing this song is, and even remember some details of hanging out with Bruce way back—his bedroom was a detached structure from his family's house, making it more like a cool kid's fort for playing albums loud and honking joints, and he'd sit there doing both with a guitar in his lap—it makes me both sad and happy. I know it's projection of some kind, purely personal, but I hear all that in this song now.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

The Exorcist (1973)

#7: The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973)

It might be fair to say that Stockholm syndrome has something to do with this pick. The Exorcist is usually the first place I go in my mind when thinking about best/favorite horror pictures. It wasn't the first in which I had the experience of surviving something and feeling notably alive after a very bad scare. In terms of the movies, that would probably be The Wizard of Oz, and later on Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Carrie, Suspiria, the various Cronenbergs, The Evil Dead, even A Nightmare on Elm Street. But The Exorcist is the most scared that any movie ever made me. Maybe that's something about my age when I saw it, in my late teens.

I'm not sure I made it all the way around to the catharsis part with The Exorcist either, certainly not after the first time I saw it. That was the week of its release, which means I might have seen the original with the subliminals. It was in a big old barn of a theater in downtown Minneapolis on a weeknight, packed full, with people sitting up front laughing at it like hyenas, and the rest of us behind them reduced to gelatin—at least my friend and I were. I made it out of that theater half traumatized. People were talking in comments here the other day about stunners. The Exorcist ranks among mine. I'm not any more afraid of crashing to my death in an airplane than I am of evil and Satanic forces stealing my soul (or body)—which is to say, maybe a little, I love Fearless and Rosemary's Baby too. But not so much that it keeps me up at night. Except this movie kept me up nights.

It might be fair to say that Stockholm syndrome has something to do with this pick. The Exorcist is usually the first place I go in my mind when thinking about best/favorite horror pictures. It wasn't the first in which I had the experience of surviving something and feeling notably alive after a very bad scare. In terms of the movies, that would probably be The Wizard of Oz, and later on Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Carrie, Suspiria, the various Cronenbergs, The Evil Dead, even A Nightmare on Elm Street. But The Exorcist is the most scared that any movie ever made me. Maybe that's something about my age when I saw it, in my late teens.

I'm not sure I made it all the way around to the catharsis part with The Exorcist either, certainly not after the first time I saw it. That was the week of its release, which means I might have seen the original with the subliminals. It was in a big old barn of a theater in downtown Minneapolis on a weeknight, packed full, with people sitting up front laughing at it like hyenas, and the rest of us behind them reduced to gelatin—at least my friend and I were. I made it out of that theater half traumatized. People were talking in comments here the other day about stunners. The Exorcist ranks among mine. I'm not any more afraid of crashing to my death in an airplane than I am of evil and Satanic forces stealing my soul (or body)—which is to say, maybe a little, I love Fearless and Rosemary's Baby too. But not so much that it keeps me up at night. Except this movie kept me up nights.

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Women in Love (1920)

I read Women in Love voluntarily, on my own, prompted by a couple of people who separately, in a month's time, remarked how much they liked it. Whether it was the expectations thus engendered or whatever, I wasn't much impressed. D.H. Lawrence seems to me to be a writer who leans very hard into expressing the inexpressible by expressing over and over again how inexpressible it is. The profound and inviolate earth, etc. William Faulkner is another writer who indulges this, though I think he is a bit more successful with it. (For that matter, I'm pretty sure I do it too and so have little to complain about as I am hardly in the same league as either.) At its best, as with Faulkner, it can be positively hypnotic, describing the indescribable by describing so vividly everything around it, like the technique of defining and drawing negative space in sketching. I will give Lawrence this: it's a pretty big book and I was never tempted (well, never too tempted) to abandon it. But I had a hard time relating to any of the characters because I had a hard time relating to their experience of sexuality, which in many ways is all that it's about. Certainly I can see how it might be taken as daring and provocative, certainly for its times. But in these times I can't help finding it all a little outdated, even antiquated. I really don't mean to be complacent, but it seems to me that women, at least in much of the West, are more enabled now to resist the effects of the kinds of sexual repression in Lawrence's story—to never have to suffer them in the first place in some cases. Sexual activity is usually a given for adult women. I know it's likely that I'm missing some basic point about D.H. Lawrence in this novel. But a rural British village in the early 20th century doesn't offer me many ways in. In some ways it reminds me of the folks I've known from Western North Dakota. When it's you and the land and your family and your community, it's different from being surrounded by thousands and millions of people. And when you're the aristocracy—well, then. In fact, for me that was the most interesting part of the book, all the sideline various ins and outs of the labor relations and struggles.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 24, 2012

Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994)

Part II, the sequel: The grand Pavement experiment continues. There are a couple of EP releases between this album and the first, and I recall liking at least one of them (Watery Domestic) quite a bit. Scanning through the reviews at various sites (Christgau and Amazon customers, chiefly), I see that Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain is widely taken as essentially more of the same, somewhat tidied up and improved with melody and experience. There's nothing there I can disagree with—I certainly don't see it as any better or worse than the debut. And I hear it and listen to it in the same way, the entire album as given, sequencing and all, which is distinguished across its 42+ minutes by hooks and moments that seem less part of any song than of the album itself abstractly, as zeitgeist, weltschmerz, or whatever suitably Germanic phrase pleases you (because it somehow seems like it should be Germanic). The second half of "Stop Breathin," as an example, offers up a pleasant guitar interplay instrumental that doesn't seem to have much to do with the first half, except I guess conceptually. It sounds like the kind of thing that gets worked out in rehearsal, various inspirations caught and braided neatly together, and every time it comes along it makes me happy. One song, "5-4=Unity," doesn't sound much to me like anything else on the album or indeed in their catalog, another hooky instrumental, this time with a bit of cheek, like something out of a spy movie. I generally like Steve Malkmus's yelpy singing, especially when the band comes surging in behind him (as on "Gold Sounds"). I like the creaky sound of the band, which feels like it is holding it together but barely, because it makes the moments of inspiration jump out that much more. Pavement on these albums reminds me of bands like the Neats or even the Feelies, incorporating tentativeness into the very structure of what they do—because, presumably, so much of their lives as indie rock icons (not that they intended it, but the mantle was thrust on them fully by this point) are plugged into that sense that nothing is sure, all is tentative. Sometimes, as on the chorus of "Range Life," it feels like certainty has finally arrived and the clear-sightedness of it is just invigorating and warming. But here's what worries me. I'm getting to all this by way of a self-imposed homework assignment for my blog, "assess Pavement albums in 400 words," and the problem is that I have rarely been motivated otherwise over all these years to pay them much attention. Maybe time for me to call it a day on this band.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Goodfellas (1990)

USA, 146 minutes

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers: Nicholas Pileggi, Martin Scorsese

Photography: Michael Ballhaus

Editors: James Y. Kwei, Thelma Schoonmaker

Cast: Robert DeNiro, Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco, Paul Sorvino, Frank Sivero, Tony Darrow, Mike Starr, Frank Vincent, Chuck Low, Henny Youngman, Jerry Vale, Michael Imperioli, Illeana Douglas, Vincent Gallo, Catherine Scorsese, Debi Mazar, Samuel L. Jackson, Welker White

Goodfellas is the first movie since Mean Streets on which director Martin Scorsese took a writing credit. Somehow that helps me make sense of where I think it fits among his films—on the short list of his best. As brash and kinetic and sustained as anything he has done, it is personal, defiantly anti-formal (all rules delimiting voiceover narration and freeze-frames cavalierly tossed, for example), and a critical twist on the operatics of gangster pictures as we had understood them until then. If, like Pulp Fiction, it now has much to answer for in terms of setting in motion clichés and other noxious pop culture memes still calcifying (looking at you, retro lounge), this original suffers none of their deficiencies.

In fact, that is one of its great surprises again and again. I am always impressed by the pure crackling energy of Goodfellas. Somebody in the special features on the DVD remarks that no one flipping through TV channels and landing on Goodfellas has ever changed the channel again until the movie is finished. It's true that it is insanely engaging, with a powerful narrative current. Part of the trick is the shift in focus, which moves away from the wood-paneled and predictably corrupting counsels of power of the Godfather franchise (or even De Palma's Scarface) and instead concerns itself solely with the foot soldiers of the criminal enterprise, out hustling to earn. It's the same sickness of the soul, but now it's Chekhovian rather than Shakespearean.

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers: Nicholas Pileggi, Martin Scorsese

Photography: Michael Ballhaus

Editors: James Y. Kwei, Thelma Schoonmaker

Cast: Robert DeNiro, Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco, Paul Sorvino, Frank Sivero, Tony Darrow, Mike Starr, Frank Vincent, Chuck Low, Henny Youngman, Jerry Vale, Michael Imperioli, Illeana Douglas, Vincent Gallo, Catherine Scorsese, Debi Mazar, Samuel L. Jackson, Welker White

Goodfellas is the first movie since Mean Streets on which director Martin Scorsese took a writing credit. Somehow that helps me make sense of where I think it fits among his films—on the short list of his best. As brash and kinetic and sustained as anything he has done, it is personal, defiantly anti-formal (all rules delimiting voiceover narration and freeze-frames cavalierly tossed, for example), and a critical twist on the operatics of gangster pictures as we had understood them until then. If, like Pulp Fiction, it now has much to answer for in terms of setting in motion clichés and other noxious pop culture memes still calcifying (looking at you, retro lounge), this original suffers none of their deficiencies.

In fact, that is one of its great surprises again and again. I am always impressed by the pure crackling energy of Goodfellas. Somebody in the special features on the DVD remarks that no one flipping through TV channels and landing on Goodfellas has ever changed the channel again until the movie is finished. It's true that it is insanely engaging, with a powerful narrative current. Part of the trick is the shift in focus, which moves away from the wood-paneled and predictably corrupting counsels of power of the Godfather franchise (or even De Palma's Scarface) and instead concerns itself solely with the foot soldiers of the criminal enterprise, out hustling to earn. It's the same sickness of the soul, but now it's Chekhovian rather than Shakespearean.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Johnny Rivers, "The Snake" (1966)

(listen)

The album pictured above, ...And I Know You Wanna Dance, was one of the first I ever owned, at the age of approximately 11, courtesy of the Columbia Record Club, which I joined in the mid-'60s with my brother as self-styled tycoon paperboys with money to burn. What I didn't know until a recent visit to Wikipedia is that it is actually Johnny Rivers's fourth album traveling under the concept ("recorded LIVE at the Whiskey a Go Go!"). It's the home of the hit single version of "Secret Agent Man," which by itself might make it the most significant of the four. I don't know about that. What I know is that "The Snake," which kicked off the album, plugged into a vaguely toxic gender orientation that appealed to me as an 11-year-old (Rubber Soul's "Run for Your Life" is another, as is much of the Stones' catalog of the mid-'60s, although their music frankly scared me so I didn't become familiar with "Under My Thumb" for many more years)—sneering tough-guy juvenile-delinquent types laying down the law to the ladies. Here it comes in the form of a fable about a poor trusting woman bamboozled by a vicious snake. Yes, that's right, leaving it open to ham-handed interpretations both Biblical and phallic. This may be the best-known song by songwriter Oscar Brown Jr., who elsewise worked eclectically in jazz, civil rights, the theater, and poetry. Rivers is typically in form as one of the great unrecognized rhythm and blues performers (vying for position with his status as one of the great unrecognized singles artists). But needless to say (I hope) I'm less comfortable now with the basic thrust. The real tell, as far as I'm concerned, is the goofy pinched mocking falsetto Rivers employs for the woman's voice, the woman in this story being monumentally dumb of course. There's a lot of bridling yet socially acceptable contempt here, which makes it an interesting period piece if nothing else.

The album pictured above, ...And I Know You Wanna Dance, was one of the first I ever owned, at the age of approximately 11, courtesy of the Columbia Record Club, which I joined in the mid-'60s with my brother as self-styled tycoon paperboys with money to burn. What I didn't know until a recent visit to Wikipedia is that it is actually Johnny Rivers's fourth album traveling under the concept ("recorded LIVE at the Whiskey a Go Go!"). It's the home of the hit single version of "Secret Agent Man," which by itself might make it the most significant of the four. I don't know about that. What I know is that "The Snake," which kicked off the album, plugged into a vaguely toxic gender orientation that appealed to me as an 11-year-old (Rubber Soul's "Run for Your Life" is another, as is much of the Stones' catalog of the mid-'60s, although their music frankly scared me so I didn't become familiar with "Under My Thumb" for many more years)—sneering tough-guy juvenile-delinquent types laying down the law to the ladies. Here it comes in the form of a fable about a poor trusting woman bamboozled by a vicious snake. Yes, that's right, leaving it open to ham-handed interpretations both Biblical and phallic. This may be the best-known song by songwriter Oscar Brown Jr., who elsewise worked eclectically in jazz, civil rights, the theater, and poetry. Rivers is typically in form as one of the great unrecognized rhythm and blues performers (vying for position with his status as one of the great unrecognized singles artists). But needless to say (I hope) I'm less comfortable now with the basic thrust. The real tell, as far as I'm concerned, is the goofy pinched mocking falsetto Rivers employs for the woman's voice, the woman in this story being monumentally dumb of course. There's a lot of bridling yet socially acceptable contempt here, which makes it an interesting period piece if nothing else.

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

Taxi Driver (1976)

#8: Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

It seems like I've been talking about Bernard Herrmann a fair amount recently—he wrote the scores for a good many of Hitchcock's best pictures, including Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho. He wrote the scores for Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 and for a dozen or so episodes each of "Twilight Zone" and the "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour." He even contributed to The Magnificent Ambersons and Citizen Kane. Taxi Driver is the last picture he worked on, shortly before his death toward the end of 1975, and that score is a doozy. The clip of the titles at the first link below suggests how important his work is here to setting the mood and creating the unmistakable feeling of stepping into a dark, mysterious place where not all of the usual rules are going to apply.

You will also, of course, quickly notice that some appreciation must apply to photographer Michael Chapman as well, whose brilliant and eerie first image of the cab from bumper level gliding through the fog is equally affecting, perfectly in synch with the music. And then the fuzzy, lurching, streaming, super-saturated look of the city streets at night that Chapman goes to as needed takes it up another notch. So that gets us approximately two minutes into a film that never once loses its way for nearly two hours.

It seems like I've been talking about Bernard Herrmann a fair amount recently—he wrote the scores for a good many of Hitchcock's best pictures, including Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho. He wrote the scores for Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 and for a dozen or so episodes each of "Twilight Zone" and the "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour." He even contributed to The Magnificent Ambersons and Citizen Kane. Taxi Driver is the last picture he worked on, shortly before his death toward the end of 1975, and that score is a doozy. The clip of the titles at the first link below suggests how important his work is here to setting the mood and creating the unmistakable feeling of stepping into a dark, mysterious place where not all of the usual rules are going to apply.

You will also, of course, quickly notice that some appreciation must apply to photographer Michael Chapman as well, whose brilliant and eerie first image of the cab from bumper level gliding through the fog is equally affecting, perfectly in synch with the music. And then the fuzzy, lurching, streaming, super-saturated look of the city streets at night that Chapman goes to as needed takes it up another notch. So that gets us approximately two minutes into a film that never once loses its way for nearly two hours.

Monday, November 19, 2012

Wrecking Ball (2012)

This has been a fairly constant companion for me a lot of this year, first in the late spring and summer when I had it installed in my car as a feature for a few months, and more lately just letting it come up a lot in the mix. So I'd like to put a good word in for it at this late hour, though no doubt you have already made up your own mind if you are even interested. It's the first time I've lived with a Bruce Springsteen album so intensely since Tunnel of Love (I did try very hard to establish such things with Human Touch, The Rising, and that Tom Joad one too). There's a lot of earnestness to go around here, but this was a good year for feeling earnest, and it's ultimately nice to experience it so clear-sighted, plainspoken, and yet acute too. For example, one of the most prominent themes in this set puts Springsteen at the back of a boulder pushing it up a hill attempting to reclaim Christianity. Seriously, there's a lot of Jesus and the Bible here, not just sweet beautiful strains of gospel (embedded in his DNA as birthright with rock 'n' roll, rhythm and blues, and soul). Personally, I've always been comfortable myself with the conception of Jesus the Christ as first and most immaculate hippie—it makes sense on many different levels. But of course exactly that is profoundly rejected by those carrying the biggest megaphones for Christ these days and I really don’t care to discuss it with them. I take it as just another aspect of this bizarro up-is-down world we seem to be living in now—you mean Jesus really didn't favor the poor over the rich, inherit the earth, eye of a camel, all that jazz, OK, whatever. This is the point where I begin to mumble and look down in these conversations. But there is Mr. Bruce Springsteen (as Randy Newman would say) taking it to them on the very issue, at least as far as I can make out, and it's only one of a bunch of things here that manage to touch me really deeply, as heartfelt and profoundly on point, which he has done before. Here, I mostly just appreciate hearing someone say things like "The banker man grows fatter / The working man grows thin," if only as an affirmation of what I see and feel myself. There's all kinds of basic touchstones of specific experience here. "We've been traveling over rocky ground." "This is my confession / I need your heart / In this depression / I need your heart." "We are alive." Et cetera. And that goes for this too: "If I had me a gun / I'd find the bastards and shoot 'em on sight." I know, I know, it's all role playing in the end with these things, but that's also my point. Signals such as these helped me understand I wasn't traveling alone this year.

Sunday, November 18, 2012

The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (1975)

When I finally got to Maxine Hong Kingston's memoir it was nothing like I expected, and much more. Much more—and much less, too—than an ordinary memoir, the experimental flavor of it penetrates and suffuses and carries away much of the simple factual material. This goes beyond showing how events felt to showing how the unconscious experienced the events, and invented events of its own to absorb the blows of deeply foreign experience. It is full of strange dreams and fears torqued to maximum impact—the anger and sorrow and impossibility of such a transition are preserved almost perfectly, even as the homely details are mostly left behind. Thus, surprisingly, it becomes a story of great spirit encountering the strangely physical. There's not a lot to hang a hat on here—very little directly about language adjustments, ethnic self-awareness and accommodation, neighborhoods, schools, kindly adults. They are there, make no mistake—but their context is fierce and fantastic. One of the great things Kingston does is put the focus on Chinese culture and her heritage. The Western sophistication she has achieved speaks for itself, and is the perfect vehicle for saying what she's got to say. The hardships and privations can be wrecking. A raid, as recalled by Kingston's mother: "The villagers broke in the front and the back doors at the same time, even though we had not locked our doors against them. Their knives dripped with the blood of our animals.... Your aunt gave birth in the pigsty that night. The next morning when I went for water, I found her and the baby plugging up the family well." Unflinching stuff, yet followed by a beautiful and complex tale spun out of her mother's "talk-story" that she lulled her children to sleep with, about a powerful swordswoman and heroine, a shiny brilliant character. A variation of Wonder Woman, to the Western comic book reader. The story is bold and swift and absorbing. The whole book is great.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 17, 2012

Slanted and Enchanted (1992)

I saw Pavement in 1995 or thereabouts and I remember it was a very fine show—roaring loud, seductive, insinuating, with surprisingly powerful currents, and always interesting. I surged with the crowd and didn't want it to end, etc. I'm serious. I was still there pounding for more when the house lights went up. They were great. But shortly after that the mystery about the appeal of this quixotic unit ensued as if it had never been cleared up even for a moment. I find it hard to connect with the albums, even the consensus best, such as this debut. Or maybe I find myself forgetting how to. I've been puzzling over it again trying to figure out something to say about this album which I think meant so much to so many. At one time I felt like I was rotating between separate tribes devoted to My Bloody Valentine, Nirvana, and Pavement—blobs of adoration floating around out there and not intersecting much. On the Venn diagram it would be three distinct circles. They all participated to a certain extent, among many others, in a certain vogue of the time for elaborately disaffected song titles, so here: "Jackals, False Grails: The Lonesome Era," "Zurich Is Stained," "Chesley's Little Wrists," "In the Mouth a Desert," "Summer Babe (Winter Version)," so on so forth, there are 14 songs here. There are certainly hooks, things to grab onto, as I just now noticed one welling up out of the end of "No Life Singed Her," but they don't seem to be occurring within the structure of songs as such. To me, at their best, when I think I might be getting it, they are album artists working in the broad 40-minute scope, with a ground of sound based on ramshackle 2 guitars bass drums+ interplay that's almost not sloppy, and from that emerges this little parade of surprises: a chanted chorus that takes on momentum, lots of guitar riffs finding a way, and often an evident willingness to simply let it all ride, or stop, with breaks for adjustments every two or three minutes, meaning that's how the tracks go by. You don't necessarily wait for a certain song but for moments that aren't always quite where you thought you remembered they'd be, but it's all right because there's something interesting coming along now you'd forgotten. It's never quite what you think it is. The cover art is not misleading, I'll put it that way. At the moment, "Two States" is my favorite song—because it's the one playing.

Friday, November 16, 2012

3:10 to Yuma (1957)

USA, 92 minutes

Director: Delmer Daves

Writers: Halsted Welles, Elmore Leonard

Photography: Charles Lawton Jr.

Music: George Duning

Editor: Al Clark

Cast: Glenn Ford, Van Heflin, Felicia Farr, Leora Dana, Henry Jones, Richard Jaeckel, Robert Emhardt

It's interesting to watch virtually back to back the two movie versions of the 1953 Elmore Leonard story, "Three-Ten to Yuma," made 50 years apart out of the same story—indeed, the same screenplay, as Halsted Welles (who died in 1990) gets first writing credits in both. Many of the same plot points and even scenes and lines of dialogue recur in both. Yet they are two rather different films. The 2007 remake is a remake, first, hallmark of a metastasizing trend of the 2000s (and counting), patching in state-of-the-art action stylings by expanding a good deal, and not unsuccessfully, on the story's middle section. The original eschews a lot of the fancy set pieces of the remake, no doubt in line with budget considerations, instead focusing on the story much more as suspense chamber piece with Rod Serling-level ironies of human foible.

For anyone interested in treatments of Elmore Leonard stories they are a particularly interesting pair, both coming from outside of the '80s and '90s bubble, when Leonard may have been coasting a little on the superstar status he enjoyed. (I need to see Get Shorty and Out of Sight again but I remember them now as bloated and self-satisfied and was definitely underwhelmed.) Both versions of 3:10 to Yuma, however, are worth seeing I think (and then, with me, it's on to catch up with the FX TV show Justified, which I suddenly realize I have been hearing good things about for years now). But if you only have time for one—and I know how that goes, life is short after all—then this 1957 version is your pick. The usual spoiler disclaimer verbiage goes here.

Director: Delmer Daves

Writers: Halsted Welles, Elmore Leonard

Photography: Charles Lawton Jr.

Music: George Duning

Editor: Al Clark

Cast: Glenn Ford, Van Heflin, Felicia Farr, Leora Dana, Henry Jones, Richard Jaeckel, Robert Emhardt

It's interesting to watch virtually back to back the two movie versions of the 1953 Elmore Leonard story, "Three-Ten to Yuma," made 50 years apart out of the same story—indeed, the same screenplay, as Halsted Welles (who died in 1990) gets first writing credits in both. Many of the same plot points and even scenes and lines of dialogue recur in both. Yet they are two rather different films. The 2007 remake is a remake, first, hallmark of a metastasizing trend of the 2000s (and counting), patching in state-of-the-art action stylings by expanding a good deal, and not unsuccessfully, on the story's middle section. The original eschews a lot of the fancy set pieces of the remake, no doubt in line with budget considerations, instead focusing on the story much more as suspense chamber piece with Rod Serling-level ironies of human foible.

For anyone interested in treatments of Elmore Leonard stories they are a particularly interesting pair, both coming from outside of the '80s and '90s bubble, when Leonard may have been coasting a little on the superstar status he enjoyed. (I need to see Get Shorty and Out of Sight again but I remember them now as bloated and self-satisfied and was definitely underwhelmed.) Both versions of 3:10 to Yuma, however, are worth seeing I think (and then, with me, it's on to catch up with the FX TV show Justified, which I suddenly realize I have been hearing good things about for years now). But if you only have time for one—and I know how that goes, life is short after all—then this 1957 version is your pick. The usual spoiler disclaimer verbiage goes here.

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Meat Puppets, "Two Rivers" (1985)

(listen)

I think most Meat Puppets true believers tend to prefer the breakthrough Meat Puppets II over the follow-up, Up on the Sun, which provides the home for this. Fair enough, that's true enough, it's probably the better album, and certainly the bigger and better surprise. But I have to say this is my one favorite song by the band, if forced to pick a single favorite (which, I know, these things never happen). It's another one of those more or less obscurities—never released as a single, always occupying the #11 spot in the sequencing (deep into the vinyl side 2), etc. But wow, once cranked up, it just sparkles—a word I choose deliberately, because "sparkles" is exactly what guitarist/songwriter Curt Kirkwood manages with the beautiful, haunting noise he makes with the guitar, the hook that makes this song, which glitters across the surface passing through like the self-same waters of the title, reflecting sunshine. That sound somehow encapsulates a lot of the themes the whole album implicitly (and explicitly) plays with, hard flat desert sunlight, the feel of an epic landscape, stripped down and harsh, but lushly beautiful with fantastic colors. The geography they lived in and knew. Out of that this Arizona power trio concocted the studious country-inflected groove so familiar from their peak. Remember, the first album was a bit of a hardcore punk-rock exercise. So they covered a lot of ground to finally arrive at this quasi-Grateful Dead quasi-R.E.M. brooding style of feeling one's way through a jam, tightening it up and focusing it sharp. For the moment anyway they are verging on territory of acts such as Neil Young and the Band, tapping deep into veins of American experience in a way that's hard to explain. It's another absolute beauty.

I think most Meat Puppets true believers tend to prefer the breakthrough Meat Puppets II over the follow-up, Up on the Sun, which provides the home for this. Fair enough, that's true enough, it's probably the better album, and certainly the bigger and better surprise. But I have to say this is my one favorite song by the band, if forced to pick a single favorite (which, I know, these things never happen). It's another one of those more or less obscurities—never released as a single, always occupying the #11 spot in the sequencing (deep into the vinyl side 2), etc. But wow, once cranked up, it just sparkles—a word I choose deliberately, because "sparkles" is exactly what guitarist/songwriter Curt Kirkwood manages with the beautiful, haunting noise he makes with the guitar, the hook that makes this song, which glitters across the surface passing through like the self-same waters of the title, reflecting sunshine. That sound somehow encapsulates a lot of the themes the whole album implicitly (and explicitly) plays with, hard flat desert sunlight, the feel of an epic landscape, stripped down and harsh, but lushly beautiful with fantastic colors. The geography they lived in and knew. Out of that this Arizona power trio concocted the studious country-inflected groove so familiar from their peak. Remember, the first album was a bit of a hardcore punk-rock exercise. So they covered a lot of ground to finally arrive at this quasi-Grateful Dead quasi-R.E.M. brooding style of feeling one's way through a jam, tightening it up and focusing it sharp. For the moment anyway they are verging on territory of acts such as Neil Young and the Band, tapping deep into veins of American experience in a way that's hard to explain. It's another absolute beauty.

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Casablanca (1942)

#9: Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942)

We've been at this for awhile and I'm tired, plus this one falls in the category of Everybody Already Said It. Therefore I'm going to take the easy way out and point to a review I wrote for my blog last spring. Maybe you can find something new in that. The short version: I've been watching Casablanca nearly all of my adult life, starting back when it was cut to pieces for commercial breaks on late-night broadcast TV, and I've been all over the map: in thrall to its screenplay, both at the level of the endlessly witty and quotable dialogue (the clip at the link is reasonably representative) and also at the level of its densely plotted structure ... and contemptuous of (or maybe I should dial that back to saddened by) its "of the times" racism and sexism. Mostly I have loved it. The last time I looked I liked it fine. I even thought I saw a way of looking at it that cleared up the sexism, maybe. People will be looking at Casablanca for as long as they remember Humphrey Bogart and World War II and the movies—that is, approximately until Cormac McCarthy's The Road becomes reality. Or, as the headline for a story about a Bogart retrospective we once ran in the college paper I worked at put it: "Here's kids looking at you, Bogey." Forever.

"I like to think that you killed a man—it's the romantic in me."

Casablanca review

Phil #9: On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) (scroll down)

Steven #9: A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951)

We've been at this for awhile and I'm tired, plus this one falls in the category of Everybody Already Said It. Therefore I'm going to take the easy way out and point to a review I wrote for my blog last spring. Maybe you can find something new in that. The short version: I've been watching Casablanca nearly all of my adult life, starting back when it was cut to pieces for commercial breaks on late-night broadcast TV, and I've been all over the map: in thrall to its screenplay, both at the level of the endlessly witty and quotable dialogue (the clip at the link is reasonably representative) and also at the level of its densely plotted structure ... and contemptuous of (or maybe I should dial that back to saddened by) its "of the times" racism and sexism. Mostly I have loved it. The last time I looked I liked it fine. I even thought I saw a way of looking at it that cleared up the sexism, maybe. People will be looking at Casablanca for as long as they remember Humphrey Bogart and World War II and the movies—that is, approximately until Cormac McCarthy's The Road becomes reality. Or, as the headline for a story about a Bogart retrospective we once ran in the college paper I worked at put it: "Here's kids looking at you, Bogey." Forever.

"I like to think that you killed a man—it's the romantic in me."

Casablanca review

Phil #9: On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) (scroll down)

Steven #9: A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951)

Sunday, November 11, 2012

The Turn of the Screw (1898)

I think there's a powerful undercurrent of the modern in this deceptive classic American horror story of and for children. I remember reading it for school at some point, I think in junior high (it couldn't have been easy!). But the more you look at the thing the more sophisticated and almost impenetrable it becomes. Perhaps the most modern part of it is the way it is actually the story, not of two children, or a possibly mad governess, or a haunted house and ghosts, but of a manuscript. The manuscript is in the possession of one "Douglas," who reads it for the entertainment of a gathering on a country outing, though none of them are ever heard from again once the governess' story, told in her manuscript, begins. At that level, of course, one soon loses all bearings, occupying the fevered brain of a frightened and/or hysterical young woman in her first real job, which she has taken (or claims to have taken) under unsettling circumstances and conditions. She sees ghosts. No one else does. She thinks the children do too. But that's not entirely clear. On the other hand, when the governess confides in the housekeeper about her experiences and describes the ghosts, strangers to her, the housekeeper recognizes them as people who have previously been involved with the children but are now dead. All this is gleaned from typical enough late James dense passages, a blizzard of intricate cross-hatching language with long tangled sentences in fat paragraphs that sprawl across most of a page, constantly qualifying anything that resembles a direct assertion. It is a kind of narrative optical illusion which looks like many things depending on how you look at it, but each with some flaw that throws the whole thing into ambiguity: A ghost story, except only one person seems to see the ghost. A woman coming undone but she's not the only one. At the end, she might even offer a flavor of the Jim Thompson psychopath, casually killing, but talking about it so elliptically you almost miss the horror show. And it's even possible here to see the children themselves as rageful aggressors, manifesting symptoms of sexual abuse. It's practically anything you want it to be and it's just a real corker.

"interlocutor" count = 3/97 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

"interlocutor" count = 3/97 pages

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

Saturday, November 10, 2012

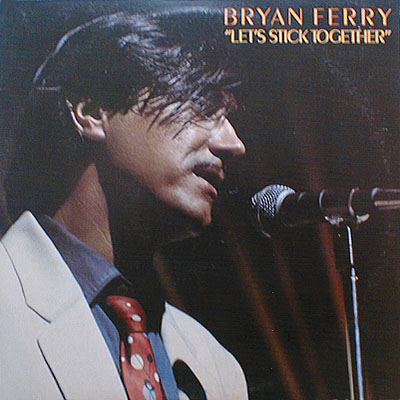

Let's Stick Together (1976)

This sounds pretty much like what it is, a grab bag of one-offs and B-sides from Bryan Ferry at an uncertain point in his career. It came right on the heels of the first dissolution of Roxy Music—it even seems to have half a foot still stuck back there, with alternate but not that different versions of "2HB," "Sea Breezes," and "Re-Make/Re-Model," all of whose originals appeared on the first Roxy Music album. There are also artifacts of the first phase of Bryan Ferry's solo career (as the crazy covers guy, personally my favorite of his many phases, followed closely by the Big Ripe Sigh of Avalon): "The Price of Love," an Everly Brothers song, "It's Only Love," a Beatles song, the standard "You Go to My Head." What saves this mess is the title song, which is also the first song and grabs hold tight right off the bat, in which Ferry is on the inspired attack with a scorching hot rhythm and blues band that is really something. I think the version here of "Let's Stick Together" stands up just fine to the Wilbert Harrison original or any of the other covers (by Canned Heat, Bob Dylan, Dwight Yoakam, George Thorogood, Nina Simone, etc., a number of big names). There's also a nice treatment of the Jimmy Reed song "Shame, Shame, Shame," full-on horns, harp, chick singers, whomping bottom, and needling guitar. So the essays in this direction do make the album worth checking out. Ferry would take it to some interesting places in at least one other solo, The Bride Stripped Bare, but I think its best expressions are found here. Still, in its totality the album is not that remarkable. The Roxy Music redos made and still make Ferry look a bit exhausted (if not desperate) on the ideas front. And I like the covers fine—as I say, I think especially These Foolish Things is terrific, on some days I'm even pretty sure it's the best thing he ever did in or out of Roxy Music. But these really sound like dregs and barrel scrapings, especially this second attempt at a Rubber Soul cover, which didn't even go that well the first time ("You Won't See Me," one of the few lowlights from that first solo). I wish I knew that next Bryan Ferry solo a little better, In Your Mind, because I know for sure by The Bride Stripped Bare he had some pretty interesting things going for him. Here it's limited to "Let's Stick Together," which is essential but quite possibly the only thing here that is.

Friday, November 09, 2012

Dogfight (1991)

USA, 94 minutes

Director: Nancy Savoca

Writer: Bob Comfort

Photography: Bobby Bukowski

Music: Mason Daring

Editor: John Tintori

Cast: Lili Taylor, River Phoenix, Richard Panebianco, Anthony Clark, Mitchell Whitfield, Holly Near, Elizabeth Daily, Sue Morales, Christina Mastin, Brendan Fraser

Dogfight is a small-scale romantic drama composed of many familiar elements and with a lot of courage and heart. Arguably it panders to baby boomer types such as myself already prone to lionize even the most insignificant parts of their lives with embarrassing sentimentality. When I finally noticed how much like Before Sunrise it is, the effect was to make me like Before Sunrise more—and to wonder how familiar Richard Linklater was with Dogfight and director Nancy Savoca's work generally when he made it, because the connections are there.

I have some sense now that Dogfight has faded into obscurity, which surprises me if only because of the River Phoenix performance. I see it discussed on the movie blogs I frequent only on rare occasions. It's missing entirely from my Halliwell's (the 2008 edition, which admittedly is a weird book). It made it to a DVD release in 2003, but that's now out of print (and commanding prices north of $100 for a new copy); yet there are no fewer than 80 customer reviews on its Amazon page. It occurs to me that what all this adds up to is Dogfight has become a cult picture and I am a member of the cult. So be it—here's hoping I can convince you to become a member too. Probably spoilers on the other side of the jump.

Director: Nancy Savoca

Writer: Bob Comfort

Photography: Bobby Bukowski

Music: Mason Daring

Editor: John Tintori

Cast: Lili Taylor, River Phoenix, Richard Panebianco, Anthony Clark, Mitchell Whitfield, Holly Near, Elizabeth Daily, Sue Morales, Christina Mastin, Brendan Fraser

Dogfight is a small-scale romantic drama composed of many familiar elements and with a lot of courage and heart. Arguably it panders to baby boomer types such as myself already prone to lionize even the most insignificant parts of their lives with embarrassing sentimentality. When I finally noticed how much like Before Sunrise it is, the effect was to make me like Before Sunrise more—and to wonder how familiar Richard Linklater was with Dogfight and director Nancy Savoca's work generally when he made it, because the connections are there.

I have some sense now that Dogfight has faded into obscurity, which surprises me if only because of the River Phoenix performance. I see it discussed on the movie blogs I frequent only on rare occasions. It's missing entirely from my Halliwell's (the 2008 edition, which admittedly is a weird book). It made it to a DVD release in 2003, but that's now out of print (and commanding prices north of $100 for a new copy); yet there are no fewer than 80 customer reviews on its Amazon page. It occurs to me that what all this adds up to is Dogfight has become a cult picture and I am a member of the cult. So be it—here's hoping I can convince you to become a member too. Probably spoilers on the other side of the jump.

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

Culture, "Black Starliner Must Come" (1977)

(listen)

This was never cut as a single, as far as I know, and on the album it's the seventh of 10 tracks, more or less buried on the second vinyl album side. But somehow it jumped out ahead of all the other songs for me on the seminal reggae album by Culture, Two Sevens Clash. It's charged with energy and clarity, bracing like a blast of oxygen to the face, bright and uptempo in its approach, as indeed the whole album is. It's also a pleasure to sing along with, with the clipped thud-thudding of some points of the phrasing counterpointing the lush and nimble pop song structure: "We are wait - ing on an op - por - tu -ni - ty ... For the Black Starliner shall come." The narrative elements are a confabulation of, first, the Black Star Line, which operated during 1919-1922, created by Marcus Garvey shortly after World War I, self-consciously modeled on the White Star Line, to facilitate goods traded among Africa and Africans throughout the world, and then second, the ongoing theme in Rastafarian culture about getting the fuck out of Babylon. The Garvey business I learned about just now digging around for some scraps of information about the song, but the second part I already knew, the yearning for liberation, as it is a theme that permeates the album as a whole, and it is a seminal reggae album for a reason. The song thus carries a heavy burden, but carries it lightly, setting a jaunty tempo from the start, studded with hooks and interesting features right along, such as that unique phrasing, the way it opens into the chorus, and the lulling chanting melody that keeps it sparkling. It's a real beauty.

This was never cut as a single, as far as I know, and on the album it's the seventh of 10 tracks, more or less buried on the second vinyl album side. But somehow it jumped out ahead of all the other songs for me on the seminal reggae album by Culture, Two Sevens Clash. It's charged with energy and clarity, bracing like a blast of oxygen to the face, bright and uptempo in its approach, as indeed the whole album is. It's also a pleasure to sing along with, with the clipped thud-thudding of some points of the phrasing counterpointing the lush and nimble pop song structure: "We are wait - ing on an op - por - tu -ni - ty ... For the Black Starliner shall come." The narrative elements are a confabulation of, first, the Black Star Line, which operated during 1919-1922, created by Marcus Garvey shortly after World War I, self-consciously modeled on the White Star Line, to facilitate goods traded among Africa and Africans throughout the world, and then second, the ongoing theme in Rastafarian culture about getting the fuck out of Babylon. The Garvey business I learned about just now digging around for some scraps of information about the song, but the second part I already knew, the yearning for liberation, as it is a theme that permeates the album as a whole, and it is a seminal reggae album for a reason. The song thus carries a heavy burden, but carries it lightly, setting a jaunty tempo from the start, studded with hooks and interesting features right along, such as that unique phrasing, the way it opens into the chorus, and the lulling chanting melody that keeps it sparkling. It's a real beauty.

Tuesday, November 06, 2012

North by Northwest (1959)

#10: North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959)

Alfred Hitchcock looms large for me as the film director who helped me understand what a film director is in the first place—I guess I used to think that a bunch of actors more or less got together and recited lines and, oh yeah, somebody must have brought a camera too. But I started figuring out how much more there was to it when I noticed that the episodes of the Hitchcock TV show actually directed by Hitchcock were noticeably better. (As a kid I was into the whole brand—watched the show, subscribed to the magazine, and read many of the books of stories, which is where I first encountered, among many others, Jerome Bixby's "It's a Good Life.") On the repertory theater circuit, the Hitchcock double features were always must-sees for me, most of them worth seeing again and again, simply because he was the director I could most rely on to deliver the engaging story that grabbed hold and didn't let go.

Later, in film classes and random reading, I came to better understand the kinds of deeper themes with which he was playing—the insinuations of paranoia and control in people's lives, the sly mockery of convention, and texturing it all with a disquieting, even creepy fear of women—alongside the clockwork technical aspects, which are most manifest in his gimmick movies, such as Rope, with its ostensible one long take (although you will notice that it does have a handful of old-fashioned cuts), or Rear Window, which is entirely set in a small studio apartment. I hasten to add that I count even his gimmick movies as worthwhile, sometimes even among his best, such as Rear Window (and also that it's probably possible to make an argument that all of his movies are gimmick movies).

Alfred Hitchcock looms large for me as the film director who helped me understand what a film director is in the first place—I guess I used to think that a bunch of actors more or less got together and recited lines and, oh yeah, somebody must have brought a camera too. But I started figuring out how much more there was to it when I noticed that the episodes of the Hitchcock TV show actually directed by Hitchcock were noticeably better. (As a kid I was into the whole brand—watched the show, subscribed to the magazine, and read many of the books of stories, which is where I first encountered, among many others, Jerome Bixby's "It's a Good Life.") On the repertory theater circuit, the Hitchcock double features were always must-sees for me, most of them worth seeing again and again, simply because he was the director I could most rely on to deliver the engaging story that grabbed hold and didn't let go.

Later, in film classes and random reading, I came to better understand the kinds of deeper themes with which he was playing—the insinuations of paranoia and control in people's lives, the sly mockery of convention, and texturing it all with a disquieting, even creepy fear of women—alongside the clockwork technical aspects, which are most manifest in his gimmick movies, such as Rope, with its ostensible one long take (although you will notice that it does have a handful of old-fashioned cuts), or Rear Window, which is entirely set in a small studio apartment. I hasten to add that I count even his gimmick movies as worthwhile, sometimes even among his best, such as Rear Window (and also that it's probably possible to make an argument that all of his movies are gimmick movies).

Monday, November 05, 2012

seenery

Movies/TV I saw last month...

About Schmidt (2002)—How did this one get away from me? Nicholson fatigue, I guess—I was dreading it from the DVD package. Much, much better than I expected.

The Bad Seed (1956)—The strain shows sometimes but mostly this is a great big kick, especially the ending so secret that the disclaimer is still appended not to say anything about it to anyone who hasn't seen it. So mum is the fucking word, believe you me. Recommended for October horror fests.

About Schmidt (2002)—How did this one get away from me? Nicholson fatigue, I guess—I was dreading it from the DVD package. Much, much better than I expected.

The Bad Seed (1956)—The strain shows sometimes but mostly this is a great big kick, especially the ending so secret that the disclaimer is still appended not to say anything about it to anyone who hasn't seen it. So mum is the fucking word, believe you me. Recommended for October horror fests.

Sunday, November 04, 2012

Essays of Elia/The Last Essays of Elia (1820-1825)

Together these two collections of essays by Charles Lamb, written over a five-year period for The London Magazine, amount to a little over 300 pages. They are not all that Lamb's reputation is staked on—his collaboration with his sister Mary on the children's book Tales From Shakespeare is at least as famous and may be even more beloved. But certainly his reputation as one of England's great essayists rests on these two slender volumes—slender even when they are combined into one. After Montaigne, Lamb remains one of the greatest writers of so-called "personal essays," exercises that at their best can be as rambling as they are engaging, and here it is basically on display at its very best. Lamb obviously dwelt happily upon his responsibilities as a magazine columnist, applying himself with zeal and diligence to topics such as New Year's Eve, Valentine's Day, roast pork, memories of schooldays, odd people he has met, and adventures at the theater. Lamb first came to my attention for the essay "Dream-Children: A Reverie," which is lovely and bittersweet, a unique view of a man who made his career as an author of children's books but never had any children himself, dipping into dreams of what might have been, and somehow, in artful fashion, finding an extraordinary way to take us there with him. It's beautiful, and to be honest, I did not find it bettered by anything else here. But if you don't know "Dream-Children" I envy you the opportunity to encounter it for the first time, along with some 40 or 50 other pieces by Lamb, all of them worth the time at least once. He's a genuine eccentric, often elliptical and clipped in strange ways, further obfuscated by the dense elocutions of the first half of the 19th century. It takes some getting used to, and some patience. What I like best is the sense of liberation, the idea that the essay writer can do and write anything. That all started with Montaigne, of course, who is undeniable. Somehow there's something more personable for me in Lamb, all packed away neatly and helter skelter in the little Elia books.

In case it's not at the library. (Project Gutenberg)

In case it's not at the library. (Project Gutenberg)

Saturday, November 03, 2012

Live/Dead (1969)

As for the Grateful Dead, I have circled back on myself so many times I'm not even sure exactly where to pick up the thread. But I can say at least at long last I have the decency to recognize this album for the powerful, stirring, and mysterious set that it can be—notably, "Dark Star," the 23-minute opener that occupied the first side of the vinyl double-LP and periodically reenters and rules my world again, often after dark in quiet rooms alone. Candles burning, etc. More recently, "Death Don't Have No Mercy" and the eight-minute feedback sculpture (capped by the tremblingly beautiful but very brief "And We Bid You Goodnight"), which occupied the fourth side, have emerged as stellar points in their own right. "St. Stephen" and "The Eleven," side 2, at one time were my favorites, along with similar passages from Anthem of the Sun. That leaves only the 15-minute Pigpen goof made out of "Turn on Your Love Light" left for me to make peace with (which, to be honest, would not seem to be coming any time soon as it still seems to me indulgent and unnecessary, though I know Pigpen has his partisans). "Dark Star" remains my chief way in here, truly one of the great album sides along with Bitches Brew side 1 ("Pharoah's Dance") or Electric Ladyland side 3. Partly for such reasons I was tickled to find a "single version" of "Dark Star" on the expanded version of this album now available—that such a thing would exist never occurred to me. But sure enough, there are all the singing parts polished and marshaled in a row, with even some flavor of the guitar breaks scattered in lightly, tidying up at a relatively scant 2:42. Interesting to hear it conceived that way, because I so much prefer what is done with the longer version, which feels its way into the many strange places it travels. It's a jam but not what I think is more often implied by the term, a sort of communal rocking out with turns at solos. Instead it operates almost like pure intuition, mimicking and anticipating daydreamy kinds of thought patterns in endlessly eerie ways. It's even hard for me to focus on it as music once it starts to play; it is much more like a place I move through, or that moves past me, familiar but never quite known. I lose my concentration somehow, as it produces a sensation of returning to a city long abandoned, but whose streets and sites I still know well, embedded into neural pathways out of the reach of consciousness. I know where it's going, I sense the turns even as they approach, I never feel lost, and yet it is always beautiful in ways I can't anticipate. It still surprises me.

Friday, November 02, 2012

3:10 to Yuma (2007)

USA, 122 minutes

Director: James Mangold

Writers: Halsted Welles, Michael Brandt, Derek Haas, Elmore Leonard

Photography: Phedon Papamichael

Music: Marco Beltrami

Editor: Michael McCusker

Cast: Russell Crowe, Christian Bale, Logan Lerman, Dallas Roberts, Ben Foster, Peter Fonda, Alan Tudyk, Gretchen Mol, Kevin Durand, Luke Wilson

It must be said first, I think, that there's a lot of pure competence on display in this latter-day remake of the classic '50s Western, right down to screenplay, performances, editing—even folio work. I was surprised by how compelling it can be and by how well it sustains that, having brought low expectations with me to yet another Hollywood recombinant DNA project. But it's also light on inspiration, signaled most obviously by the fact that it's a remake, which if not a fatal flaw nonetheless remains a burr in the saddle.

Based on an Elmore Leonard short story from 1953 (published originally in "Dime Western Magazine"), the story is a finely tuned instrument: a desperately impoverished rancher volunteers to join a militia delivering a very bad man to a train (the 3:10 to Yuma of the title), which will forward the very bad man on to prison. But the very bad man's gang, possessed of prodigious abilities, wants to prevent this from happening. The tension is established early and never really lets up, even as the ending enters into bizarre and unbelievable realms with various narrative problems.

Director: James Mangold

Writers: Halsted Welles, Michael Brandt, Derek Haas, Elmore Leonard

Photography: Phedon Papamichael

Music: Marco Beltrami

Editor: Michael McCusker

Cast: Russell Crowe, Christian Bale, Logan Lerman, Dallas Roberts, Ben Foster, Peter Fonda, Alan Tudyk, Gretchen Mol, Kevin Durand, Luke Wilson

It must be said first, I think, that there's a lot of pure competence on display in this latter-day remake of the classic '50s Western, right down to screenplay, performances, editing—even folio work. I was surprised by how compelling it can be and by how well it sustains that, having brought low expectations with me to yet another Hollywood recombinant DNA project. But it's also light on inspiration, signaled most obviously by the fact that it's a remake, which if not a fatal flaw nonetheless remains a burr in the saddle.

Based on an Elmore Leonard short story from 1953 (published originally in "Dime Western Magazine"), the story is a finely tuned instrument: a desperately impoverished rancher volunteers to join a militia delivering a very bad man to a train (the 3:10 to Yuma of the title), which will forward the very bad man on to prison. But the very bad man's gang, possessed of prodigious abilities, wants to prevent this from happening. The tension is established early and never really lets up, even as the ending enters into bizarre and unbelievable realms with various narrative problems.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)